![]() You don't need to be an 'investor' to invest in Singletrack: 6 days left: 95% of target - Find out more

You don't need to be an 'investor' to invest in Singletrack: 6 days left: 95% of target - Find out more

I’ve got a degree in Aeronautical Engineering, I’ll survive.

Perfect a then dive straight into the more “university lecture” stuff.

Once up to speed the force is zero.

Apart from the camshaft the valve train is rarely at constant speed - is is continually accelerating in one direction and then the other to drive the valve from its static “closed” position to moving quickly toward “open” and then decelerating to achieve its “open” position, then the reverse to close.

So you’re saying mass has a direct influence on the force needed for a given accelaration?

Yes. Apologies for the overly simple explanation earlier. Basically F=m.a

Well yes but that doesn’t help the case for pushrods though. The only reason they still have pushrods are because they have to. They also have to have carburettors too.

Nascar engines use electronic fuel injection.

The point about Nascar engines is that pushrod engines can rev much harder than people assume and can generate pretty decent horsepower.

The point about NASCAR engines is they have been developed within a prescribed et of parameters.

Push rods are shit and belong in the dark ages outside of industrial applications. It's operationally advantageous to be able to pull a cylinder head at sea with nothing more than a windy gun and a chain block, you pay for that in energy losses. Only medium speed engines use push rods last I checked since slow speed are entirely electronic and high speed use camshafts and belts.

high speed use camshafts and belts.

I think you'll find proper race engines use gear drives, not timing belts or chains. Timing belts are cheap and quiet, but aren't up to the demands of proper high-performance engines.

The 1994 Indy 500 was won by a car with a pushrod engine, build buy Ilmor and funded by Mercedes-Benz.

Exploiting a loophole that allowed 3.4 litre pushrod engines to run higher boost than their 2.6 litre competitors, right?

Exploiting a loophole that allowed 3.4 litre pushrod engines to run higher boost than their 2.6 litre competitors, right?

Yes. It happened because they allowed stock-block engines with pushrods as a cheaper alternative to custom built race engines. Buick V6s were pretty common back in the 80s, but weren't reliable because of the requirement to use stock parts. The stock parts requirement was lifted to help the Buick based engines. When Ilmor realized that the requirement for stock part had been removed, they built a custom engine to take advantage.

My point isn't that pushrods perform as well as DOHC for racing engines, it's that the idea that pushrod engines are "shit" isn't quite right. They can rev a lot harder and put out more power than people often assume and the Chevy small-block engines seem to go pretty well. In the Australian V8 touring cars, the quad-cam engines struggled against the Nascar based pushrod engines because they were all rev limited to 7500 RPM and had limitations on camshafts to prevent an expensive engine development arms race. There was no power advantage to quad-cam engines under those regulations, but they used more fuel. The rules were relaxed a few years ago to allow turbo V6 engines in. GM built a quad-cam V6 turbo, but never raced it.

This really is peak STW. Some dude who clearly knows about this stuff shows up and answers the OP's question, then a bunch of other people show up and try and pick holes in the explanation.

Love it.

I think you’ll find proper race engines use gear drives,

If you put your part quote back. In context SK is clearly talking about industrial/boat applications as is his vocation.

Main reason that we don't use gear drives and pushrods outside of the racing world is that over the years we have grown to enjoy not driving with ear defenders on.

The point about Nascar engines is that pushrod engines can rev much harder than people assume and can generate pretty decent horsepower.

Yes I acknowledged that but the point was it’s not a valid example because it’s not the optimal solution. Free from the restriction of the rules of the game the engine designers would ditch pushrods and have a more technically optimal design.

NASCAR is steeped in history and nostalgia which is hampering the innovation in the sport and channeling it into a single technical solution which they’re doing their best to ring the next out of.

The future is camless and pneumatically actuated.

Why pneumatic specifically? Is it a speed thing?

Don’t know. It’s what F1 engines use and the Kenisegg that has a cam less valve train. I guess hydraulics would be too heavy and I think the compressibility of air might be a factor.

Still no answer as to why push rod engines intrinsically have better bottom end power @trail_rat

There are/were plenty of 2 valve OHC engines as anyone who drove an early 90s Sierra or Escort would attest.

Obviously there are some cam profile and rpm limits to push rod engines without spending a lot of money on them so at a disadvantage over OHC. If you wanted a fatter bottom end on an OHC engine there is nothing stopping you having smaller valves and less overlap to get this (you could do this with pushrod too). You can also have bigger valves with more overlap and use higher revs, harder to do with a push rod engine.

Force on the pushrod will go up with engine speed and how steep the opening profile of the cam lobe is. You effectively have a small (on a car engine) tube in compression so its not an ideal engineering solution if you want aggressive cams and lots of revs.

Still no answer as to why push rod engines intrinsically have better bottom end power @trail_rat

I said good not better. Good by virtue of the missing top end.... If they were all mega bucks race engines with exotic internals and could have a full rev range then the statement would be .... Good range

And you hit the crux of the whole matter.

Ohc engines are easier to tune to the characteristics you desire instead of living with compromises.

I said good not better. Good by virtue of the missing top end…. If they were all mega bucks race engines with exotic internals and could have a full rev range then the statement would be …. Good range

But there were also a lot of race escort engines running big valves and aggressive cams with lots of overlap that don't have a great bottom end too.

Basically there is nothing about a push rod engine that intrinsically ensures a good bottom end. In fact if you take most push rod engines that were main stream in the UK they didn't have power anywhere 🙂

I am not trying to give you a hard time, just trying to make sure people understand and don't perpetuate myths.

Why are we still arguing about who has a better rock that their dads gave them to smash a nut, when there are nut crackers.

That is really easy to answer. See my first post for the main points. But… specifically relating to the valves and cams it goes like this.

I know the limitations of pushrod engines. I've got one in my 2nd car, and it's no longer possible to get properly hardened camshafts for it which makes the weaknesses accutely apparent when ever you measure the valve clearances.

My point was specifically related to diesels. Which neither rev as quickly, nor rely so much on scavenging and the effects of momentum on the intake to the same extent due to forced induction. Even what Google suggests is the sportiest diesel (Audi S4 apparently) hits peak power (not torque, power) at 4000 rpm which is nowhere near troubling a pushrod.

Pushrods, for all their limitations, would appear to be good enough that they could have been used (and were in some cases). The reason for their dissaperance seems much more to do with subsequent diesels being derived from petrol blocks and diesels popularity not really surging untill those petrol engines moving over to OHC layouts.

Pushrods, for all their limitations, would appear to be good enough that they could have been used (and were in some cases).

