Petor recalls a simpler, damper, mouldier time measured in meals and miles, not hours and minutes.

Words & Photography Petor Georgallou

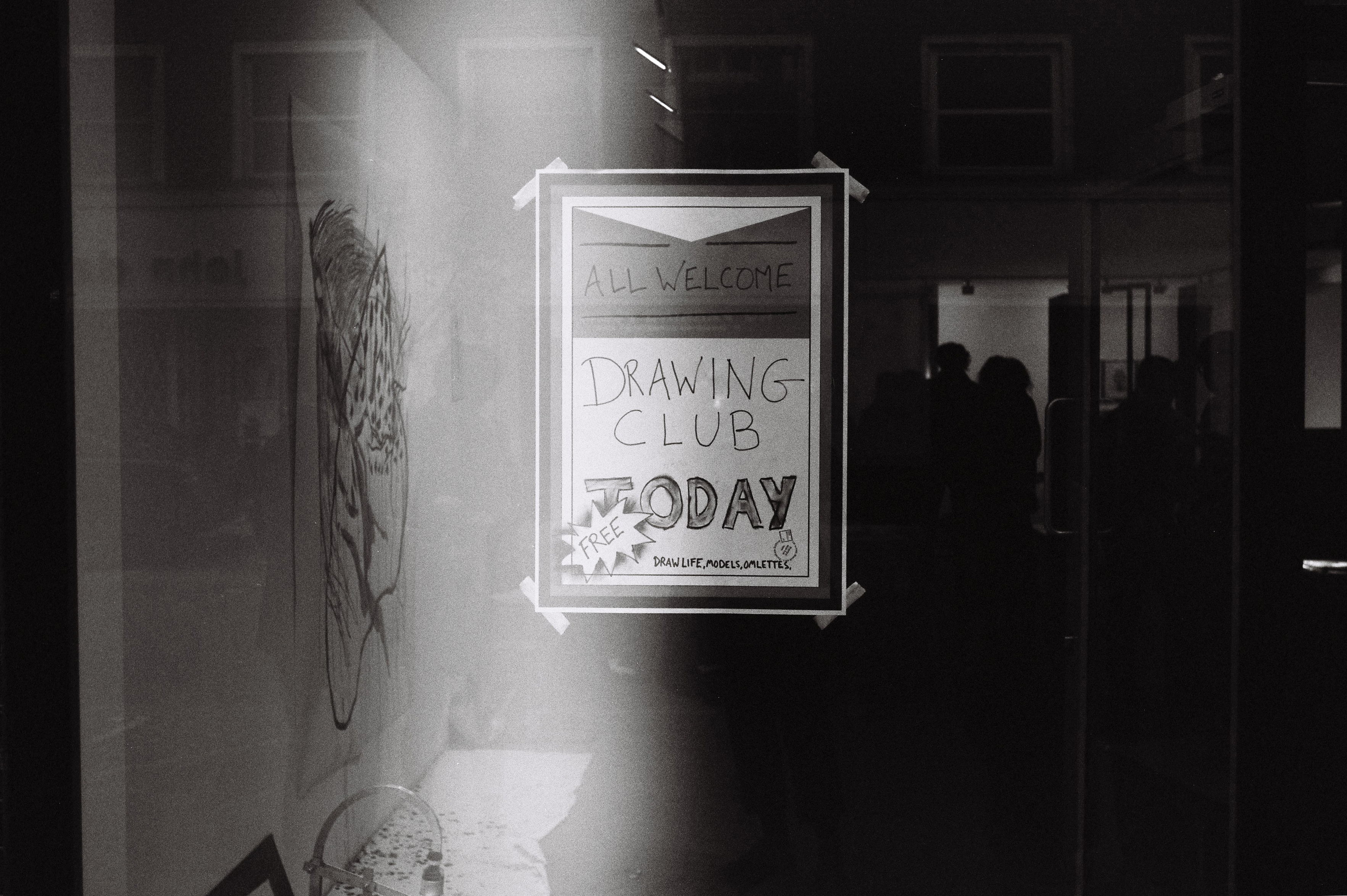

Until my MA degree, I didn’t have an email address, because I didn’t really use the internet – I didn’t really see its function. To me it seemed the ultimate luxury. I didn’t really have any money because I spent all my time in the studio painting, or tinkering, or reading magazines. Or looking at pictures, visiting galleries, listening to music and riding my bike. I got a summer job leading cycle tours for a weirdo ‘environmental’ charity. We’d cycle from town to town, performing a play to bemused school children about how switching off the lights, eating less meat and using reusable food and drinks containers would help save the planet. I’m 100% confident now that there’s no saving the planet, but as we slide off the precipice I feel better knowing I tried. My summers earning £50 per week as a stipend weren’t completely wasted because one year I managed to ride LEJOG (Land’s End to John O’Groats) three times.

