A custom-built bike is a dream for many, but how hard is it to choose (and then live with) your exact, perfect machine?

Words As told to Chipps Photography Credited

For some people, commissioning and speccing a custom-built bike is a fantasy indulgence, for others, it’s a necessity, and for others still, it’s a regular splurge. Judging by the crowds at shows like Bespoked, you’d think that everyone was lining up to get a frame built. And while there are many builders toiling away in sheds around the UK, the reality is that custom frame numbers are in the hundreds per year rather than thousands. In fact, Heritage Crafts – the national charity for traditional heritage crafts – recently downgraded ‘bicycle frame making’ from ‘Viable’ to ‘Endangered’ in the UK along with harp making and letterpress printing.

For this feature, I talked to a few owners of custom bikes to find out their motivations behind going custom and to see if it really is the pinnacle of artisan bicycle design, or just a vanity purchase that’ll quickly saddle you with quirky, rapidly dating ideas and a gopping paint job.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

But why?

The biggest question isn’t actually ‘Should you go custom?’ That’s down to the individual, their budget, riding and outlook. If you want a custom anything, and you can afford it, then I don’t see why you shouldn’t. The most important question, though, is going to be ‘Why?’ – and this is where you have to be honest with yourself.

A custom frame can be a great present to yourself, but when ordering it, you need to work out what issues it needs to solve. Extra tall and short riders are the most obvious candidates for custom frames, as getting a bike to fit correctly at the extremes of sizing can be tough and limited (though not impossible). For those of us in the squishy middle of the bell curve, there are still many reasons for going custom.

Custom geometry and non-standard components seem to be the main drivers for other custom frame customers. Faced with an ever-increasingly competent selection of production bikes, there are still, somehow, riders who can’t quite find what they want in an off-the-shelf frame. Extremes of geometry can often be catered for by a sympathetic framebuilder and, indeed, the experiments that work for one-off frames can sometimes filter back into production frame ideas. The ones that don’t, though, are never heard of again.

Reynolds Tubing credits small builders for helping push bike geometry and for requesting oddball tube lengths and diameters to facilitate progressive geometries that bigger companies can benefit from. Small custom builders, too, can be early in the adoption of new technology and standards, like Pinion gearboxes, belt drives, flat mount brakes and headset standards. Even going back to 2002, Dave Yates built stems for the previously unheard-of Aheadset threadless steerer concept, a year or so before the component companies caught up.

Write your own story

Everyone has an idea of their perfect bike, don’t they? And sometimes those things can’t be found on the shop floor, so a custom-built frame, made just for you, to your measurements and spec can be just the thing. And for the last decade or so, there were framebuilding courses popping up that would help you build your own if you had the time, money and patience to spend a week or more in someone else’s workshop to be shown the pointy end of hole saws and files, hopefully emerging with a frame that you had designed and hand-built yourself.

Many of these courses, like Frome’s Bicycle Academy or Kent’s Downland Cycles, have closed down in the last couple of years. These courses would often be the place where the more bonkers ideas emerged; if you’re the framebuilder AND the customer, surely you can make what you want? However, even so, the course tutor would often steer the more unusable ideas towards something that might eventually work.

What! I have how many custom bikes?

In writing this, I discovered to my shock that I’d commissioned, built or been involved in at least ten custom bikes for myself over the last 35 years. I still ride seven of them, but over the years I’ve discovered that there are some decisions made at the time that haven’t aged well. Ironically, it’s the more modern bikes that have aged a little quicker.

For the first half of modern mountain biking’s history, change was slow: wheels were 100/135mm and quick release. Brakes on the 26in wheels were on the rim, gears were 3×7, 3×8 or 3×9… In the tens and teens, we had an explosion of progress that mirrored that of consumer gadgets like cameras, computers and phones. Next year’s product was likely to be twice as good as this year’s, be backwards incompatible and (inexplicably) cost exactly the same. So, 135mm dropouts became 142mm, 142 quickly became 148mm and then (occasionally) 157mm… 26in became 27.5in OR 29in and then became 27.5 AND 29in or 29in. Geometry became both slacker (head angles) and steeper (seat angles). The saddle to bars distance didn’t change much, but top tubes became longer while stems became shorter. It was hard to keep up, and custom bikes from this era are equally likely to be comedically out of date as they are to have prophetic geometry stemming from an educated guess at the time.

