Currently Head of Bikes at The Rider Firm, Mike Sanderson has over 20 years of experience in the bike industry, where his career has seen him have a hand in some much-loved and admired bikes and brands. Hannah found out how he got here, and where he thinks we’re heading next.

Words as told to Hannah, photography as credited

Hey, this feature looks even better when viewed viaPocketmags; you get the full graphic designed layout on your device FOR FREE! It’s not quite as beautiful as the paper magazine but it’s better than a basic webpage.

Mike got into bikes as he started secondary school, back in the early days of mountain biking. His dad was an RAF engineer so he’d been brought up with an eye on fixing things, and there was plenty of room for improvement on those early bikes. A college engineering course led to a surprise (to his parents at least) entry into university to study Computer and Product Design.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

MS: That was, I think, when I decided I wanted to be involved in bikes. Through the engineering qualifications I did at college, any time we got free rein in terms of our projects, it was all around bikes, because that’s what I knew. I was still riding a lot… still breaking things. This was back in the late 90s, early 2000s. So, bikes were still really kind of shonky in a way [and] still lots of weird and wonderfuls happening… still lots of breaking happening. As a fairly hard rider, and also having that engineering thing, I was like, ‘Well, why have they done it like that?’ or, ‘If they’d done it like this, it could have been better’.

This makes Mike one of those rare breed of people who end up doing what they set out to do. Although he says he doesn’t really use his degree much, it gave him a foundation – and some designs he could put in his CV.

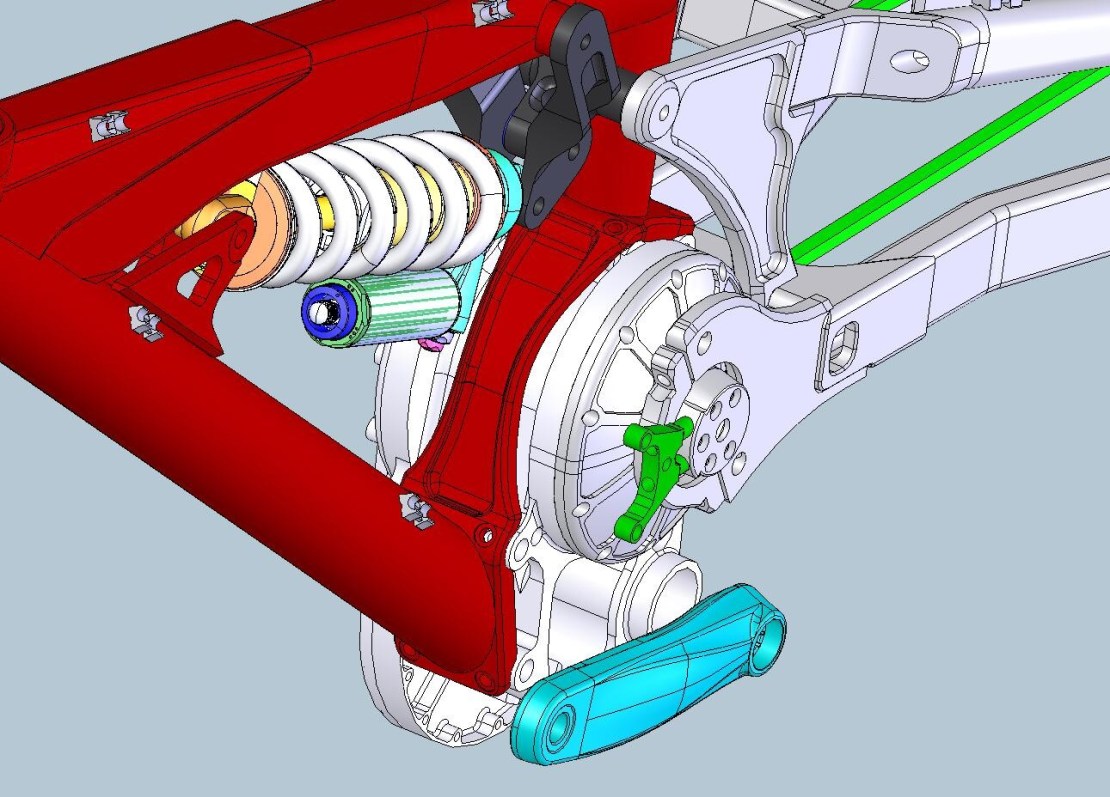

MS: The final year I designed a six-bar link bike, suspension frame kind of thing. And then also a linkage you could adjust the travel by kind of having a screw on… It was very, very big. And on a modern stage, it would not be deemed usable! But I suppose it gave me enough that [my] CV got attention in the industry.

