We can’t pretend that mountain biking is green. Riding your bike instead of getting in a car is green, but that’s not what mountain biking is. Mountain biking is play, and activity. But by getting us out and about into nature, it can encourage us to be more green. We see the changing of the seasons, feel the impact of extreme weather events, appreciate our surroundings and what it gives us. You tend to care more about things you see, use, and benefit from. Having more people mountain biking should create more people who are healthy and happy, and also more people who care about their environment.

It could help things shift: mountain bike companies sell bikes to more people; more people mountain bike; more people care about the environment; more people put pressure on mountain bike companies to be more green. But we’re already mountain bikers, so can we help kick start this shift? Is it already happening?

The Reframing Mountain Biking event I attended last week examined issues around these themes. It’s the second one I’ve been to – the first was in 2022 and I wrote about it here. Among the people in the room then and this year, there was a sort of broad feeling that mountain biking needs to change. There’s a whole host of intertwined reasons why. More people are mountain biking, which means there’s more need for trails, which means more support is needed for trail associations and those caring for trails. Climate change means trails and the landscapes where we ride are at greater risk of damage, from heavy rains, forest fires, gales, and drought – again increasing pressure on those trying to keep trails open. And we want more people to do mountain biking, whatever their background, partly because we know it’s brilliant and why shouldn’t everyone experience it, and partly because it’s a great way to sell bikes. And then that’s more people mountain biking, which means there’s more need for trails… except there’s a chicken and egg in there, because we need trails near people if they’re going to try mountain biking. Either way, support for trails and trail access is needed… and climate change is changing how we design and maintain them. So, maybe, we also need to be looking at how we can affect climate change. Everything is connected… everything feels big. Is there actually anything that anyone can do?

You can debate whether mountain bike companies have cynically manipulated us into buying new things every few years because the old thing is now obsolete and all the new things don’t fit together with the old things. Or whether it’s an inevitability of new technology, there will always be leaps and bounds, and nothing these days is retrofittable or upgradeable, is it? Bikes are something of a last bastion of fixable and upgrade-able. Whatever the reason for the buy-new-better-bits-itis, I think we’re in the last days of running a business on the basis of selling a new and improved product every year or two to the same pool of people. Advances in product inevitably become more marginal as the technology becomes better understood, the pool of buyers becomes harder to persuade that they really need that next new thing, and sales dwindle.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

You can also debate whether mountain bike companies are cynically turning their eye to broadening the appeal of mountain biking in order to sell products the more people, or whether it’s because it’s A Good Thing. I don’t think I mind either way, because shifting the focus from selling more ‘new’ things to the same people, to selling things to more new people, has got to be better for the planet. Rather than reinventing the wheel every couple of years so we have to throw our old wheels out (and along with it the old frame that the new wheels won’t attach to), a more steady state of stable technology being sold to more people feels… sustainable-ish.

Making this shift however is going to require some structural change. The cake is not infinite. You can slice it more thinly and give ever thinner slices to more parts of a business. Or, you can give smaller slices to parts that currently get big ones, and reallocate the extras. In the last year or two, bike companies’ cakes have got a whole lot smaller. There’s less to slice in the first place. So how should they decide who gets the big chunk with all the icing, who gets a little slice, and who mops up the crumbs?

Right now, for many companies, there’s a great big slab of cake going into the elite end of things. R&D for the pointy end of mountain bike racing, factory team support, content creation and video rights, race entry fees, travel… lots of stuff that makes up the spectacle of mountain biking. It’s the tip of the iceberg – the visible bit of mountain biking that makes onto TV, into adverts, into social media. Without this visible stuff, would people know that mountain biking exists? I suspect they would – lots of people get into mountain biking because they meet someone who shows them it. Many people report that what they see of the elite/spectacle end of things makes mountain biking feel unattainable and non relatable. Bumbling around in the woods with friends feels more within the realm of possibility. Nonetheless, there is probably a place for elite racing – it’s often fun to watch, and we like following our favourite athletes. So how can bike brands make sure that some of all this highly visible scene does some good for the average rider, and for the image of mountain biking?

Broadly speaking, advocacy work – whether it be bringing new riders in to mountain biking, trail advocacy, or something else – has been the prevail of the ex-elite racer rather than the current champions. It’s a role that gets taken on once the pressure of training schedules and race calendars has been lifted. I’ve heard it said that to be a top racer, you haven’t got time to think about anything beyond the actions that are going to put you closer to the podium. But with all the content creation that goes on in this world, I find that a little hard to believe. How different could things be if brands put advocacy work at their core, rather than as a peripheral project? If the top athletes were given – and expected to give – time and space for trail work, or coaching, or counting the number of curlews in a field. How would it be if vlogs spliced sick tricks with trail cleans, or nature facts? Perhaps all that influence could be used to steer us towards positive behaviours instead of – or as well as – purchases.

Doing good stuff doesn’t have to be all worthy and weave your own kneepads. It can be about informing consumers to make greener choices – genuinely greener choices, not just ‘we’ve reduced our plastic packaging by 30% (which was easy because 50% of it was superfluous decorative tat)’. But individuals making better choices is just tickling around the edges when it comes to climate change. This is where proper structural change comes in – and where the bike industry is, I think, stuck in the past.