‘Build it around this seat quick release please!’

If you’re after a custom bike because you want up to the moment geometry or a particular component spec, then it’s going to be a little like ordering a new laptop, digital camera, or smart TV. There’s never going to be a ‘perfect’ time, as the technology is likely to move too quickly. Your state-of-the-art bike will, at best, be contemporary for a while – until the next UDH-compatible derailleur comes out, making your Paragon Machine Works sliding dropouts a sad reminder of mechs gone by.

From my own experience, fixating on a particular component can get you into trouble – or equally can be the basis for a beautiful, unique bike that remains special to you for your whole life.

Beyond geometry quirks, one common and divisive choice in custom bikes is the single-speed. It’s something that, arguably is wonderfully served by a custom builder, there being scant few production single-speed bikes. But in ten years’ time, will your ageing knees still thank you? Will you still live in terrain that’ll accommodate a one-speed bike? Who knows? But it’s something to bear in mind as it’s one thing that’s hard to buy, or upgrade your way out of.

Other component choices can be similarly limiting: dedicated braze-ons for hub gears or deciding to skip any gear bosses as you’ve gone fully wireless are bold moves – and will tie you into a particular system. Even range-topping components get superseded sooner or later. XTR Di2 came out in 2015 and hasn’t been updated since. You could have a six- or seven-year-old bike dedicated to this standard, only to find that it hasn’t improved since then. Even SRAM, the wireless pioneers, upgraded Eagle AXS to Transmission. If you want a contemporary SRAM groupset and you have a three-year-old state-of-the-art custom bike, tough luck. Unless you had it specced for the UDH dropout at the time, there’s nothing, short of a cut-and-shut rebuild that’ll bring your once state-of-the-art machine up to date.

Don’t buy to sell

One other constant is that anything and everything that you hold dear, or valuable, on a particular bike or build, is very, very unlikely to resonate with a potential second-hand buyer. Your favourite colour is yours alone. If you have the stem painted at great expense, it won’t add a penny to the resale value over a black one – the same for carved seat lugs, pump pegs and diamond-shaped reinforcements around the bottle bosses. If you like them, then have them, but as you go through the list of added extras, know that they’re for your benefit and any upgrades won’t add to the resale value.

Jon Kolon of Dharma Wheels Cyclery in Park City has steered many customers away from fancy components in favour of simpler ones for 30 years:

“When you are a custom bicycle person, you let it go and trust in the experience of the shop and the builder to create something that is specific to your desires and expectations. All of my high-end customers have multiple bikes so I tell them to worry about changing standards and geometry with those less expensive ones. Your custom bicycle is uniquely created for a specific purpose – and it does not have to follow any trends. Believe it or not, I sell a lot of high-end custom frames with rather basic components. And then people save up and come back for another bike for a different specific purpose. I can’t tell you how many locals ride 20+-year-old easily maintained custom bikes that I’ve sold them that get ribbed on the trail about 1-1/8in headsets, quick release wheels or alloy rims by riders who don’t know who Chris King is. My people tend to just smile and nod, saying “Yeah, I hear what you’re saying but I’ll never sell this bike.”

Pick your builder

Commercial builders have to make a living. In order to do that, they either need to build a reputation, or rely on and maintain one. Not all builders will relish your revolutionary ideas, and more established builders may not even need that kind of hassle. As Joe from Starling Cycles puts it: “I think what you find is that the more experienced a framebuilder is, the fewer options they will offer and the more they will try to steer the customer.

“Maybe once a month I get sent a CAD model by some kid, or enthusiastic retired chap asking me to build their weird design. ‘Yes, but it will be £25,000’, is my standard reply. ‘Why?’ they reply. Because nothing you have drawn is actually manufacturable, it will need a total redesign. Then we’d need a whole set of new tooling to build the swingarm. Then there’s all the machined parts you have created, one-offs will be around £1,000 each, at least. Then you need to divert my workforce from building profitable bikes for three weeks to get it done. Finally, it will be shit and you will blame me!”