But I didn’t fall straight in. After uni I was a project manager for a pharmaceutical company. I did stuff for veterinary, tattoo and piercing (weirdly), which was sort of yin and yang… veterinary prescription drugs and then tattoo and piercing conventions run by Hells Angels. So, a lot of project management, a lot of laws and things you had to do. I was 22, 23 years old. You’re not an adult then. [The work] made me realise that – there are some laws behind this and people will get in trouble, including yourself, if you don’t do it right.

That attention to detail and ability to manage a big project accords with the reputation I’ve come to know Mike for. In a world with many enthusiasts, it’s a set of hard skills you don’t always find. He’s now back at The Rider Firm for a second time – surely a good sign when an employer wants you back. I asked him to run us through the different bike companies he’s been at.

MS: While at college I worked for Alex Moulton Bicycles. Really bespoke, handmade bikes in Bradford on Avon, in Wiltshire… That gave me a really good sort of micro-climate of a production line because they did pretty much everything in-house. Theirs was unique, but still gave me an insight. I quit to go to university.

After the medical side of things, I was a junior product manager at Raleigh… pretty cool. One of the youngest in the team, and still racing downhill – not well, but still giving it a go – and racing BMX.

After a year or so, they gave me the Diamondback brand to look after, mainly the BMXs. At that point, Raleigh was Raleigh UK, Raleigh Germany, Raleigh South Africa, Raleigh USA… they were all kind of disjointed. It was very weird, but we were buying BMXs from the American team based in Seattle. So everything was built like a tank, meant for dropping massive stair sets because that was their scene. Whereas the UK, being closer to Europe, was starting to become lighter weight, smaller, higher rise bars and stuff like that.

So I redesigned and redeveloped a whole range of BMXs for Diamondback. We doubled our sales in the first year and doubled them again in the second. I think that was the point when the big bosses at Raleigh went, ‘Hang on a minute, this young lad seems to know what he’s doing!’

I got a bit more given to me. I was working with people like Martyn Ashton, we did the Ashton Diamondback team with Sam Pilgrim, Blake Sampson, Katy Curd, Ben Savage, Kurt Brain… It was really cool. They were young and up and coming then, but they’ve all made their own successes. It was great to work with Martyn as well. We learned a lot from him and we did some pretty unique bikes.

One of those bikes was the Diamondback Sabbath gearbox bike, way back in 2007. Mike was certainly ahead of his time with that one.

MS: It’s quite cool watching everyone now [making gearbox bikes]. I remember being in Cwmcarn car park with the guys from Gates Drive and Karlheinz Nikolai, whose G-Boxx Gearbox unit we were using at the time. Now you’re seeing all the buzz with Gates and all the guys [with the World Series prize purse]. It was pretty cool. It took a lot longer, if I’m honest, to get to this point than I thought it would.

In 2007, 2008, I thought that bike was going to take off more than it did, but it had its reasons. I thought in the next five years gearbox bikes were going to be the norm, especially for downhill. It took a lot longer, but it’s cool to see now.

After Raleigh, Mike joined Go Outdoors to eventually be the brains behind the Calibre Bossnut, arguably one of the most influential bikes we’ve seen hit the market.

MS: I joined with an idea to create their own bike brand. But I was also the buyer… so I was ‘ juggling’ two very different things, but it was unique in the sense that I could see gaps in the range. Go Outdoors was then stuck with a similar stigma as Halfords – big brands didn’t want to come and play with us. So it was a chance to plug those gaps in our range with a brand that subsequently became Calibre.

