After a lifetime of thinking it could never happen for him, Neil and friends set out to bag a Munro – on a handcycle.

Word by Neil Russell, photography by Pete Scullion

One foot in front of the other I keep telling myself. I’m losing them. I’m only halfway up and the sun is burning, the sweat dripping off me. Why are they going so fast? Why can’t I keep up? I know why I can’t keep up. I’m never going to be able to keep up.

“We can stop here. I’ll tell the others just to go on and we can either rest for a bit and keep going or we can take our time and go back down to the minibus and meet them there. This is a huge achievement already; it doesn’t always have to be about getting to the top,” said my Dad.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

It doesn’t feel like a huge achievement. It feels like another confirmation of the things I can’t do and would never be able to do. Another example of how I am different to everyone else. It’s the summer of 1999 and I’m in the Air Cadets. My Dad is doing his best to keep my spirits up and help me see things through a more positive lens. All I know is we’re halfway (if that) up Ben Lomond, not at the top of Ben Lomond and I’m a teenager who has lived his whole life with a physical disability.

Born with spina bifida I have problems with my right leg, meaning I have trouble with walking. I constantly get sores and have very little muscle tone or sensation in that leg. All I’ve ever wanted is to be like my peers. Keep up with them, do the same things as them, go the same places they go. I’ve always hated spending time with other kids and teenagers with a disability. It just makes me feel more disabled.

We go back down. We get in Dad’s car. We go home. Hills, mountains, getting out to the more remote adventurous places… it’s not for me.

Well, that was a bleak start to this story. It gets better. I promise.

Swimming is miserable, but bikes…

Getting up hills and out into those beautiful remote places that you see on social media and TV really didn’t feel like places that were ever meant for me. That all started to change when I was in my early thirties (nearly ten years ago now). In 2015 a friend talked me into having a go at my first-ever para-triathlon. It was to be my only para-triathlon. I naively thought it wouldn’t be too tough. I’d been a swimming teacher for about four years by then and as soon as I got in the pool at that triathlon, I realised the saying “Those who can’t do, teach” is abundantly true.

I struggled my way through the swim but then got to the bit I was really looking forward to, the handcycling part. Until about two weeks before this taster event, I had never even heard of a handcycle, let alone seen or tried one. On the day of the event, I met David Hill, an instructor from Castle Semple Outdoor Centre at Lochwinnoch who had brought along some handcycles for people to use during the event.

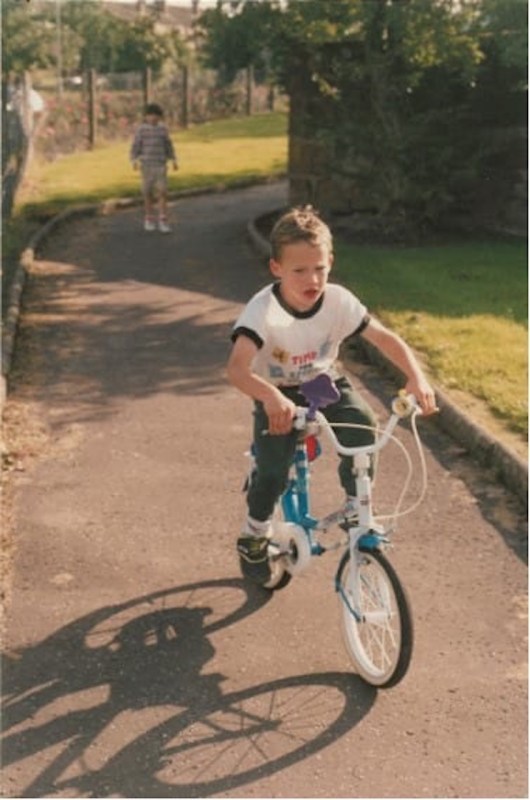

With the swim finally over I got onto the handcycle and set off. This rather clunky, manual machine ignited something in me that I hadn’t felt since I was about ten years old. Since struggling part-way up Ben Lomond at the age of 15, my health had changed dramatically, from having a below-knee amputation at the age of 18 to having a few years of constant struggles with problematic prosthetic limb fittings, infections and frequent hospital admissions. In the first few moments of sitting on that handcycle and turning the cranks with my arms, I remembered the power of the bike. Cycling had always been my go-to option as a kid as it meant I could keep up with friends, have a level playing field and go off exploring around my house and into the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. Here I was, about 20 years later, realising that the machine I was on could maybe, just maybe, give me back some of that freedom I had felt as a child growing up with a disability.