Good enough is no longer good enough. In Europe where we've not been building huge inefficient engine for decades, the push for more efficient engines had pushed manufacturers to build better and more efficient engines. Pushrods were one of the first things to go. The US has lagged behind that efficiency curve...they just solved the issue of power and torque by adding CC's - hence much larger engines and the need for Lower profile cylinder heads - a kind of self fulfilling prophecy. The Europeans had no such luxury. And the influence on F1 vs NASCAR also helps. Europeans like peaky, reviver engines for the narrow and twisty mountain roads or country lanes, the yanks like to lollop along the freeway at 60mph with a big lazy V8 up front ticking over at 750 rpm and getting about 10mpg...but who gives a toss when fuel is cheaper than water.

The reason for their dissaperance seems much more to do with subsequent diesels being derived from petrol blocks and diesels popularity not really surging untill those petrol engines moving over to OHC layouts.

Well that and just simply better performance overall..what are the downsides to OHC? You say that as if production efficiency, supply chain efficiency, scaleable designs that can be used for many applications is not an important factor for an engine producer and that it is a bad thing. It's already been confirmed by someone who does this for a living that pushrod engines, for cars at least, are limiting in design and performance, expensive to produce, have additional parts count and complexity and hamper design options. Again....exactly what are the benefits to pushrod engines apart from nostalgia and harking back to yesteryear? it is old tech and like any old tech, apart from the odd niche application, it's been superseded by better technology.

I would say its cost the main reason not used in pretty much any engine these days.

OHC engines are cheaper to build now, would be my guess.

Pushrods, for all their limitations, would appear to be good enough that they could have been used

Pushrods are NOT “good enough” for modern diesels, hence why they’ve now been replaced in the vast majority of cases.

peak power (not torque, power) at 4000 rpm which is nowhere near troubling a pushrod.

If peak power is at 4000 rpm redline is likely circa 4,500 and the max over speed condition designed for will likely be a bit over 5,000.

Pushrods don’t have a max rpm limit as such, it’s just that they’re overall higher mass hence limits are more challenging and you have to make greater design compromises in other areas (valve motion) to allow for this, which hurts performance and emissions.

Although a diesel doesn’t rev to the same high rpm as a petrol it’s still fast enough for the valvetrain dynamics to be a limiting factor, so a lighter valvetrain allows for better performance and emissions.

For comparison the 1500 and 1800RPM Diesel and Natural has engines we develop at work are still valvetrain dynamics limited and we design around these operating speeds and then work backwards to optimise valve motion (I.e. cam profiles) to the force limits that result from this operation. If we could use OHC on those we would ease these restrictions further and be able to have more freedom in cam profile design (we can’t because our engines need pushrods for the reasons I have in my first post)

Any technology has to 'win' its way onto any product. It has to demonstrate its contribution to achieving the overall specification that drives the design. If there are no net benefits that satisfy all of the design specification then it doesn't make its way onto a product. Its as simple as that.

Peoples perception that engineers design the products they want to design is not true. They engineer the products that the market wants and is driven by very specific parameters driven by market desires (looks, performance, cost to buy and maintain, reliability etc), economics of production, and more and more dominating these days are political and regulatory requirements. So with all these competing requirements any technology that can't justify its inclusion by ticking all of these boxes has no right to be selected....hence the death of pushrods and many other technologies over the years. And some technologies have made a revival due to a change in the requirements...like turbo's, electric motors (Porsche were messing around with electric hybrid cars 100 years ago) and even Diesel engines themselves.

No engineer set out with the mindset of "I'm going to design a pushrod engine". They set out with an aim to design an engine that is small, light, can be manufactured for £x per unit, can achieve x bhp and y NM of torque, achieve z l/km economy, have a service life of x years and cost x per year to maintain and will meet all the noise and emissions regulations.....the technologies to achieve all of that are then selected. How are pushrods contributing to all those requirements vs OHV or any other technology...the first question might be is an internal combustion engine the right powerplant in the first place?

Still no answer as to why push rod engines intrinsically have better bottom end power @trail_rat

acknowledging that trail rat meant “good” not “better” and the others have already responded to this. My view is that…

Pushrod engines do not have better low end power.

2 valve heads generally have better low end power than 4v (generalisation). This is due to gas flow dynamics in the intake port, valve and heads.

sanity to the thread

thank you

so, do I have this right -

at any design target RPM for any engine type, the ideal valve movement is always "as fast as possible" and as pushrods are not faster than OHC, pushrods mean always suboptimal efficiency/power

then, all that, traded off against simplicity / ease of service / packaging (e.g. that new BMW boxer) / marketing (harleys, GM v8)

+1 for @wobbliscott ‘S answer.

Most engines are developments and derivatives of previous designs, but when there’s a large scale new design or clean sheet design the most experienced group of engineers will spend time determining the overall architecture. That’s how things like the newer smaller 3 cycl 1 litre turbo engines have come into being - technology has advanced enough that when a clean sheet design is made these are now feasible.

the first question might be is an internal combustion engine the right powerplant in the first place?

Absolutely correct - there are now feasible options to IC engines and rapid progress is happening, hence all of the various hybrid and electric options becoming available.

@mrmonkfinger - thanks, I hope these replied are interesting / useful and not coming across as a bit lecture / I know better ish.

at any design target RPM for any engine type, the ideal valve movement is always “as fast as possible”

Correct. This is of course a generalization but the optimal opening / closing speed is generally faster than valve & cam technology allows for.

and as pushrods are not faster than OHC, pushrods mean always suboptimal efficiency/power

Pretty much. Pushrods generate higher forces for a given valve motion and speed, hence the achievable speed limit would be lower for the same valve design and speed. It is not acceptable to have engines overly low RPM limits, and also not acceptable to have engines which fail or have short lives hence the part of the design that gets compromised is the valve motion.

You can also throw a lot of money at making the valvetrain lighter - carbon fibre / titanium pushdrods, exotic valves etc which helps but adds $$$

then, all that, traded off against simplicity / ease of service / packaging (e.g. that new BMW boxer) / marketing (harleys, GM v8)

Correct, it's a trade-off as is all good engineering design.

Re tradeoffs Harleys for example have a massively compromised design to allow for marketing. Their twins fire at 90 degrees offset, not 180 to give that Harley sound and lumpiness. But that fault feature is WHY people buy harleys.

STW is not Michael Gove, we like experts 🙂

Pushrod engines do not have better low end power.

2 valve heads generally have better low end power than 4v (generalisation). This is due to gas flow dynamics in the intake port, valve and heads.