Joe continues: “In reality, I’d say custom sizing and bikes are mostly for people who think they are special. They think they are different to other people and, therefore, have specific requirements. It is rarely true, so I try very hard to push back onto standard bikes. The custom aspect only adds cost and actually risks moving outside our experience of what makes a good bike. A classic example is that they need a 62° head angle and 500mm reach (for a short rider). From experience of building these types of bikes, I know that unless you are a very good and very strong rider (which mostly likely you aren’t), you won’t be able to make this work, even then it probably won’t make you faster.”

Talk, make notes, distil

Once again, I’ll restate that wanting a custom bike is a valid reason in itself but do be prepared to do some honest thinking about what and why you want it. Have a long, hard think about what you want this bike to do that isn’t served by production bikes. If you just want a shiny bike from a custom builder, admit it to yourself. If you want it to do something specific, talk to the builder and make sure you’re both on the same page.

Think carefully about overly ‘progressive’ geometry, or quirky components. If Sturmey-Archer stopped making hub brakes tomorrow, would you be left with options? If Shimano came out with a new dropout-specific rear mech, would you be able (or even want to) upgrade to it with the design you’re proposing?

Know that any custom appointments you make on the frame are for your pleasure only. Don’t expect any other rider to think the same as you. Resale values on custom bikes are generally poor because no one is quite like you.

Talk to the builder. Your custom framebuilder has built more bikes than you have. They build bikes every day. They have heard every crazy idea out there. You are unlikely to be the first person with your progressive geometry idea. If you are set on a 58° head angle, explain to your builder why you’re convinced by it and want it on your ‘forever’ bike. If you’ve bought a stunning new hub with an unconventional axle dimension, see what your builder thinks of the idea. If your pioneering hub explodes in a year and a day, do you have alternatives?

Have a think about where you see yourself and your bike in ten years’ time. Will you regret going for a flipflop, fixed/freewheel hub, dirt oval, cycle speedway-style bike with Lauf forks and a clear-over-rust finish? Or will that dull but sensible steel hardtail with ‘vanilla’ Shimano XT components still appeal due to the craftsmanship of the welds and that particular one-off purple metal flake paint job that only you appreciate?

In summary

If you want a custom-built, go for it. Have a good chat with yourself. If it’s a vanity project, embrace it. If it’s a pioneering geometry experiment, then find a sympathetic builder who’ll make it for you. Or be guided by an experienced builder who’ll steer you away from making something terrible with their name on. Remember, all of those terrible misspelled tattoo memes? A signwriter or tattoo artist will make what they’re asked to – it’s up to you to check and double-check that you’ve not accidentally ordered 20in wheels, or that your 500 emails to the builder haven’t contained six conflicting top tube lengths.

Take your time. Your new bike won’t be built the week after you order it, so why rush in the planning of it? Talk to builders and other existing owners, and scour the internet to see what might work for you. Choose components with open eyes. Think about how long you’ll be able to get spares, or how committing your retro axle-standard or spacing is going to be in ten years.

It’s a bike for life. Even if in ten years it’ll only get used for fetching pizza from town. Pour your soul into it but don’t get carried away – unless that’s the whole point of the build. At the end of the day, your builder will likely build what you ask, but make sure you both know what you’re expecting of one another.

And then ride it. Ride the snot out of it.