Out on the town

My love of handcycling just grew and grew after that day. With regular visits to Lochwinnoch to use the handcycle David had supplied me with, I was able to build up my experience and get my fitness up. Soon I was lucky enough to get a great deal on a second-hand handcycle from a friend, and that meant I no longer had to drive from Edinburgh to Glasgow to get out riding. It also turned out that there were a few other handcyclists in and around Edinburgh I was able to start riding with.

For the next few years, this is exactly what I did. Lots of road riding and cycle paths, which was great fun and really helped me build up my fitness and stamina, but I still felt that I wanted more from handcycling. As much as I enjoyed the joys of lying nearly flat and parallel to the road while contending with city buses, lorries and lost tourists in hire cars, I felt I spent so much of my time having to be extra vigilant about the relationship between me and the surrounding traffic that I rarely had the opportunity to take in what was around me. I wanted the views, the nature, the mountains.

A move back home to Stirling to be closer to family meant that Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park was once again within reach. However, the handcycle I was riding then was in no way up to the task of getting me off the roads and cycle paths and out onto the forest paths I desperately wanted to get back to.

At this point, I should really point out, that when it comes to ‘techy’ stuff, or even just basic mechanical understanding of cycles, this has never, and will never be my area of expertise. I like what bikes can do but fall asleep when people start telling me how they do it. Gear ratios, tyre sizes, cadence… zzzzzzz. So, this being said, I saw no reason why putting on a set of mountain bike wheels and tyres on my 100% road handcycle wouldn’t be the obvious solution.

More than just knobs on

As it turns out, there’s a lot more to adaptive mountain biking (aMTB) than just knobbly tyres. After some interesting forays onto rougher surfaces, such as Devilla Forest, and even a few attempts at solo bikepacking around Loch Rannoch and Loch Chon, I realised that the handcycle I was using wasn’t going to cut it, and nothing I could do to it would make it into something it really wasn’t designed to do.

Off-road handcycles really do need e-assist to help with the terrain and the hills yet they start at around £6,000 new and they aren’t the kind of thing you can just pick up at your local bike shop. I knew it was a big financial commitment but also knew it was exactly what I wanted to do. I once again struck it lucky with finding a second-hand off-road handcycle for sale in the Lake District and a post-lockdown trip meant I returned to Scotland with the machinery fit to get me out exploring. And boy, did that handcycle //photo// get me out there.

A whole volume could be written about where that handcycle took me, from bikepacking trips with my friend Rosie up to the Corrour railway station in the highlands to meeting the team behind Bike Trossachs and the famous Gravelfoyle routes. Eventually, I went riding with the ‘Ride, Drink, Pie’ crew down in Yorkshire and had to get carted off the moor by a local farmer in their Land Rover with the remnants of my handcycle in the back. To be fair to the manufacturer, Lasher Sport, I kicked the crap out of this handcycle for a few years, and my good friend David Bower, who I bought the handcycle from, had also kicked the crap out of it for over ten years, so it served us both well and truly went out with a bang!

Revisiting old dreams

Handcycling, getting into the outdoors, background in coaching and education… these were all parts of me that really came together in my mid-thirties. I wanted more people to get the chance to have the kind of adventures I was having and wanted to do everything I could to help make this possible. In the summer of 2022, I set up the Adaptive Riders Collective (ARC), a non-profit organisation based out of Callander in Stirling, where we run activities and get people out to experience the freedom and enjoyment that an aMTB has to offer. As my professional career rapidly went down the path of setting up ARC, my personal goals and achievements in cycling continued. At the Scottish Mountain Biking Conference in Aberdeen in 2022, Pete Scullion, Calum Hendry (Able2Adventure, Aviemore) and I started to discuss the possibility of getting me and a handcycle up a Munro – one of Scotland’s 3,000ft+ peaks – something I’d been wanting to do ever since that failed attempt in my teenage years. I remember vividly how, at that moment, a new part of the world seemed like it might just open up for me. As I sat there with Calum and Pete throwing about Gaelic names of hills that I’d never heard of and debating the likely challenges that each would throw up for us, my mind went into overdrive at the possibilities of getting me and a handcycle up my first-ever Munro.

With ARC taking off so quickly, it wasn’t until early 2024 that we got around to making plans and putting dates in diaries to start making that which we’d talked about for so long a reality. By this point, I was riding a Bowhead RX, which meant it was much more likely I might get to the top of this Munro without having to be dragged/pushed up too much by others. The Lasher I had been riding before was front-wheel drive and great for trails and gravel, but as soon as you start to tackle anything steep and loose, you’re wheel spinning the whole way as there’s very little weight over the front wheel. The Bowhead RX, however, is rear-wheel drive, so with more weight over the back, you have much better traction on the steep stuff. Having taken delivery of the Bowhead early in 2024, I really pushed it to see how steep it could go and a trip up and around Glen Finglas helped me to find out that, yes, the Munro plan was definitely within my grasp. After discussions with various friends who had walked/ridden up Munros, Glas Maol in Perthshire became the chosen summit to tackle.