Yes. In principle, you could take a pushrod engine and build an OHC cylinder head with exactly the same arrangement of ports, combustion chamber, cam profile, etc., the only difference being how the valve actuation was done. In that case, you would expect pretty much the same power curve, the only difference would be the friction in the valvetrain. A thought experiment like that shows that there is nothing inherent in pushrods that give better low down torque.

Toyota and Honda looked at turbocharging versus multi-valve OHC back in the 80s. They apparently came to the conclusion that DOHC was optimal for road cars. That would have considered cost, reliability, fuel economy, emissions, etc. Toyota started out with wide-angle high-performance cylinder heads, but they were expensive to produce so they used a cheaper narrow-angle design for standard cars. The high-performance versions were designed to rev hard and produce high power at high revs. The standard engines were designed to produce good drivability and economy. The torque curve of the engine isn't directly due to whether it's OHC or not, you could make a DOHC engine with massive low-down torque and not a lot of top-end power if you wanted to. A lot of those compromises are reduced now with variable length intake manifolds and variable valve timing, so you get a much wider usable power band.

all that, traded off against simplicity / ease of service / packaging (e.g. that new BMW boxer) / marketing (harleys, GM v8)

GM had a quad-cam V8 but dropped it in favour of a clean-sheet pushrod engine. That had nothing to do with marketing. They did their sums and decided that pushrods were a better solution for that particular situation. The current Chevy V8s use variable intake manifolds, variable valve timing, and direct injection. They rev to a bit over 6000 RPM and crank out over 400 HP. That's about double the power output of what they were getting out of the old V8 designs in the 90s. It obviously wasn't the pushrods that limited the old engines, it was the design of the intake and exhaust manifolds, porting, combustion chambers, and injection systems. Once those were modernized, the engines suddenly started putting out decent horsepower.

Yes. In principle, you could take a pushrod engine and build an OHC cylinder head with exactly the same arrangement of ports, combustion chamber, cam profile, etc., the only difference being how the valve actuation was done. In that case, you would expect pretty much the same power curve, the only difference would be the friction in the valvetrain. A thought experiment like that shows that there is nothing inherent in pushrods that give better low down torque.

I agree with all of this, except to add that in addition to friction in the valvetrain the mass would rise, hence inertia and highly likely that after extended running you'd be more prone to getting premature wear and failures due to higher forces (cam surface wear and cracking etc). Also likely no-follow conditions between the pushrod / follower and cam lobe. Ignore these and the short-term performance would be pretty much identical.

To avoid these circumstances you'd have to back off and "soften" the cam profiles, the result would be a reduction in performance, efficiency and an increase in emissions.

It obviously wasn’t the pushrods that limited the old engines, it was the design of the intake and exhaust manifolds, porting, combustion chambers, and injection systems.

I agree. The pushrod system is just one of many factors in a design. They are perhaps unfairly seen as very limited as they tend to be associated with old designs where the overall engine performance is poor as a result of all of these different factors and the poor pushrod gets associated with all of that. Design a modern engine around a pushrod system and you both get the benefit of all the modern technologies but also get to optimize the design for the pushrods limitations, so you can take advantage of it's plus points (package size and simplicity of drive for a V8) whilst designing around its limitations (valvetrain inertia).

Same with the pushrods valvetrains we use in our industrial engines. They're overall very high tech, and we design around the limitations, just like we do every other limit that exists in an engine (the there are hundreds if not thousands of limits and compromises involved in an engine design).

That had nothing to do with marketing

I dunno. It might have had something to do with marketing - smaller engine, mounted lower & further back, used in sports car, etc etc. I did google that the motor was about $400 less to produce using pushrods vs OHC & belts. That aside, some of those old US V8 engines had woeful gas flow, as you say, and probably not that difficult to improve on.

BTW do we need to start another thread, 'why are there no sleeve valve engines' ?

I teach A level physics for a living

On one of our worksheets students estimate the acceleration of a piston in an engine. The bright students students always get embarrassed and ask where they've gone wrong when they get 20,000 m/s^2. I think the stroke length is probably a bit long but it makes a useful point.

Using a stick to poke a valve open once is easy. Doing it 2000 times a minute, each time as quickly as possible, and the sticks inertia really matters.

Great thread I've learnt loads

To avoid these circumstances you’d have to back off and “soften” the cam profiles, the result would be a reduction in performance, efficiency and an increase in emissions.

No, the thought experiment was to take an existing pushrod engine and convert it to OHC with identical ports, chamber, and cam. The cam profile is already suitable for a pushrod engine.

Thing is that older road car engines had pretty mild cam profiles, regardless of whether they were pushrod or OHC. Manufacturers weren't putting the lumpiest possible cam in anyway, hence pretty much any stock engine could be improved just by getting the cam reground, rejetting the carburettor or remapping the injection, and tidying up the intake and exhaust. Often, the limitation on camshaft lift was to prevent the pistons striking the valves if the timing chain broke. It was nothing to do with the mechanical limitations of pushrods or OCH valvetrains.

I think the thing that the people trying to pick holes in markwsf's answers are not getting is the fact that, even if push rods could feasibly do the job, that alone is not good enough. For the automotive market, manufacturers are pushing to the very limit of what is possible with existing technology in order to meet emissions targets. Taking a step back to push rods simply isn't possible whilst maintaining those targets, for the reasons markwsf described. Soon manufacturers will have to design to meet euro 7 and I suspect a lot of them are quite worried how they're going to achieve that even without stepping backwards in technology.

The LS series engines are a corner case that simply isn't relevant to the majority of UK sales. Most cars sold here come under a portfolio that has to collectively meet fleet emissions regulations and you can't have a sub-optimal solution needlessly dragging that figure down.

On one of our worksheets students estimate the acceleration of a piston in an engine.

Does it take account of the conrod length? The shorter the conrod relative to the stroke, the higher the piston acceleration. A shorter rod will improve low-end torque, but cause higher side loading on the pistons. A longer rod will need a higher deck height, which will make the engine heavier and taller (or wider in the case of vee engines).

https://www.enginebuildermag.com/2016/08/understanding-rod-ratios/

Using a stick to poke a valve open once is easy. Doing it 2000 times a minute, each time as quickly as possible, and the sticks inertia really matters.

Yes. Look up "high speed valve spring" or similar on youtube for some cool vids!

The bit that still amazes me is that not only do the valves open and close that fast, but there is a carefully designed closing ramp so they don't get "slammed shut", but slowed down so the actual velocity at closure is quite low - to avoid multiple issues but mainly valve recession (wear of the valve/seat interface). We use software these days that takes into account the inertia of all the components etc but it just comes down to basic differentiation and integration of curves.

the thought experiment was to take an existing pushrod engine and convert it to OHC with identical ports, chamber, and cam. The cam profile is already suitable for a pushrod engine.