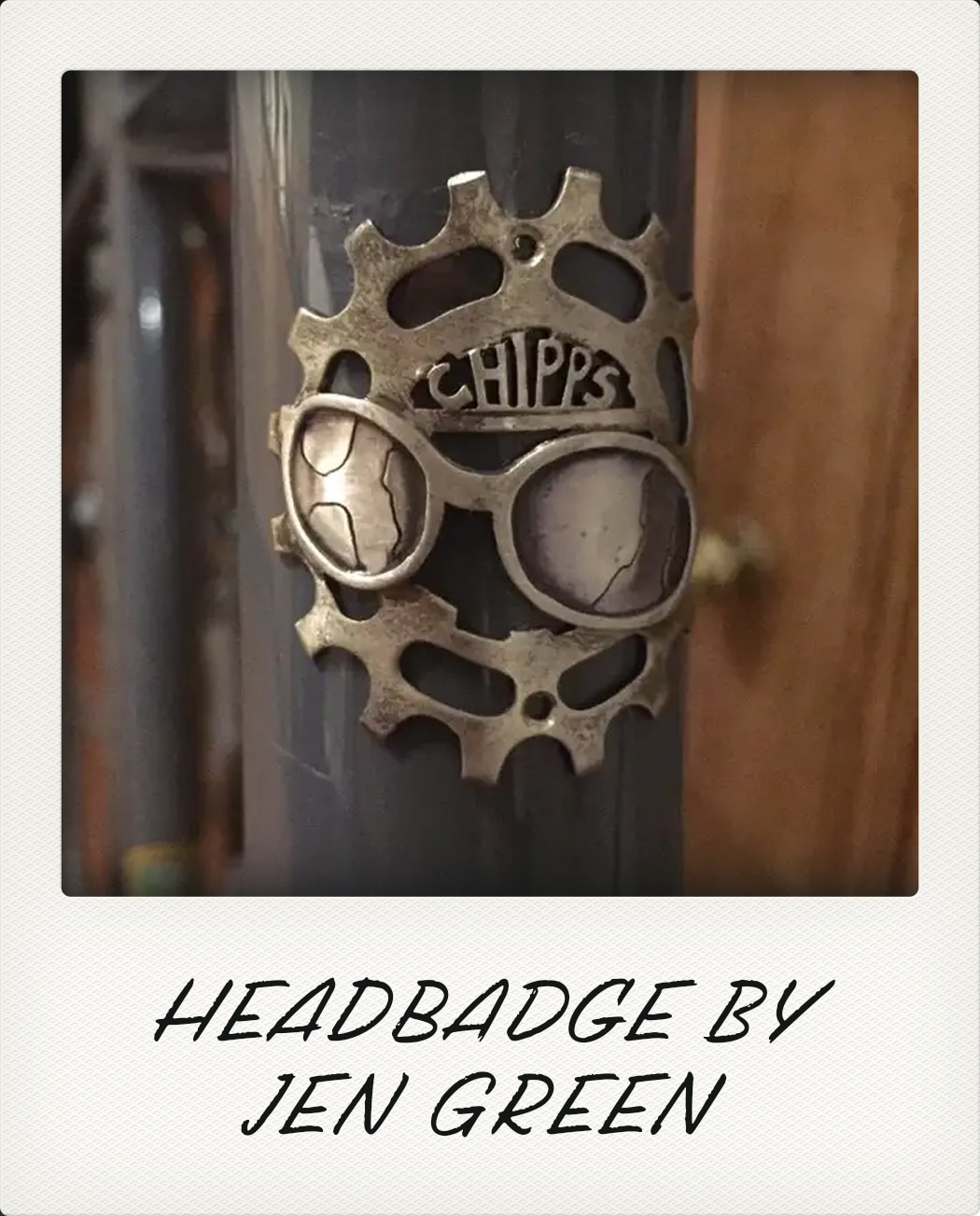

- Owner Name: Chipps

- Bike Builder: me (built on a Downland Cycles course)

- Frame/Bike name (if there is one): The Performance Pub Bike

- Year Built: er… 2017?

- Price Paid (unless it’s a sore point): Can’t remember.

- Was there a special or specific occasion that prompted this purchase? I wanted to go on a framebuilding course and had to think about what to build.

- Was a custom bike on your shopping list, or was this a last resort as no production bike fitted your needs, spec or frame sizing? I had to choose what kind of bike to build and, rather than end up with a halfhearted Cotic Soul copy, I figured I’d go full custom and design a bike that no one else actually makes

- How did you choose a builder? There weren’t many framebuilding courses in the UK. There are even fewer now.

- What was your ‘use case’ or specification? I wanted a bike designed to go to the pub (or the shops, but mostly the pub) and back. It only needed three gears (down the hill, along the canal to the pub, back uphill home) and brakes didn’t need to be massively powerful. It did need to be low maintenance (and stealthy looking too).

- Do you use it all the time, or is it kept ‘for best’? It was my daily commuter for a couple of years.

- Have you had to make any changes? I changed from ‘North Road’ bars to ‘vicar’ bars. That’s been it.