Two wheels good, three wheels wider

I recruited friends Robyn Wilkinson and Keith Potter to take part, as they both are very used to shoving me up and over things… so much so that Robyn claims the only reason she does sled drives in the gym is as practice for pushing me up things. Thanks to a busy work schedule, I didn’t actually have a lot of time to overthink (my default setting) or worry about the ride and whether it was possible.

An early start at around 8am and the light of a long May day ahead meant we’d be able to take our time and not have to rush as we tackled Glas Maol. The weather was looking perfect – warm and dry with a bit of cloud. As you would expect, from the start, it was pretty much up, up and more up. With all the views behind me, I just got my head down and got pedalling. It really was a case of putting in one revolution of the cranks after the other and, being a trike, (the Bowhead RX has two 20in wheels in the front, and a 27.5in wheel at the back) meant I had to think about where three wheels were going the whole time.

The first half of the route was relatively compact gravel, more than wide enough for the handcycle to get up. As we progressed further, and after a stop for some snacks and an in-depth discussion about why an F-15 Strike Eagle aircraft had just flown overhead, the path started to get much more challenging. We were following what were clearly well-used Land Rover tracks and they started to get quite deeply rutted. Not a problem for those on a two-wheeler, but for me the challenge was which wheels I needed to put where. The front of the handcycle was just a touch too wide to sit in the rutted tracks, the middle ground between the two tracks wasn’t quite wide enough, and putting one wheel in the track and one wheel out put the handcycle at an angle that made it near impossible to continue pedalling. This meant that a few times I had to take to the heather at the side of the tracks to look for some firmer ground.

A couple of tricky sections made for some slo-mo spills (and good photo opportunities), and needing some assistance from Robyn and Keith to get me through gave me a shoulder strain that is still niggling me six months later. (I made the typical mistake of putting my arm out to try to stop from going right over and then hearing something click in my shoulder.) It was a tough and continuous climb which proved to be much more mentally demanding than I anticipated as I constantly needed to look at where I had to put myself and the three wheels took more out of me than I’m used to when I’m carving down the ‘champagne gravel’ of Aberfoyle.

Struggle both ways

As I felt myself really start to struggle a few hours in, I asked: “How much further to the summit? Keith and Robyn simultaneously pointed to the cairn, only about 500m away. With a new burst of energy, we headed straight for the cairn and the summit of my first-ever Munro. The feeling of achievement as we reached the top was overwhelming in a rather unexpected way. I was emotional, and I was quiet (which is very much not like me) as we hugged and celebrated getting there. After we took some photos, I rode off to a section just away from everyone else and looked out at the stunning views and landscape. I needed a few moments to take in what I was seeing and what we had just done. It truly left me lost for words that I had been able to get to such a place, which for such a big part of my life I’d felt was just never going to be achievable. We did it. Technology allowed us to do it. The support of good friends around me meant we did it.

It wasn’t over, however, as we still had to come back down. The challenge then was to pay attention to the track in front of me while being faced with all the views I didn’t get to see on our way up. If anything, the way back down was much harder. The issues I had with the tracks going up were much more challenging when gravity was added to the mix. With small front wheels and limited travel in the shocks, it wasn’t the easiest to just flow back down. It was much more tense and my whole body had to work so much harder to stay upright while also choosing the right line. With sections of creeping down mixed in with sections of letting it just run and hoping for the best, I think in some ways I felt a greater sense of achievement from getting back down.

One bag limit?

So the question I’ve been asked many times is: “Do you want to do more Munros?”

Do I want to be a ‘Munro bagger’… or, as Pete decided it would be called if done on a handcycle, ‘Handbagging’? The answer is no, not really. With 281 other Munros out there, and perhaps only a handful being possible with current adaptive cycles, it’s a challenge that I hope someone else takes on when the technology allows. That being said, it’s an experience I will never forget and one that I hope others can get to experience with the help of technology, friends and the support of organisations like the Adaptive Riders Collective. For me, it was an eye-opener, a historic hurdle that I overcame and one that gives me so much confidence and enthusiasm to take on other challenges as I go forward.

For more info go to www.adaptiveriderscollective.org