Oh, I see. Yes, this way around would work fine and the performance would be pretty much identical bar a slight frictional difference which would be lost in the noise anyway.

Often, the limitation on camshaft lift was to prevent the pistons striking the valves if the timing chain broke. It was nothing to do with the mechanical limitations of pushrods or OCH valvetrains.

Agree. The tools that are used to design and simulate these systems didn't exist back in the day so there was a lot more trial and error which lead to more conservative designs. They'd push harder until issues were apparent and then try and engineer the issue out - which leads to improved materials, designs, calculation and analysis etc added to more experience hence progress. Still the same iterative process today just with more computational power.

Interestingly, when diving into these topics WW2 aircraft engines are very often a major topic as the sudden need for development of increased power and longevity drove a vast range of improvements. For example the valve seat materials used on high performance engines (Stellite and other cobalt based alloys) came into use (in engines) in this period and are still one of the premium choices now.

@rsl1 - thank you, you've summarized it much better than me.

Even if the use of pushrods for mainstream automotive applications is/was "possible" it's not the optimal solution so would not get used. As you say every design choice is very stringently chosen to be the best available and 99+% of the time OHC represents the best choice - it's such a clear choice that its not a decision that takes long to make. Which is important as that decision making effort needs to go into other areas that do offer genuine choice.

For example - what flavor of variable valve timing / lift is optimal etc. That's a complex subject and there is not "right" answer - each company has it's own preference & often proprietary systems and even they don't apply the same system each time.

Now add hybridization onto it and even the use of the Otto or Diesel cycles themselves gets challenged, with a lot of hybrids opting to use the he Atkinson cycle engine instead (for turbocharged industrial engines we often use the Miller cycle, which is closely related).

Why are we still arguing about who has a better rock that their dads gave them to smash a nut, when there are nut crackers.

If you're talking about the shift to EVs then yes, it's remarkable how almost this entire debate will be completely irrelevant in a decade or less, and the only people who know anything about it will be specialists designing for the remaining niche applications for ICEs. Just like all the stress over the condition of the various transmission and engine components in my Merc (see thread) or the black smoking issue on someone's Nissan (see other thread). It'll all go away.

Re pushrods specifically in diesels - isn't the instant force at detonation significantly higher in a diesel? Wouldn't that result on greater shock loading on the pushrod, cams and rockers and hence require more heavily built parts and exacerbate the problem more than on a petrol engine?

Although a diesel doesn’t rev to the same high rpm as a petrol it’s still fast enough for the valvetrain dynamics to be a limiting factor

Except that is the bit which is demonstrably false.

The final(ish, it went on a lot longer in various guises) iteration of the BMC A-series in the Mini Copper S didn't hit it's peak until 5900rpm. And that was with the big (thus heavier) 2-valve head. 4 valves and 16 pushrods would each weigh less (or you could go down a development path of wider cams and elliptical followers to spread the load, etc)

And the question was never phrased "why are there no new...." or "could you build a euro7.....". It was why did they not persist a lot longer than they did. And I'm just not convinced cam profiles and rev limits explain it.

Now add hybridization onto it and even the use of the Otto or Diesel cycles themselves gets challenged, with a lot of hybrids opting to use the he Atkinson cycle engine instead (for turbocharged industrial engines we often use the Miller cycle, which is closely related).

Mazda use miller cycle engines in their non hybrids. Hence why They've gone down a path of really low specific output compared to everyone else.

isn’t the instant force at detonation significantly higher in a diesel?

Happily not as during combustion the valve is closed and so the combustion forces are reacted through the valve seat and cyl head. If the valves are open during combustion you've got a whole different problem !

Although a diesel doesn’t rev to the same high rpm as a petrol it’s still fast enough for the valvetrain dynamics to be a limiting factor

Except that is the bit which is demonstrably false.

It really isn't - see below.

The final(ish, it went on a lot longer in various guises) iteration of the BMC A-series in the Mini Copper S didn’t hit it’s peak until 5900rpm. And that was with the big (thus heavier) 2-valve head.

Yes, you can design a pushrod engine to achieve high RPM. The use of pushrods at high RPM will just impose significant compromises on things such as the achievable valve speeds which matters massively for emissions and efficiency.

If you're happy with BMC A series levels of performance then sure, why not.

And I’m just not convinced cam profiles and rev limits explain it.

Bearing in mind that this field is what I do for a living, and if after everything I've written in this thread you still think that then I'm not going to bother trying to explain any more as you're either not reading, taking the time to think this through, not believing me or are trolling.

there is a carefully designed closing ramp so they don’t get “slammed shut”, but slowed down so the actual velocity at closure is quite low

IMHO, this is one of the key limitations inherent in pushrod operated valves - the cam can only control valve closing while all parts of the valve train remain in contact with each other. If you increase the speed of the engine there comes a point where the inertial loads in the valve train cause some of its components to lose contact on the cam closing side. The valve is then free to accelerate until it slams into its seat causing rapid wear / mechanical failure. It can also happen that the floating valve doesn't close in time to avoid the rising piston - especially important for diesel engines with their high compression ratio / small piston to valve clearance.

To echo Markwsf - there's no intrinsic characteristic of pushrod vs OHC that affects power delivery, other than pushrod valvetrains inherently have more inertia than OHC type valvetrains which either limits RPM for a given valve lift curve, or enforces a more conservative valve lift curve to achieve a given RPM.

The power delivery of an engine can be tuned to whatever is required within these restrictions.

Other reasons for the demise of pushrod engines: "manufacturability" - OHC designs generally have lower parts count and are more suited to automated assembly; Efficiency - lower valve train inertia for OHC can be exploited to offer better power to weight for a given reliability or reduced fuel consumption for a given power output; Noise - there are fewer mechanical interfaces in an OHC design, so fewer noise sources, and they all tend to be concentrated in one place.

Now then, why aren't there more side valve engines? 😀

@molgrips - apologies I didn't quote the full piece of your post that I meant to and too late to edit - please disregard and I'll re-post below

isn’t the instant force at detonation significantly higher in a diesel? Wouldn’t that result on greater shock loading on the pushrod, cams and rockers

Yes, the actual instantaneous pressure is (generally) higher - plus Diesels run higher CR's so the pressures are higher anyway. Happily this force is not transmitted through the valvetrain as during combustion the valve is closed and so the combustion forces are reacted through the valve seat and cyl head. If the valves are open during combustion you’ve got a whole different problem !