Roving dads

Land’s End in Cornwall is (more or less) the most south-westerly point in England and John O’Groats is pretty much the most north-easterly bit of Scotland, so it’s widely accepted as the longest one-way journey you can make in one continuous direction in the UK. It’s the sort of cycle touring that used to happen in the 1990s and 2000s before people started saying things like ‘bikepacking’ and ‘adventure cycling’. It landed in an odd period between the Rough-Stuff Fellowship’s numbers dwindling to nothing and Surly being imported to the UK in significant numbers. While aluminium was the mainstream, traditional steel tourers such as the Dawes Galaxy could still be purchased on a high street, although discerning tourists would covet a Thorn Raven. I was not a discerning tourist, and I definitely wasn’t going to squeeze a Thorn out of my student loan.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

Somehow in my mind LEJOG is a ride ridden exclusively by packs of roving dads, clad in faded purple and teal Hi-Tec raincoats from the ’90s, knackered white Reebok classics awkwardly wedged into plastic toe clips. Needless to say, it was the ride for me! The first LEJOG was a recce. A masochistic solo slog for 11 days on a road bike. It was nice. Well, perhaps it was more OK than nice. Not seeing an interior for a couple of weeks felt good, but unremarkable. The next go was four weeks with a group of 19 strangers between the ages of 18 and 27. The weeks went by happily enough. We met people, left people and forgot people. The rolling hills set our pace and it was largely uneventful. The third go was different. Instead of preaching to kids, we helped people. We looked for people who had projects based loosely on the idea of sustainability, who had fewer than five employees and who needed help on a short-term project. We spent time. I think the tour was around three months. It was planned through word of mouth, phone calls and paper maps. The internet existed – I just didn’t know how to use it. But anyway smartphones weren’t a thing then, which meant that on the road the internet was of limited use.

Rot and rust

This was the best tour. Perhaps my favourite tour ever. It was the end of the summer, and it was getting cold. We’d planned some unpaved sections, and having ridden an approximation of the route before, I had some idea that my fancy Colnago Mexico wasn’t the bike to do it on… I’d budgeted £200 for gear and £100 per month for the trip and, having done it before, I had some idea of what I’d need based on my own experience of the specific route, rather than the ideology of a cycle tour.

I bought a used Dawes Horizon – the low budget version of the famous Galaxy, which was about as inexpensive a touring bike as I could get my hands on at £30. I bought two wool suits and a hat from a charity shop for £10, some new cleats for £10, a cheap Opinel pocket knife, a Crank Brothers multitool (which was expensive at £20, but super cheap as I still have it), and spent the rest on a budget ‘waterproof’ jacket, and making a few repairs to the bike before we set off.

Three months was ideal. We met permaculture smallholders and built fruit nets for scientists using small-scale cattle farming to increase biodiversity and trap atmospheric carbon in soil. We climbed wind turbines and learned about hydrogen fires and submarine batteries, but most importantly we were time rich and money poor. Not one of us had any semblance of appropriate equipment – our seven-speed racers and janky, low-grade mountain bikes were falling apart, frames straining and twisting under the load. We begged, borrowed and bartered, with bike shops, bartenders and tube benders.

Farmers gave us vegetables – we were vegan (except for the road kill), because we were broke and also because we cooked and ate together. We were constantly fixing everything. Mould and moths ate our clothes, because we were always wet. We always stank, even when we washed! Everything rotted in the fermenting warmth of wet panniers, and developed a very particular aroma that can be associated only with cycle touring. Something like second-hand cauliflower curry, soggy oatcakes and thick puddle water. Shoes were always the weak link; no matter how much shoe goo and pound shop gaffer tape we adorned them with. String, glue and rubber bands, unduly ‘edgy’ campfire haircuts and heated debates on hygiene (or the lack thereof) and its effect on bowel movements. We lived like kings! Or peasants? Everything we needed we had. Because everything was constantly falling apart, we became fluent in repair. The nightly repairs were our TV. Nothing was new, because nothing new would work. Anything new would be utterly incompatible with our rot and our rust and our time-stained, weather-darned, wretched splendour.