I started with two hardtails. By the time I left, I think the range was about 30-something bikes. And then I also started another brand called Compass, which was kind of utility or family bikes, and then Wild Bikes, which was a kid’s bike brand. So that job snowballed dramatically!

This was a mixture of designing from scratch, open moulds, and working with factories and their existing capabilities – all intended to keep costs down while developing the range of bikes needed. At that time, the Bossnut was born. When I suggest it was pretty revolutionary, Mike thinks it seemed like an obvious choice.

MS: I’d like to think I’m pretty good at putting the rider’s hat on or reliving my riding journey… For me, it was really fairly obvious: everyone wanted a full-sus bike because it makes riding easier, more fun. You can progress better. But of the bikes that were around the price point of the Cycle to Work scheme then, there was only maybe one [full sus bike], I think Boardman had one under the Halfords banner.

So it was fairly obvious: if we could build something that had good geometry, good well-thought-out parts, tyres that would actually grip at trail centres – where most people were going to take their bikes – good brakes that were going to slow them down with confidence… It wasn’t revolutionary in my mind, but it seemed to arrive and everyone went ‘I can’t believe no one’s done this before!’.

He went on from there to Privateer, which was another revolutionary bike at the time – similarly budget-minded but in a slightly different way.

MS: I like to think the Privateer brand is kind of the next step up [from a Bossnut]. I spoke to a gentleman a couple of weeks ago who was on a new Bossnut – I was explaining to him that I had a hand in the brand (because he had a problem and I was fixing it, he goes ‘Oh, you seem to know what you’re doing!’). And I was explaining that… [the Privateer might be right for him] maybe in two years when he’s built his skill level.

That’s kind of what drew me to the brand back then. For the rider who’s built their skill base and knowledge, riding much faster, much harder, much more difficult terrain, but still conscious of the money they’ve got to spend. They can look at something really unique, really built for them – but isn’t the mega boutique money that you can definitely spend on bikes at the moment. That’s what drew me to [Privateer]. In terms of the development of the Gen 1 bike, that had already been done; I landed after that but did have initial guiding into the Gen 2 bikes. Then I got headhunted to join the Whyte team, and that was great. Right after Covid kind of finishing, so lots of difficulties in getting stock, and then lots of difficulties with stock arriving you didn’t necessarily want! I was also part of the rebrand of Whyte, which was not easy, but definitely needed.

Obviously, all of the newer bikes that have just been launched, I had a hand in with the team there. Things like the ELyte bikes, the new EVO version, which was really cool. I was a big kind of push behind that, being labelled as a ‘rad dad’, where you’ve got an hour and a half to spend riding your bike. That EVO bike is really designed for that hour and a half to get out and maximise your riding. And then there’s some new bikes I don’t think the Whyte team have launched yet, so keep an eye out! It was great to work with the team; there are some really clever guys and girls in the Whyte team.

I was a small cog in a big machine, but I felt as I left Whyte I’d done a lot there to help the brand move on… So it was quite nice to be part of their next step.

After Whyte, it was back to The Rider Firm (home of Privateer) as Head of Bikes. Mike said it was a chance to progress his career, but it also feels like another chance to steer the next generation of bikes and the next steps for Privateer and Cairn, the e-gravel range. Both are quite different brands, but both have a rider-focused and value-driven element to them. Like his previous work, they’re not necessarily boutique, chi-chi, carbon bikes. I wonder if that is a deliberate choice?

MS: It bugs me when I see people who’ve spent a ton of money! I think we as an industry could definitely do better at this. We allow people to go and spend – or tell them to go and spend – a thousand pounds on a new set of suspension forks, or more. And then you’re looking at their current set of suspension forks and go, ‘Well, the reason why you’re not getting the most out of them is because they’re not set up properly!’. We’re not very good at educating people. We throw too much jargon and tech at people and don’t make it easy for them to get the most out of what they’ve already got.