The whole structure of a Diesel does generally need to be able to survive higher pressures though - so blocks, heads, valve heads, pistons, con-rods, cranks etc are all usually larger & heavier. Clearly there are exceptions to this for various reasons but as a general trend it's true.

This is a good thread. 🙂

If the valves are open during combustion you’ve got a whole different problem !

On that cylinder, yes - but what about the others? In a 4cyl isn't one exhaust valve opening whilst combustion is happening on another?

I do find engine design fascinating but I can't wait for the time when they aren't on our roads.

On that cylinder, yes – but what about the others? In a 4cyl isn’t one exhaust valve opening whilst combustion is happening on another?

The valves should only be opening and closing when there is fairly low pressure in the cylinder.

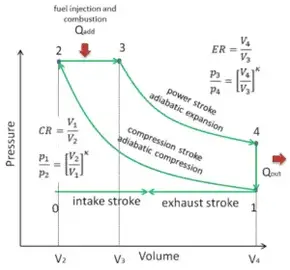

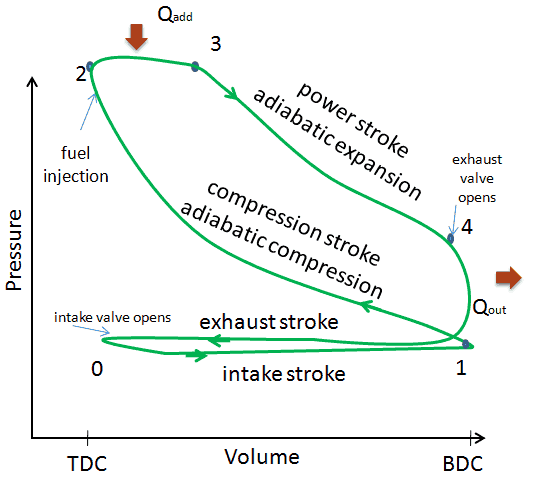

In the "ideal" Diesel cycle as per the PV diagram below that's exactly at bottom dead centre, and all of the gases instantaneously disappear out of the cylinder.

The reality is that there is a finite time for the valve to open, and a finite amount of time for the gases to leave the cylinder, during which time the piston is still moving (one of the reasons for the "open and close valves as fast as possible" goal).

So there will be some pressure against which the valve has to open, but nowhere near full combustion pressure.

For comparison a "real" PV diagram looks more like this

One of the goals in IC engine design is to get the real-world PV diagram as close to the ideal one as possible, as all of those "missing corners" represent energy that's being lost.

I do find engine design fascinating but I can’t wait for the time when they aren’t on our roads.

I fully agree. In the long term the engineering skills are all transferrable, and in the short-medium term there is actually a lot MORE engine development going on as the demands on engines are changing rapidly, from being the only source of power to being part of a more complex system.

One simple example is turbo lag. It used to be a really big deal, and compromises were made to minimise it. With advent of hybrids an electric motor can pick up the load instantly, so turbo lag is much less of an issue, hence the system can be better optimised for efficiency, power and emissions.

I do find engine design fascinating but I can’t wait for the time when they aren’t on our roads.

Even if they're running on Hydrogen? If you mean you cant wait for a time until there are no cars on the roads full stop, then it will be a cold day in hell till that happens. But if its from an oil burning environmental point of view then Hydrogen is well and truly in the future of cars...either in the form of Hydrogen fuel cells or hydrogen burning ICE's. BEV's are not going to do it for everyone.

In a 4cyl isn’t one exhaust valve opening whilst combustion is happening on another?

A 4 cylinder crankshaft looks like this.

Cylinder 1 and 4 are 360 degrees apart (a complete 4-stroke cycle is 720 degrees, with 1 stroke taking 180 degrees of crankshaft revolution). Cylinders 3 and 2 are 180 and 540 degrees behind cylinder 1. When cylinder 1 is on its firing stroke (both valves closed), cylinder 4 is on its intake stroke (intake valve open), cylinder 3 is on its exhaust stroke (exhaust valve open), and cylinder 2 is on its compression stroke (both valves closed). It's not quite as simple as that because there is overlap between the intake and exhaust valves, so the intake valve starts to open before the exhaust valve is fully closed.

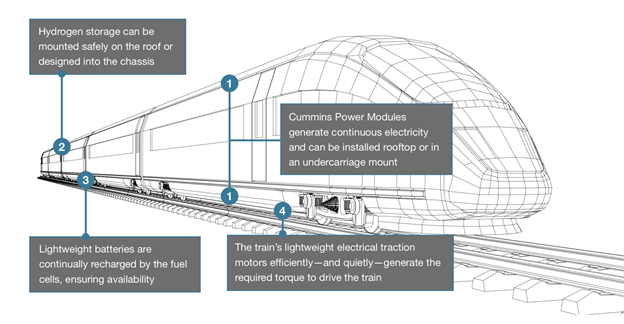

Re Hydrogen.

For all-day use type applications batteries won't cut it in the near future, so Hydrogen is being actively developed, both as an alternative fuels to use in developments of existing engines and also for fuel cells.

Of course, this relies on producing the hydrogen without burning fossil fuels in the first place, via windfarms, solar, tidal, nuclear or other means. Hydrogen isn't really a "fuel" so much as an energy storage medium.

There is currently large investment in just this. E.g. something from my company I can share as it's public - a 500 with potential for 100MW electrolizer site in Spain.

Cummins Press Release - Hydrogen Plant

trolling.

I've not disagreed with anything technical you've said, that was other people,.

I just think the argument that in most cases they shared castings with the far more popular petrol versions in the 90's makes more sense.

The performance argument doesn't hold up because they don't rev anywhere near a 70 year old petrol production engine design. And the cam profiles of turbo diesels aren't anywhere near as aggressive as NA petrol engines, there's neither the need nor the ability high compression means less valve overlap (need) and less clearance to the piston until further around TDC (ability).

And that the emissions argument falls down on things like I don't think it's possible to build a DOHC unit injector cylinder head in a car engine sized package? The injectors are just too bulky. So for the pre DOHC engines the complexity argument doesn't hold up as DOHC wasn't an option.

So Euro 4 wasn't possible without common rail, but DOHC wasn't possible without it , not the other way around . And SOHC persisted for at least another generation of emissions rules.

I'm sorry @thisisnotaspoon but you are incorrect and I'm not going to debate this any more with you as you've ignored most of my explanations that I've spent quite some time and effort on.