- Does it do what you hoped? Yes

- Any disappointing elements? (See Q.10 too)

- Anything you’d do differently with hindsight? I might consider some more common components… but at the moment it’s fine.

- Were there any quirky or ‘innovative’ design cues you made that you now regret? (Such as building the frame around a specific component, axle standard, frame bag or specific use?)I chose 27.5in wheels and Sturmey Archer three speed hubs and hub brakes. However, it turns out that the hubs are only 36H and I was VERY limited in my choice of 27.5in x 36H rims. One set of Mavics.

- Did you include any features that were innovative at the time but now fairly standard/widely available? Not really, no.

- For contrast, are there any features you included that are now obsolete? I’m limited to Sturmey Archer gears and brakes, but they’ve been around 100 years, so I should be OK for spares. In fact, I just broke a gear widget inside the hub. The parts are available, as are complete replacement hub internals for not much cash.

- Is it as easy to live with as an off the peg bike? Beyond the ‘Built just for me’ halo, is it actually any better than a production bike?I probably could have got a Pashley or restored a 1960s bike, but this works fine for me.

- What choice did you agonise over most? Where to place the downtube three speed shifter

- Are you bored of your custom paint job yet?! It’s (Orange Bikes…) Norlando Grey, it’s fine.

- (If you’ve had it a long time) Do you feel any conflict between keeping your bespoke once-perfect bike, and the temptation to move with the times and take advantage of new standards or technology? This should last a lifetime of pub going… I’m happy.

- Owner Name: Jeff Lockwood

- Independent Fabrication Ti Deluxe

- Year Built: 2005

Was there a special or specific occasion that prompted this purchase? I had a unique opportunity to get this bike, so I jumped at it.

Was a custom bike on your shopping list, or was this a last resort as no production bike fitted your needs, spec or frame sizing? It never entered my mind. Especially a titanium frame!

How did you choose a builder? I always had a soft spot for IF. They were an East Coast company. I knew some people who worked there, I loved the attitude of the brand, and the bikes were sexy as hell.

What was your ‘use case’ or specification? I wanted a titanium single-speed made to rip the rooty, rocky, and twisty East Coast singletrack.

Do you use it all the time, or is it kept ‘for best’? It’s been sitting in my parents’ basement collecting dust since at least 2016. It’s a 26in mountain bike. Plus, I live about 3,178 miles from my parents. And I broke the faceplate on the stem when I last rode it in 2016. So, no, I don’t ride it anymore. But this summer, I cleaned it up really well, bought new tyres, and got a new bar, stem, post and saddle for it and gave it to a friend who was looking for a bike for simple, short mountain bike rides and riding around the campus where she works.

Have you had to make any changes? Nope.

Does it do what you hoped? It absolutely did. I rode that bike all over the United States and loved it. But it was an absolute dream to ride the amazing trails at the Belmont Plateau in Philadelphia. That is stuff I made this bike for. It is agile to the point I think it’s telepathic, sucks up the bumps and is lightweight.

Any disappointing elements? (See Q.10 too) Yes, 26in wheels. For some stupid reason, I wasn’t reading the tea leaves correctly and/or I was not yet a fan or believer of 29ers… despite working for a mountain bike magazine. If it had proper size wheels now, I’d absolutely still be riding it.

Were there any quirky or ‘innovative’ design cues you made that you now regret? In retrospect, and what I know now, I’d maybe have gone with sliding dropouts rather than an EBB. This was also an early-ish disc brake bike, and sliding dropouts then might not have played so nice with disc brakes. But the EBB would hardly be a dealbreaker even now.

Did you include any features that were innovative at the time but are now fairly standard/widely available? Not really.

For contrast, are there any features you included that are now obsolete? Wheel size. Geometry might be different now, as it kind of looks funny these days. However, I would not change anything with the geo if I did it again, assuming I still planned to ride it where I originally intended. OK, yes, 29in wheels will change the geometry, but aside from the wheels and maybe the BB, that’s all I would change. I don’t care if the stem looks dorkily long now. Bike trends might have changed, but those trails at the Belmont have not.