I probably should keep my nose out a bit more often, but I see people with their fork the wrong way around or things like that. I’m fairly good on the spanners, so I always try to help people. We’re very fortunate to live where we are [Forest of Dean]… you’ve got mums, dads, kids, all in a sort of melting pot. It’s always good to kind of sit back, especially waiting for [his sons] to come back from coaching sessions, and just look at what people are riding, listen to conversations, see how bikes are set up, that kind of thing. It helps me see what’s going on in the real world.

I think building with a rider focus is the only way. You can design bikes by AI, spreadsheets, or just by ‘Oh, I’d like to be like Santa Cruz’. Well, you could do that quite easily, but is that moving you any further forward? Is that actually the right thing for the rider? Sometimes maybe not. It’s about paying attention to what really makes a difference.

I think as well in the current climate, obviously we saw the price hikes during Covid. I don’t think any of those retail prices were ever realised by the brands. I might be wrong… But now you see the sales… And that’s a real indicator of what the rider is willing to pay.

The conflict between ‘sell more stuff’ and ‘don’t waste your money’ seems to be something that Mike accepts is part of being in the bike industry.

MS: There’s no bad bikes in the marketplace now, really. You’d have to work really hard to find something that’s categorically bad. There are some fantastic bikes and making sure people get the most out of them is one thing [we could improve].

As much as I love it, and it’s full of amazing people and everyone’s heart is in the right place, we have to understand that it’s a fashion industry, and it’s a consumer industry, where we need people to [buy things] to continue the industry and to grow. So there is that kind of push on ‘this thing has got X or Y’. That’s got to be understood. There are some big benefits to some of the stuff, but I think first and foremost, if we can get people on the products they’re already using and get the most out of them, that would be really good.

Making sure there are no bad bikes in the market is the job of people like Mike. It’s them who decide what to design next and then go through the process of specifying, prototyping and testing. This is a process that he thinks is particularly challenging because of the pace of change in ebike motors. He explains the timeline.

MS: It roughly takes about two years, maybe a bit more depending on what’s going on, to develop an ebike… Obviously, you’ve got to decide as a business, ‘OK, we’re going to build a 160/170, ebike, full power’. So then you’ve decided what you’re going to do. Now, who are we going to get in bed with in terms of a motor and battery system? You’ve got to go through the pros and cons of everyone, and there are more pros and cons than you think. It’s not just like, ‘Oh, Bosch are the best’. For instance, Bosch has a minimum order quantity, and we wouldn’t be easily able to hit that. So that potentially rules them out. There are ways and means around that, but then it adds complexity and cost.

You’ve decided you’re going to build a bike, you’ve decided what you’re going to use as a motor and battery system. You’ve then got to decide all the other bits and pieces. You’ve got to build a frame – whether that’s aluminium or carbon. Either way, you’ve got to design it. You’ve then got to open all the moulds. You’ve then got to test it. And testing for ebikes is a lot more complex than it is for a normal bike. Ebikes fall under the ‘Machine Directive’, so there’s a lot more testing for that. You have to go and EMC test it, which is like putting it in a massive cube that looks like something out of James Bond, and bombard it with radio waves to make sure it doesn’t do anything weird as you ride past a TV station or a telegraph pole and doesn’t set pacemakers off or change the TV as you ride past someone’s house or something. It’s pretty complex! So you’ve got that.

You’ve got mechanical testing as well, which is much more strenuous on an electric bike. All of this is fine if everything passes, but it can be really complex, especially with aluminium, if it fails.

EMC testing, I have an example – I won’t say which brand it was – where it was doing something it shouldn’t. And you can’t see it, it’s radio waves! You’re trying to work it out, you’re wrapping bits of tinfoil around certain wires to insulate them and try to see what thing is [causing it]. And it took us like four days of repeated testing – that’s money being spent. It’s quite difficult, even though the electric components from the brand have to be EMC tested, but they just lay it out on the table and turn it on. But as soon as you put it inside an aluminium frame, which can resonate the signals, or wrap them up [things can happen]. What it ended up being was the wire for the controller – which we thought we’d done a good job by wrapping it around the handlebar to make it nice and neat. But effectively, we’d made a magnet! [We fixed it] just by unwrapping it. But we thought we were doing a good job trying to make all the cables nice and neat; we didn’t think that it would be a problem – but yes, it was.