Hydrogen is well and truly in the future of cars

Nah I totally disagree. We've already got the BEV cars, now we just need them to be cheaper, we need more charging stations, and there needs to be on-street charging. The first two are happening pretty quickly, and the on-street charging is already being worked on. The massive advantage, apart from mechanical simplicity, is the fact that electricity supply is already everywhere and we have plenty of it.

The number of battery discoveries and innovations every month is pretty high, not least because half the modern economy benefits from it not just cars so many industries are investing in it. Right now, BEVs work, provided there is access to charging. Hydrogen vehicles really don't, and we'd need huge technological developments and infrastructure investment to do that. So why bother, when BEVs work and are only going to get better?

EDIT the above is all about passenger cars and vans btw.

And that the emissions argument falls down on things like I don’t think it’s possible to build a DOHC unit injector cylinder head in a car engine sized package?

Not sure what you mean - is this an example of an argument that's null, or you think that's currently the case?

My Passat is a DOHC engine with unit injectors, and it's Euro 4.

Hydrogen is well and truly in the future of cars

My personal view is that for passenger cars BEV's will be dominant, and pretty quickly.

We're already up to 200-300 mile range which is plenty for the vast majority of journeys, and technology is progressing rapidly. Infrastructure will need to develop, but with future smart grid type solutions becoming a reality that will help.

For uses where battery capacity will be more challenging, e.g. HGV's, excavators, trains etc I see Hydrogen as being dominant for some time. Likely initially using it in IC engines, transitioning to fuel cells in the future.

I wonder about powering an HGV on hydrogen. I am not sure you'd be able to get enough H2 in a sensible sized fuel tank to make much of a long journey.

H2 has about 2.6 times the energy per kg of diesel, but even in liquid form it's 11 times less dense, so that means a tank 4x as big as the current HGV tanks even if you were able to liquify it which itself takes a hell of a lot of energy. Diesel's already liquid.

And you'd not be able to liquify it in practical uses I don't think.

Toyota are doing a lot of development with H2 both ICE & fuel cell/electric & say they could have a truck ready for sale in two year.

https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/toyota-tapping-hydrogen-produced-with-geothermal-energy/

Agree. Aside from the production itself efficient liquidation, transport and storage are big deals.

A truck fuel tank isn’t that large, so a tank 4x larger would be a viable solution especially given it would likely be designed in. It would likely actually be more than 4x bigger as the tank will need to be both stronger and (I think?) insulated.

Once batteries are capable of displacing hydrogen in trucks they will I think. It’ll just be simple economics defining which is used as technologies develop.

markwsf

Free Member@mrmonkfinger – thanks, I hope these replied are interesting / useful and not coming across as a bit lecture / I know better ish.

I'm certainly enjoying them. Will have to move on to YouTube to see some of films of pushrods in action soon, though 🙂

H2 has about 2.6 times the energy per kg of diesel, but even in liquid form it’s 11 times less dense

It also burns at very high temperature, so that causes NOx pollution. To lower the combustion temperature, the engine has to run very lean, so you get much less power for the same capacity engine.

I think fuel cell vehicles are much more efficient than hydrogen ICEs. Fuel cells might have a future, I doubt that hydrogen ICEs do except as a niche thing.

Hmm, re HCVs one would assume it's possible to use the same tech as a BEV and just stick a h2 tank instead of a battery. It'd be packaged differently of course but we've already shown it's possible with things like the Hyundai Kona. You'd have the front end of the BEV version and the body and back end of the petrol version with a different fuel tank.

Because drivers’ earnings depend on fares, Goldstone said, “if they have to spend 40, 50 minutes, an hour, two hours plugging a car in in in the middle of the working day, that for them is just not acceptable.”

Good job it doesn't take that long then.

Nah I totally disagree. We’ve already got the BEV cars, now we just need them to be cheaper,

And what about sustainable? How can anything that relies on digging rare crap out of the ground and putting it through complex, energy hungry and polluting processing before it can be used? Sounds familiar by any chance??

Batteries are not sustainable and no amount of technology into re-processing will change that. It is not scalable for demand. Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe...75% of the universe is Hydrogen and we can create as much as we want easily and cleanly and the byproducts of its use are just water.

The future will be a mix of all kinds of technologies...including conventional ICE engines burning sustainable synthetic fuels.

H2 has about 2.6 times the energy per kg of diesel,

Damn sight better energy density than batteries. Nothing can beat diesel and petrol...whatever the solution compromises will have to be made. The specific application will determine which compromises will be made. Domestic cars BEV might very well dominate...commercial applications then synthetic fuel burning ICE hybrid or hydrogen fuel cell might win out, big lorries and other industrial vehicles then hydrogen is by far the most sensible solution. It'll be Horses for courses.

I wouldn't be at all surprised if diesel and petrol engines will ever be fully retired. There will be a few very niche uses where only petrol or diesel will do.

also burns at very high temperature, so that causes NOx pollution. To lower the combustion temperature, the engine has to run very lean, so you get much less power for the same capacity engine.

True.

Modern natural gas engines (methane, similar to hydrogen) run very lean indeed, and this is linked directly to NOx. Airflow becomes important, hence high pressure ratio turbocharging, high energy ignition systems and significantly worse transient performance compared to Diesel. The resultant engine out emissions are very good though, so whilst diesels need aftertreatment lean burn NG often does not. That'd be a challenge if it was a direct replacement in a vehicle so would need to part of a hydbrid type system (likely IC engine driving a generator then the vehicle is electric drive which is quite a common arrangement already)

would need to part of a hydbrid type system (likely IC engine driving a generator then the vehicle is electric drive which is quite a common arrangement already)

I'm pretty sure a fuel cell EV would be more efficient.

And what about sustainable? How can anything that relies on digging rare crap out of the ground and putting it through complex, energy hungry and polluting processing before it can be used? Sounds familiar by any chance??

It does sound familiar, and that's the point. I'm not saying BEVs are necessarily the best choice, I'm saying that's what we'll get. And in the future, because BEVs will be well established, they'll come up with new battery tech that won't be as problematic. If you are a FB user find phys.org and like the page - you'll get a few stories a week about developments that are solving these issues. Because now, there'll be a shit-ton of money behind it. Companies are paying techies to tinker in labs, this is really really cheap. For widespread H2 adoption we'll have to invest massively in infrastructure and simply hope that it'll take off. That's a harder sell to investors.

Batteries are not sustainable and no amount of technology into re-processing will change that.

Odd thing to say - there is clearly SOME amount of technological development that will change it - what's not clear is if that's possible or not. There are lots of ways to make batteries, I think sodium ion batteries are a front runner.

Damn sight better energy density than batteries.