Is it as easy to live with as an off-the-peg bike? Beyond the ‘Built just for me’ halo, is it actually any better than a production bike? I believe any number of stock bikes would have been just as enjoyable in the Belmont… and I have ridden a lot of them. And I certainly enjoyed the hell out of them. However, having a frame made to my spec and with a rather unobtainable material… that certainly ups the awesome factor. But would I have been sad to ‘go back’ to a stock bike to ride in there? Absolutely not.

What choice did you agonise over most? I was concerned about geometry. I referenced other bikes I liked and owned, explained what I wanted and where I wanted to ride it. The minds at IF were familiar with the terrain and knew how to distil my geo thoughts and examples. It, of course, worked out.

Are you bored of your custom paint job yet?! Hell no! There’s no paint! Ti should NEVER be painted.

Do you feel any conflict between keeping your bespoke once-perfect bike, and the temptation to move with the times and take advantage of new standards or technology? If I’d specced it 29in, I’d have it with me here, today.

- Owner Name: Jon Meredith

- Bike Builder: Dawley Bikes

- Frame/Bike name (if there is one): Eponym custom

- Year Built: 2023

- Price Paid (unless it’s a sore point): £1,020

Was there a special or specific occasion that prompted this purchase? No – I have a frame Thom built a little while ago that is less evolved along the direction I am keen to explore with bicycle geometry – this was the next step.

Was a custom bike on your shopping list, or was this a last resort as no production bike fitted your needs, spec or frame sizing? Absolutely – it would not be possible to achieve this without a custom build.

How did you choose a builder? The previous frame built by Thom is fantastic and he was a pleasure to deal with in all aspects from advice, informing me of how things were going all the way through to delivery.

What was your ‘use case’ or specification? I have been pursuing a specific geometry for a few years now – longer wheelbase, steeper seat angles than the traditional hardtails of the 2010+ but avoiding an overly slack front end. Front-end trail (or mechanical trail) and flop have been the factors that I am most interested in now that my contact points and favoured length (rear and front centre) have settled. In essence, I have been trying to steepen the head angle from a known point of weight distribution over the front contact point. In order to achieve this, stem length has had to shorten so that the real reach from saddle to grip can stay within the range I find ideal. Once you go under 32mm stem length, things get interesting! This bike was born as a package once I had a one-piece bar/stem in hand that is equivalent to a 15mm stem. The rest of the geometry could be set thereafter.

Does it do what you hoped? Yes – the reduced flop is a game-changer. Slack head tubes work on downward-orientated trails very well, but the reality of a ‘messing around in the UK bike’ is that there is much more ‘along and up’ – at least for the riding I like to do. Achieving a reasonable trail, good stability with a long-ish front centre (800mm in this case) and keeping flop low requires a steeper head angle than is zeitgeist – 68°//DEG// in this case. There is a real interplay between all the geometric components – stack and reach do not tell you enough and it has been fun to push things a bit and the results are just what I was looking to do. The bike is incredibly responsive while retaining stability and assuredness on rough or steep trails.

Anything you’d do differently with hindsight? Well, full disclosure, Thom is building V3 soon that goes steeper, longer f-c and even less flop. Again, the bar/stem was critical in achieving this. How far is too far to push? We’ll see!

Were there any quirky or ‘innovative’ design cues you made that you now regret? No – everything was a known entity. I have in the past used standards and components that were custom or rare and in general have had good luck – but the commitment requires careful consideration.

Did you include any features that were innovative at the time but are now fairly standard/widely available? That’s tricky to reply to – the geometry is the innovative feature and it isn’t widely available without a custom build. It is designed and optimised for 29×2.4in rear/29x3in front tyres – which seem to be a little less available than previously, though I have a stockpile!

Is it as easy to live with as an off-the-peg bike? Beyond the ‘Built just for me’ halo, is it actually any better than a production bike? Absolutely, nothing has been difficult in any way with this bike. All components other than the frame/stem/bar are standard and widely available and I believe that bikes will evolve this way in time.

What choice did you agonise over most? Whether to commit to a one-piece bar/stem. This was the crux that allowed the rest of the bike – but once you are in there’s no adjustment so everything needs to be bang on before the metal is melted together.

Are you bored of your custom paint job yet? No! I went with utilitarian grey highlighted by some bright ano from Bentley Components!