So it adds time. All the time you’re doing this, lo and behold, component manufacturers are obviously trying to push their brand as well because they’re looking [at everyone else] thinking we need to be better than those guys. So their engineers are pushing forward and faster.

All the while, you’re still going through your testing ready to launch. And then six months later, hypothetically, there’s a new [motor] and you’re like, ‘I’ve only just launched this!’

Next time you mutter to yourself about bicycle standards, perhaps this tale will temper your frustrations a little. But seeing people out on the trail and having fun is what makes it all worth it for Mike, and has kept him motivated for the last 20 years. He’s pretty proud of still being here. I wonder where he’d like to see it go next?

MS: It would be good for the industry to maybe talk a little bit more. I understand we’re all technically in competition, but there are definitely some things I think we could all be better at. There are certain things we’re all going to face as industry challenges. Obviously, we’ve got Mr Trump causing some potential issues for the Canadians and the many brands under that banner. Who knows what he’s going to do with Taiwan and China where a lot of things are made? [Ed’s note: this interview took place before the USA announced worldwide tariffs. Mike’s crystal ball was right!] There’s going be some challenges over the next four years or so we’re going to need to look out for each other a little bit more… There’s definitely, I’d say, things we’re all going to suffer or need to work together to overcome.

I think [some] individual brands, the giants, no pun intended… they could stand up and potentially be heard. But if we all stood up together… we’ve got much more chance of being heard than individually.

It would just be phenomenal. I don’t have an answer, but it seems we’re still fairly fragmented and not standing shoulder-to-shoulder like we do at so many [bike] events.

Looking into the future and hoping it’s a bright one takes on all the more importance when you’re a parent. Through his sons, who both ride, Mike sees the potential for a great future for mountain biking.

MS: My 8-year-old has grown up with bikes. I’m just remembering my first mountain bike, it’s 12-year-old me versus this 8-year-old on a full suspension that’s got tubeless tyres with decent compounds, brakes that work. He’s got all the very best bits of what mountain biking is and what he does on a bike now… don’t get me wrong, there are kids out there even better than him.

I would say Little Fodders [the coached club Mike’s boys attend] is probably a good 50-50 mix between boys and girls. It’s just fantastic to see. I think that every sport says the future is kids, but I do think for us it’s that. Because I think they’re going to push what they’re seeing on YouTube, right? My 8-year-old watches YouTube and then he’s throwing whips on Sunday. Made me spit tacks because I can’t whip for love or money! And he was doing it; granted not the biggest whips in the world, but he was doing it with the right technique. He understood what he was trying to achieve and understood how to get it back in. I’m thinking, ‘Christ, by the time he’s ten, he’s going to be upside down and inside out!’ And I was having to work hard riding in front of my 12-year-old to keep him behind me.

I think that that’s something as a sport and as an industry we should be very proud of, just bringing that younger generation through. There’s definitely brands that have led that. It’s sad that brands like Islabikes are gone, but they should definitely get some massive credit for bringing some of those riders in. I think the legacy lives on in terms of getting kids out there. I do think that that’s something really to look forward to and a real positive, that there’s more and more kids, boys and girls, just getting into it and seemingly loving it. It’s great to see. It reminds me of what I was doing. My 12-year-old lad going off in the woods with his mates, building sketchy jumps, egging each other on to hit a corner with no brakes. The stupidity and fun I was doing is still the same – now it’s with much better kit!

It would be fair to give some of the credit for that ‘much better kit’ to Mike and the influence he’s had on bikes in the UK. Maybe you’ve ridden a bike he’s been directly involved in, or maybe you’ve ridden one that’s the result of another brand being given a kick up the bum to catch up. Here’s hoping for another 20 years of stupidity and fun in the woods.

New arrivals

-

Singletrack Bobble

£24.00 -

OG Ride and Shine Shirt

£25.00 -

Issue 163

£10.00 -

Beate Kubitz Classic Ride Print #127 Walna Scar Road

£44.99