But as we've said, BEVs work. If you view H2 and BEV as competing technologies, I can't see that H2 will win out for a long time, given the political and economic climate even if the storage problems can be overcome.

would need to part of a hydbrid type system (likely IC engine driving a generator then the vehicle is electric drive which is quite a common arrangement already)

I’m pretty sure a fuel cell EV would be more efficient.

I agree. If the IC engine approach is used I would only imagine this being an interim as fuel cells develop. I'm not up to speed on fuel cell capabilities or developments so don't know how likely this would be.

The later part of this thread reminds me it's time to start getting a bit more knowledgeable around the new techs to avoid getting stuck in the past !

I wonder how they'd stop water condensing everywhere on a cold start with an H2 ICE engine? I mean they have made it work so presumably they've decided it's not an issue. Maybe you'd need a bleed valve on the exhaust like you have on brass instruments!

But as we’ve said, BEVs work. If you view H2 and BEV as competing technologies, I can’t see that H2 will win out for a long time, given the political and economic climate even if the storage problems can be overcome.

Well BEV's don't really work do they? I guess it depends on what you define as work. They move, but they're nowhere near as convenient as a petrol or diesel engine interns of range and time to charge vs. filling up a tank of fuel.

But H2 engines also work by the same comparison...its established technology both in fuel cell form and ICE form. Yes there is a challenge with distribution but you can generate hydrogen anywhere by renewable electricity generation so less of an issue even compared to oil and petrol where it has to be moved all over the country. Hydrogen can be generated locally. Yo. might not get as much range out of a tank of H2 but if it only takes a minute to fill up compared to 30 mins or so for a BEV then its not a huge problem.

Odd thing to say – there is clearly SOME amount of technological development that will change it

Well improve it but not transform it. The best Elon Musk has come up with for spent car batteries is to repurpose them in his power walls which is just kicking the can down the road...what then once the battery performance degrades beyond being useful for that? You're into heavy, energy hungry, expensive and polluting reprocessing of precious earth elements.

But anyway, my point was that these technologies and solutions in the future world wont be competing. There wont be a one single solution for everything. There will be a number of different solutions for different applications. We're never ever going to see battery powered aircraft for example. Well airliners at least.

There will be a number of different solutions for different applications.

This.

It will be dynamic and change over time as technologies and markets develop.

There isn't and doesn't need to be a one-size fits all solution.

There might even be the odd pushrod diesel engine in the mix 😉

I wonder how they’d stop water condensing everywhere on a cold start with an H2 ICE engine?

It's not a problem as far as the engine operation goes. The same thing happens with petrol or natural gas engines. Hydrocarbon fuels are compounds of hydrogen and carbon. When that is oxidized, the hydrogen combines with oxygen to form water, the carbon combines with oxygen to form CO2. If you only do a short run in a petrol car, the exhaust system doesn't get hot and the water vapour in the exhaust condenses. Combined with CO2 and NOx, this forms carbonic acid and nitric acid, you basically get acid rain in the exhaust. If you only do very short runs in a car, the exhaust system will rot out because it never gets hot enough to evapourate the water.

The same thing happens with petrol or natural gas engines.

I'd have expected much more with a H engine.

Well not sure of the chemistry of it, but hydrogen engines can run a hell of a lot leaner than petrol or diesel engines. Like upto ten times leaner, one of the many benefits of H2 over petrol and diesel, so you don't need to add so much fuel to start when the engine is cold, so less fuel in the mix means less H2O production. Not sure wether H2 produces more or less H2O relative to petrol or diesel but can't see how it is a problem or a blocker. There are more tricky problems to sort out to productionise H2 engines rather than concerns around water condensing in the exhaust.

Of course using H2 as a fuel for aircraft means production of more contrails which have a global cooling effect due to reflecting solar energy back into space so a potential proactive way to combat climate change. Over the 24hrs following the global grounding of aircraft immediately after 9/11 there was a definite step increase in global temperatures measured as a result of an instant removal of contrails reflecting solar energy.

so less fuel in the mix means less H2O production.

It also means less power. To make the same power, you need to burn the same amount of fuel, provided that's done with the same thermal efficiency. Therefore you need a larger capacity engine to get the same performance out of a hydrogen ICE. You're burning the same amount of hydrogen, so you'll produce the same amount of water. The lean burn engine will produce much less NOx though because the combustion temperature is lower.

I’d have expected much more with a H engine.

A typical petrol molecule is C8H18 (octane). That will produce eight molecules of CO2 and 9 molecules of H2O. Hydrogen has an atomic mass of 1, carbon 12, and oxygen 16. If my arithmetic is correct, one mole of octane has a mass of 114 grams and will produce 372 grams of CO2 and 162 grams of water when burnt. As a ballpark figure, a litre of petrol will produce roughly a litre of water when burnt.

A kg of hydrogen will produce 18 kg of water. So yes, a hydrogen vehicle will produce more water, but petrol vehicles also produce a surprising amount of water and it's not a problem as long as the vehicle is run long enough to get the exhaust system hot.

hydrogen engines can run a hell of a lot leaner than petrol or diesel engines

How come? (serious question)

hydrogen engines can run a hell of a lot leaner than petrol or diesel engines

How come? (serious question)

That statement isn't really correct. Petrol engines generally run close to a stoichiometric fuel-air mixture, which means that there is exactly enough oxygen to burn every bit of fuel. For maximum power under acceleration, it might be slightly rich, this extra fuel helps to cool the charge. For maximum economy while cruising, it might be slightly lean. With carburetors and port fuel injection, this was necessary to get the charge to burn properly. If the mixture is too lean, you'll get combustion problems. Also, you need to keep the combustion temperature low enough to meet NOx emission standards. After emissions rules were introduced in the 1970s, compression ratios had to be reduced to lower the combustion temperatures, which caused huge drops in power output for performance cars. Direct injection engines can run leaner by injecting fuel so that there's a rich mixture around the spark plug and a leaner mixture elsewhere. Compression ratios on modern direct injection systems seem to be much higher too, obviously they have put a lot of work into understanding the combustion process and how to control combustion temperature. Any modern engine has an oxygen sensor in the exhaust and continually adjusts the fuel-air mixture according to the conditions.

Diesel engines use a completely different combustion process. They have a very high compression ratio and direct injection. The air charge is compressed so that it's hot enough that the fuel burns as soon as it's injected. They vary power by altering the amount of fuel injected, so the fuel-air ratio is much more variable than the fairly stable mixture in petrol engines. If you look at tractor pull competitions, they crank out incredible power from turbo/supercharged diesels by just turning up the boost and injecting massive amounts of fuel. Those things send a plume of black smoke up, the combustion efficiency doesn't matter, it's just a matter of pushing in as much air and fuel as the engine can withstand.