Do you feel any conflict between keeping your bespoke once-perfect bike, and the temptation to move with the times and take advantage of new standards or technology? Not much – I tend to ride several bikes concurrently and enjoy the comparing and contrasting elements. I am looking forward to trying the next one too!

- Owner: Si Trickett

- Curtis Bikes

- Frame/Bike: ADV9 29er Adventure Bike

- Year Built: 2022

- Price Paid: c.£2k (frame only, it has lots of bosses! as they were £25 a pair). Think given the effort involved is actually a bit cheap.

Was there a special or specific occasion that prompted this purchase? Just years of testing, building and buying various bikes just trying to get the right bike.

Was a custom bike on your shopping list, or was this a last resort as no production bike fitted your needs, spec or frame sizing? As I am borderline freakishly tall (6ft 5in), getting the right size and what I had decided I needed in terms of spec, custom was the only option.

How did you choose a builder? This was the hardest part; many custom builders say they offer ‘custom’ bikes, but that in reality means either adapting one of their existing designs to fit a certain size person, or they have a particular style of frame and if what you want does not align with that, then they are not interested in building. In the end, after talking to five or more builders, I initially took a risk on a young new bike builder as he was interested and excited about what I wanted building. Had a great bike fit done and the build started, but unfortunately, he ran into an issue during the build and it made me a bit nervous so we decided not to continue, felt bad as think it has all been exciting for both of us, especially as I think I was his first external customer, but if you are looking for a ‘forever bike’ a problem at the build stage is quite off-putting. Gary at Curtis was keen to help, though Curtis is known for certain types of bikes that have a particular style, so there was a bit of concern as to whether such a build of mine would fit with that image. But with a bit of persuasion and the fact that Gary is a thoroughly lovely chap it was booked in and then in the build queue (which was about 3–4 months).

What was your ‘use case’ or specification? I had a Jeff Jones LWB and this was a fab bike, but was just not quite big enough and had some odd quirks. I sold it but missed it. So I decided to base my custom bike around that Jones, but a larger version with the quirks corrected. I used a Jones unicrown fork, as such a comfy fork and has all the bosses for racks. Forks again seem to be an issue for many custom builders.

Do you use it all the time, or is it kept ‘for best’? I use it for anything that isn’t a full-on ‘full sus’ type ride, so basically anything else, be it a towpath ride from Woking to Bath, local adventure ride, bimble around the woods, off-road tour, or an overnight off-road ride to the coast. Basically, anything off-road and might need to carry some stuff. I added lots of bosses to give as much future flexibility to fit racks, frame bags, etc. Hoping to get back to Iceland to do some more touring there.

Have you had to make any changes? Only change bars from Jones Bend to Jones Loop bars.

Does it do what you hoped? Yes!

Anything you’d do differently with hindsight? When builders are building something that is outside their norm it is really important to specify very clearly what you want. I would have liked a fraction more rear tyre clearance, but it works fine and if I really wanted to, Gary could add a little mod in the future given the nature of the fillet brazed steel frame.

Were there any quirky or ‘innovative’ design cues you made that you now regret? No. It makes use of all the current specs, internal dropper, Boost rear, fat bike front, big discs.

Did you include any features that were innovative at the time but are now fairly standard/widely available? It has so many bosses, so pretty much anything you can fix to a bike can be fixed to it.

For contrast, are there any features you included that are now obsolete? It fits [6ft 5in] me, it has a super-high front end and is comfortable to ride for very long off-road rides and it is very capable off-road and nice even on the tarmac.

What choice did you agonise over most? Where to put the bosses!

Are you bored of your custom paint job yet?! Wanted a low-key look, so it just has the Curtis head badge and no decal. Gary suggested a really nice black powder coat; had the forks done to match. Sound daft, as black is black right? But this has a really deep black look and is very nice.

Do you feel any conflict between keeping your bespoke once-perfect bike, and the temptation to move with the times and take advantage of new standards or technology? It makes use of all the current standards so should be fine for years to come. Just in the process of getting some custom frame bags made. And might go back to a hub dynamo which was on my Jones and previous bikes – at least on this bike there is fitting for cabling on the frame!