History is harder to follow when it’s flammable

Like most people, I was dismayed to see the damage from the recent wildfires that levelled parts of Los Angeles. It was especially poignant as I suspected that I might know people whose houses (and lives) might have been in danger. It turns out that one of those people was Zapata Espinoza who edited Mountain Bike Action Magazine, and later Mountain Bike Magazine, for many years spanning the ‘Golden Age’ of mountain biking in the late 1980s, 1990s and into the turn of the century.

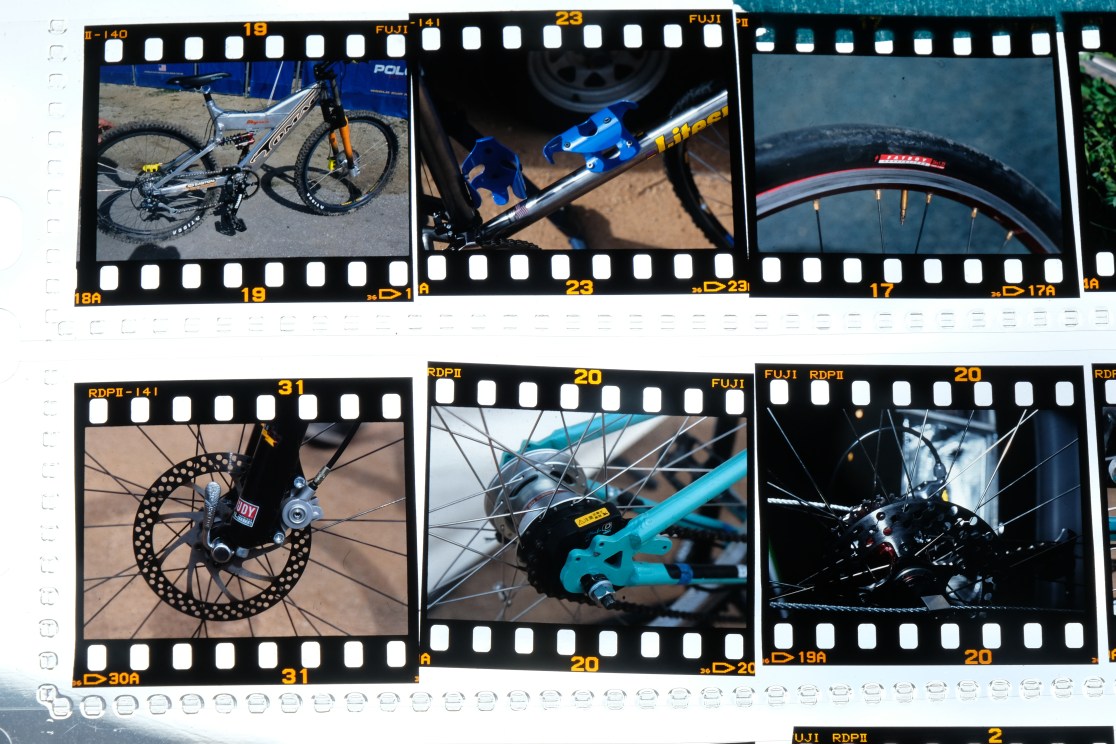

‘Zap’ was as embedded in the scene as you could have been back then. He reported on early races in the USA, then charted mountain biking’s spread into Europe and the racing battles that took place when the technical bike handlers of the US met the all-out speed of the Europeans. All the while, he shot photos (on print and slide film, back then) and documented the technical innovations that were emerging, like index shifting and rudimentary suspension, interviewing the likes of Gary Fisher, Paul Turner and Keith Bontrager.

Far from being an impartial observer, he was a fan as well, with his photos showing friendships with many of those early names: Ned, Tomac, Joe Murray. He had an impressive collection of early memorabilia too, including Olympian Paola Pezzo’s infamous gold lamé skinsuit, classic mountain bike frames and signed photos from the likes of John Tomac saying “Zap, you molded me like a ball of clay – Johnny T”.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

And now, all of that is gone. His house went up in flames, taking with it decades of magazine back issues, every mountain bike he owned and, devastatingly, his entire archive of photos from those early days of mountain biking: “…binders and binders of slides.” Gone.

Modern mountain biking is still relatively young as a sport: it only got its first World Championships in 1990 and Olympic recognition in 1996. Those innocent early days also saw the introduction of the digital revolution in magazine production and, later on, the slow move from film cameras to digital. However, much of the reporting of those ‘classic’ years was shot on film cameras, with the negatives posted to the editorial office with stories written on electric typewriters or early black and white Macintosh computers. The final magazine layouts were then set onto film separates and posted to the printers. There was no speedy way of transferring photos and files – hell, even our early issues of Singletrack had to be burned onto a DVD(!) and posted (or in several cases, driven through the night) to get to the printers on time.

By its nature, such a globally small sport had very few record-keepers. After all, for most of us, it was just a fun hobby we did at the weekend, so why should we document everything? Many of those early days simply weren’t documented, except for the odd Instamatic snap down the woods, or a story in a photocopied Bad News zine. In many cases, those early mountain bike magazine stories were the only report about a particular event that there was – and ever will be. This is why I’m so gutted for Zap, as those moments simply won’t happen again and every shot of transparency film was probably the one bit of evidence there’ll ever be of a particular scene.

And for every person who suggests that there’s bound to be a backup, I’ll point to an equal number of photographers who’ve never found the time, or the reason, to spend weeks at a scanner, digitalising every shot they’ve ever taken (and transferring those digital records to two, secure, off-site facilities…) purely for the sake of posterity.

It’s difficult to imagine, in this age where everyone shoots everything on their phones, that the necessary skills and expense of analogue photography in the ’80s and ’90s limited the number of people who could, or would, shoot photos and make notes and our history remains with them.

And so, I imagine, the (remaining) precious history of the early days of our sport, for the most part, is sitting in cardboard boxes under the stairs, or stacked in old magazines on shelves, or in the pile to be recycled next.

History may be written by the victors, but only if they still have the negatives.