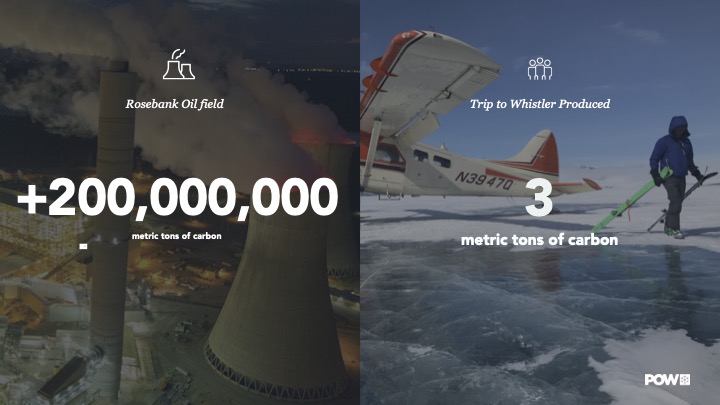

Lauren MacCallum from Protect Our Winters was one of the speakers at the Reframing Mountain Biking event, and she posted this slide:

This illustrates the huge gap between what we can do as individuals, and what can be done if there is leadership and structural change which puts climate change (or any major social change) at the centre of decisions. As a collective of outdoor enthusiasts who rely on the natural environment for enjoyment, activity, headspace, space to meet friends, we can (and should) direct our voice at those in power, and let them know that we really would prefer it if we didn’t warm the planet any more, thank you very much, and could we perhaps just leave that oil in there ground, where it is? (If you want to help make yourself heard, Protect Our Winters has a campaign you can sign).

The bike industry can do its bit too, but it needs the big players to really engage with things. Cotic has really shown what’s possible if you decide you’re focussed on doing good, as well as making bikes. Relatively speaking they’re a minnow in the bike world, but they’ve made an impact well beyond their size. They’ve supported trails, avoid plastic and reuse packaging where possible, helped all sorts of different people experience bikes and mountain biking, and are always looking at the environmental impact of their products. They’re recently announced they’re not making any more titanium bikes, partly due to their environmental impact, and they already avoid carbon wherever possible. What could happen if the giant whale sharks of the bike world took a similar approach?

Lauren told us about how, in the snowboard world, brands who were usually in competition with one another pooled their knowledge in order to bring a bio-based epoxy to market. On their own, each brand had come close to figuring out a more environmentally friendly epoxy, but together, they cracked it. Imagine if the bike industry applied the same approach to carbon fibre? There’s no getting away from the fact that carbon fibre is made from petroleum products, energy intensive to produce, almost impossible to recycle, stuck together with harmful epoxies, and sometimes difficult to repair. What if the big players in the bike world set about changing that, working together to make a less impactful carbon fibre?

The bike industry has started to examine its impact, with more and more companies producing reports that show the carbon footprint of their products, and other environmental impacts. But it’s one thing to know that you’d need to replace 430 miles (or, more likely, more) of car journeys with cycle journeys to offset your bike’s production. It’s another thing to say ‘our elite level carbon fibre bikes account for a disproportionate amount of emissions, no one is riding them to work, so we’re going to stop making them’.

Back in 2021, when Trek published what was one of the first in-depth analyses of bicycle product impact, Tom Johnstone wrote in his article for us:

“Trek has done what no other major bicycle manufacturer has done (yet) and this report represents a huge step forward in the cycling industry. That said, it cannot hide the fact that the industry is still pushing high spec, high tech, low repairability and mass consumption. Until the industry, or one of the major players, takes the bold step away from high end models and constant updating of bikes we will never get a real grip on the spiralling CO2 emissions of our sport. E-bikes need motors and batteries that are repairable in the local bike shop, roadies need reminding that a £4k bike is almost as fast as a £13k bike, but a damn site more environmentally friendly, and we all need to buy less, repair more and keep the bike we have longer.”

“Reducing the ever changing ‘improvements’ of new standards would go some way to reducing waste as riders could upgrade just the parts that need changing and reuse parts off their old bike, while making everything repairable and spares available would cut a huge amount of CO2 from the industry. Consumerism and disposability are the two greatest issues, neither of which can we cycle our way out of, and no matter how many trees you plant, keeping your current bike will always be a better option than buying a new one.”

Here in 2024, we still seem to be stuck at brands producing reports and eliminating plastic packaging. It’s perhaps understandable that no brand would take a step like stopping carbon manufacture alone, making them an outlier in the industry. Having said that, Trek has just announced it’ll be reducing its SKUs (Stock keeping units – basically the number of different bikes, across models, specs and colours) by 40%. Perhaps there’s an opportunity there to weight the full in favour of the bikes that are least bad for the environment?

But what about if elite level sport helped make it happen? What if there was a ‘no carbon wheels’ rule introduced at World Series level? What if Crankworx had a category only open to metal bikes? What if entry fees (or points) for teams were weighted according to the environmental impact of their equipment and procedures? There are many opportunities for incentivising innovation in less impactful participation in mountain biking. It’s often said that elite level competition gives us the trickle down technological advances, so why not measure those advances in environmental terms? Who will lead the charge?

Bike industry, we’re looking at you. The next big leap is not wireless brakes, or a new suspension kinematic. The next big leap is mountain bike technology that doesn’t cost the earth.