Hydrogen burns at quite a high temperature if there's a stoichiometric fuel-air ratio, so it causes NOx pollution. This can be reduced by using a leaner mixture, but you can't burn as much fuel with a very lean mixture so the power output is reduced. Basically, once you go leaner than a stochiometric ratio, the engine power starts dropping for the same volume of air. If you have to run lean under full throttle to meet emission standards, you have to build a larger capacity engine to produce the same maximum power output. That larger engine will be heavier and more expensive to produce. Running lean to meet emission standards is a drawback, not an advantage.

Nice description of the combustion processes above 🙂

Re Gas engines - (either Natural Gas or Hydrogen - same broadly applies) can run at stoichiometric or very lean. At stoichiometric there are emissions issues so you'd need aftertreatment. Lean can avoid this need, but at the expense of increased cost of turbocharging (to avoid dropping power you increase the density of the air, so get more mass of air into the engine), a more expensive ignition system and "transients" (ability to cope with rapid changes in power or speed) become worse as you're reliant on the turbocharger speed to drive enough air in to the engine to allow enough fuel without misfiring etc.

You can't just add more fuel to cope with transients like a Diesel can (within limits - usually imposed by black smoke creation) as a gas engine will "knock" which is a very bad thing.

I expect that due to the above a passenger engine will run "as lean as possible" which actually won't be that lean, so will still need aftertreatment.

Note Diesel and Petrol can both run vey lean as well, and as time has progressed run leaner and leaner as technology has progressed to remove the limitations to doing so. As will all these things it's a compromise between many factors. Emissions, power density, driveability, misfire etc.

Petrol engines can run upto 34:1 AF ratio, but hydrogen could go upto 180:1 AF ratio. Whether or not it makes sense to run them at those lean rates in the real world is another matter, but similarly though petrol CAN run at upto 34:1 AF ratio doesn't mean there are any production engines out there that do. The benefits of the higher AF ratio is that NOx can be addressed/reduced and they are easier to start...however downside is reduced power...but you don't meed max power all the time so no reason why you couldn't run super lean when cruising at low power levels bagging better economy and emissions, then as you demand more power the AF is changed to delver the greater power. Or even marrying an H2 ICE to electric in a hybrid so the engine needs to only ever run in a mode where it is minimising NOX and the electric motor boosts power.

Appreciate that H2 engines might be larger and heavier to achieve similar power levels to petrol/diesel...but so what....the weight of electric motors and batteries in BEV's is hardly the light weight solution. We're never going to beat petrol and diesel engines so lets accept that (well not in the next hundred years at least). Petrol/diesel is just too good and convenient a fuel. So again...H2 engines don't have to compete with petrol/diesel engines and power plants....they need to compete with BEV's and whatever other alternative power plants there are out there. Provided there was a decent Hydrogen network out there then moving to hydrogen fuel cell or hydrogen ICE would be a much more familiar and convenient step to emissions free motoring for most people used to fossil fuelled cars. Future generations might develop different behaviours and drive different solutions - maybe even car free solutions...but thats decades in the future.

As an end result of all the above I'd expect a production hydrogen engine to be broadly comparable to a comparable petrol engine in terms of power density, in terms of power density and need for aftertreatment.

* Disclaimer - this topic is outside of my professional experience and so is now into just "my opinions".

There are some interesting papers on this from a quick google search.

One interesting conclusion - port injection hydrogen about 83% of the power density of gasoline, using more advanced techs potentially around 115%. So broadly comparable.

MDPI Applied Sciences paper

Another paper

Another thing to consider is the direction that F1 engines have gone in. They drastically reduced the maximum fuel and fuel flow to encourage economy. The engines are turbocharged, with the turbo also able to drive an electric generator (so basically a petrol-electric turbo-compound). To some degree, the ICE functions as a gas generator for the turbo-electric generator. It's hard to know how much of the public statements are just bullshitting to throw rivals off, but the Merc people said that they incorporated ideas from diesel combustion to improve combustion efficiency. Those engines are getting better than 50% thermal efficiency, which is impressive.

Thing is, using the ICE as a gas generator means that you need to find the optimum level of energy going out the exhaust (i.e. is it better to extract the energy through the ICE or the turbo-generator?) Just bolting a turbo-generator unit onto an existing engine would not be optimal, you'd need to rethink the entire engine and combustion process.

Those engines are fantastically expensive, but the basic concept might be applicable to things like HGVs which burn a lot of fuel and do massive annual mileages. Fueling them with a biodiesel/hydrogen mix might give better energy density than BEV tech and help with the NOx emission problem. Having them idle for 30 minutes while they stop to recharge batteries would be expensive down-time, so chemical fuels would avoid that. Not saying that's what'll happen, just that that's probably the types of things that engineers will be looking at.

Hydrogen burns at quite a high temperature if there’s a stoichiometric fuel-air ratio, so it causes NOx pollution.

At stoichiometric there are emissions issues so you’d need aftertreatment. Lean can avoid this need

Hang on. NOx emissions happen because there is 'spare' oxygen in the cylinder that hasn't got fuel to react with so it reacts with nitrogen at high enough temps. So that seems to me that running lean would create more NOx and running a stoichiometric mixture wouldn't have this problem. That's why diesels create much more NOx, because there's always hot air in there at some point and at light loads there's a lot. That's what EGR is for. Where am I wrong?

To some degree, the ICE functions as a gas generator for the turbo-electric generator.

This is what Toyota did with their first hybrid car. It's both a series and a parallel hybrid in varying amounts depending on load and road speed. Very clever bit of kit. I don't know if trucks use Toyota's hybrid system or if they could, however.

So that seems to me that running lean would create more NOx and running a stoichiometric mixture wouldn’t have this problem.

The combustion isn't instantaneous (i.e. detonation, which destroys engines). In a petrol engine, the spark plug ignites the mixture in one place. The flame front spreads out and burns through the charge. Controlling the timing and geometry of this is a big part of combustion chamber design. Remember that the mixture is ignited before the piston reaches top dead center, so the combustion chamber is still getting smaller, then it expands as the piston starts on the power stroke. If the ignition timing is too advanced, you'll get detonation. If it's too retarded, you'll lose power. At high revs, it needs to be advanced, at low revs, it needs less advance. Because the combustion isn't instantaneous, you have nitrogen and oxygen mixed at high temperatures and pressures. If the combustion is too hot, some oxygen will combine with nitrogen instead of fuel and produce NOx.