The best food I ever ate

Our accommodation hook-up fell through at the last minute… we were sodden from sleeping in a patch of trees between two dual carriageways the night before. A last-minute friend of a friend came through with an empty farmhouse. It was on top of a hill and we spent a long wet day climbing it in wind and hail. I found a pheasant on the floor that morning. We tied it to a pannier to carry it with us to mature in flavour. We arrived to find a kitchen furnished with a plucking chair on the flagstone floor and a basket in one corner. There was a tin of prunes in a cupboard, and we had half a bottle of port and two potatoes from dinner two days before. I plucked the pheasant and roasted it with the prunes, prune juice, potatoes and port. The tiny portions shared at a candle-lit table by a fire surrounded by steaming Gore-Tex, each one of us having had the first hot shower in weeks, felt like the most decadent and luxurious meal of my life. We dressed up (as best we could). We were clean, but wearing stinking wool suits newly adorned with feathers from dinner while the storm beat on the windows and doors.

The not spending of money became a game. ‘I’ll swap you a joke for that postcard’ or ‘It says here your pastries are fresh every day, do you have any of yesterday’s pastries left?’ We were a nightmare. Every minute of every day was spent waking up, cooking, eating, washing, riding, bartering, mending our junk, trying to find our destination for the night and either assembling or disassembling mouldy tents.

At some point my frame snapped at the junction of the head tube and top tube, so while everyone else headed to our camp for the night I walked off with £10 hoping to find a repair somehow. I can’t really remember where this happened… probably somewhere only semi-rural in Wales. I found a pub with a tiny door that I had to stoop to walk through, dragging my soggy panniers. A guy sitting at a decrepit three-stool bar bought me a pint of porter and half an hour later my failed frame had become a community problem-solving exercise. Dave was ringing Andy the farmer who called the local garage which was shut. Garry called his wife’s cousin who was a carpenter who knew a blacksmith who called the mechanic from the garage who had a welder in his barn and three hours later I was heading out from Steve’s barn wired from eight cups of hot sugary tea, my Royal Mail halogen-bulbed light flickering into the wet night-time.

The cost of living

Having enjoyed that freedom to engage with the world it now feels so odd to carry a device in my pocket that actively prohibits this sort of interaction. I seriously doubt I’d ever tour on such a shonky bike again, but in today’s money an exciting evening with fun strangers would look like a cab ride to the sleeping spot and probably trying to buy a new frame in the morning to swap parts onto. Modernity and comfort are the enemies of adventure and excitement. This isn’t to say that I haven’t woken up with a sore back having camped in a ploughed field due to poor planning and lack of access to information, or that I’ve never spent all night riding around in the dark with no idea where I am. Those aren’t fond memories. It’s been a decade since then and I still can’t romanticise those experiences. What I do feel, though, in my day-to-day life, is nostalgia for the clarity of thought and sense of purpose that low-grade, disorganised cycle touring afforded me.

It gave me the mental space that I needed to paint and draw and tinker and ride in a way that I probably won’t ever be able to do again. It gave me energy I needed to be creative and to be excited about the mundane and ordinary. Holding the sum of the world’s knowledge in a tiny computer in my pocket all the time has definitely detracted from the fun of old-fashioned cycle touring. To a greater extent, the experience has been tainted by my lack of time. The older you get the higher the percentage of remaining time each minute costs, and building bicycles – as I did – is an expensive way to spend those minutes. It is less efficient at generating currency than being a dentist or a hedge fund manager and, therefore, reduces the possibility of cycle touring, which reduces the possibility of painting and tinkering and thinking and chatting to strangers about whether or not top tubes can be made from tanalised 2×4 timbers. From discussions about ‘the lost coefficient of time’ or why ducks are better in smallholdings than chickens. There’s a luxury in being a full-time creative practitioner working in any medium; however, the greatest luxury is to be a full-time practitioner in living.

Living is tricky at best, but I feel like cycle touring is a pretty good approximation. It’s a way to propagate ideas, to find snippets of thought and link them together. A way to understand your own ‘machine’. To contemplate what is ‘I’ and what do ‘I’ do, and why? It’s a platform for variety that helps relate one thing to another. Time is all we have. We probably don’t have as much as we think and some of that is spent sleeping and some of that is spent cleaning toilets. Some time is spent looking at paintings and sniffing chemicals in darkrooms. The lowest grade of time is spent degrading ourselves in the aim of appeasing the insatiable gods of currency, but there’s also a superior grade of time spent outside riding bicycles aimlessly without a route or a goal or any idea what’s going on.

Petor now helps run Bespoked, the handmade bicycle show. Check out our coverage of the event here.

Story tags