For this month’s Back From The Dead I’m going to go into something that really raises my hackles: when the faceless corporate big-box auto-spares multi-sport camping-stores bring out bikes to play catch-up with whatever is the bicycle-du-jour of the moment.

I’m not saying that these big box stores don’t make some absolutely awesome bikes for great value but… a good few of them also make some right lemons.

Case in point: entry-level e-bikes.

There’s definitely a big market for low cost e-bikes, and justifiably so. They’re a great way of commuting and they’re definitely playing a huge role in introducing whole new demographic of people to cycling who otherwise wouldn’t have ever have been interested in traditional analogue(?) cycling.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

Can you really keep the costs down to just a couple of hundred quid more than the non-electric version and still sell a good quality product?

In almost every case I’ve seen the answer is a resounding… no.

The sheer cost of fitting a motor and battery means that some kind of savings are going to have to be made elsewhere.

The first places that suffer are generally the bars and seatpost. What would normally be anodised aluminium units are often swapped for cheaper, heavier steel versions. Steel seatposts with removable clamps à la low-end kids bikes are de-riguer for these bikes.

You don’t necessarily notice the extra weight (due to the extra overall weight of the bike) but the dead ride feel of a set of hi-tensile steel bars is instantly evident on the trails if you’ve ever tried anything better.

I’ve also seen several lower-end e-bikes where the battery is mounted directly to the bottle cage mounts! Riveted threads that sometimes struggle to stay mounted in the frame with just the weight of a 500ml bottle, in this case supporting the entire weight of an e-bike battery. Sounds like a recipe for disaster to me. Not to mention, where are you supposed to mount your bottle cage?

While I’m on the subject of batteries (potentially making this entire article another eco rant)…

What’s happening to all batteries from the low-end e-bikes that i see wheeled into the shop far beyond any kind of economical repair? Bikes that have only been owned for a year or two with huge lithium-filled batteries and motors stuffed with plastic encased in aluminium.

Bikes where the batteries or motors are covered in that horrible corrosion that looks like if you touched it with bare skin it would burn you.

As Ian the mechanic up at St Augustines (our local refugee centre) would say with a tear in his eye, like a modern day version of the crying native American staring out over a field of trash “another one thrown on the furnace!”

If manufacturers are making products that are such a burden on the earth to create, surely they have a responsibility to make sure that said products have a long service life and that service is actually possible?

Shouldn’t that be like, an international law or something?! Ok, eco rant over. Back to the original rant.

Drivetrains also go down a few tiers on these ‘bargain’ bikes. Generally all the way back to a screw-on freewheel instead of a cassette and a very bottom-feeder rear mech that is physically impossible to set up correctly. You want first gear? Best undo that low limit screw so far that the mech will be in the spokes with the slightest side side-breeze.

Remember: if the motor is built into the hub and you want to convert it from a freewheel to a cassette you’re going to need an entire new hub/motor! Not particularly cheap or economical to do.

It’s also worth noting that screw-on freewheels wear out pretty quickly compared to a modern freehub. Combined with the added torque of an electric motor running through them, they’re even more prone to self-destruction, as are all the rest of the bargain basement drivetrain components.

Oh yeah, chances are that the crank doesn’t have a replaceable chainring, so that’s gonna be a whole new chainset when it inevitably wears out.

Looking on the bright side, screw-on freewheels are cheap (about £15-20) and easy to replace though (if you have the correct tool) so there’s upsides and downsides for speccing them on budget e-bikes.

I have also seen a number of 8 and 9 speed screw-on options available from eBay (and other internet monoliths with CEOs who fly around in a giant space penises).

I’ve no experience of their quality. They tend to come from brands you’ve never seen before. Names like Shinmang, with a logo written in a font that if you squinted at it from a distance you could, possibly confuse it for a much more reputable drivetrain manufacturer. Maybe not ideal, but if you’ve already got a freewheel equipped e-bike it might be a better option than buying a whole new rear wheel to be able fit a wider gear range.

The brakes these bikes come fitted with are 90% of the time bargain basement cable discs. Woefully underpowered for stopping even an analogue bike, never mind an electric motored behemoth with – let’s face it – a fairly inexperienced rider aboard.

I don’t know if you’ve ever tried adjusting a cable disc brake but, if not, I’ll try to explain how they work as simply as possible and why they are a horrible choice for lower end e-bikes.

A traditional cable disc brake generally only has one pad move, this flexes the disc rotor over slightly and pushes it into a fixed pad on the side of the caliper.

To accommodate for pad wear you have to manually adjust the pad position. There’s an easy to reach cable tension adjuster for the moving pad but for the fixed pad it’s generally a 5mm Allen key bolt directly into the side of the caliper.

Easy peasy to adjust on a normal bike with a normal sized hub, but trying to do it with a chainstay mounted caliper and an enormous hub motor is physically impossible without dropping the rear wheel out completely. An easy if infuriating task for a seasoned mechanic but for these bikes’ target audience, nine times out of ten it’s just not going to happen. So the vast majority of these types of bikes are riding around with virtually no rear brakes.

An easily adjustable cable front caliper on the left and an absolute nightmare sent from the seventh layer of hell to adjust on the right

Now I know these are pretty wild and unprecedented times in the cycling industry with parts being delayed for literally years in some cases. It’s not surprising to see bikes with slightly odd spec choices as product managers scramble to find parts that look like they’ll just about do the job.

But it seems to be with most of the lower end e-bikes that the people speccing these bikes are focusing more on the ‘looks like’ rather than the ‘do the job’ parts.

The last thing I want to make clear within all this is… I’m not a bike snob.

I’m not trying to get everyone to go out there and buy some super expensive, bells and whistles e-bike.

If a cheap e-bike is all you can afford by all means go and buy one. But do a bit of reading first about what’s good and what’s not.

Please do your best to take care of it so it doesn’t end up scrapped in a few years. Pay a visit to your local bike shop. Ask their opinion about whatever big box store e-bike you have your eye on and whether they’ll fix it for you if it does go wrong.

Personally I love the challenge of working on odd stuff (not that I won’t be swearing about it while I’m doing so!). I do know that some bike shops don’t even touch e-bikes that they haven’t sold themselves.

Anyway, on to today’s case study.

This hardtail e-bike came specced from the factory with a single front ring without any real form of chain retention.

The customer brought it in with the chain derailing whenever he put any pressure on the pedals riding out of the saddle.

The original chainset has a cheap pressed steel chainring with shallow teeth and no retention system built into the ring.

We replaced the stock chainset with a second hand crank arm from our spares with removable rings and fitted a 42T narrow-wide chainring. It may not be the prettiest, but it’s functional!

The customer still wasn’t entirely happy that there was no cage around the chain to prevent further derailments but times are tight all around and he couldn’t spring for a new chain device right now.

I hate to send someone’s bike out when they’re not totally happy with it though, so I put my bodging hat on and got to work…

I decided to fit an old front derailleur as something of a rudimentary chain device for an added level of protection.

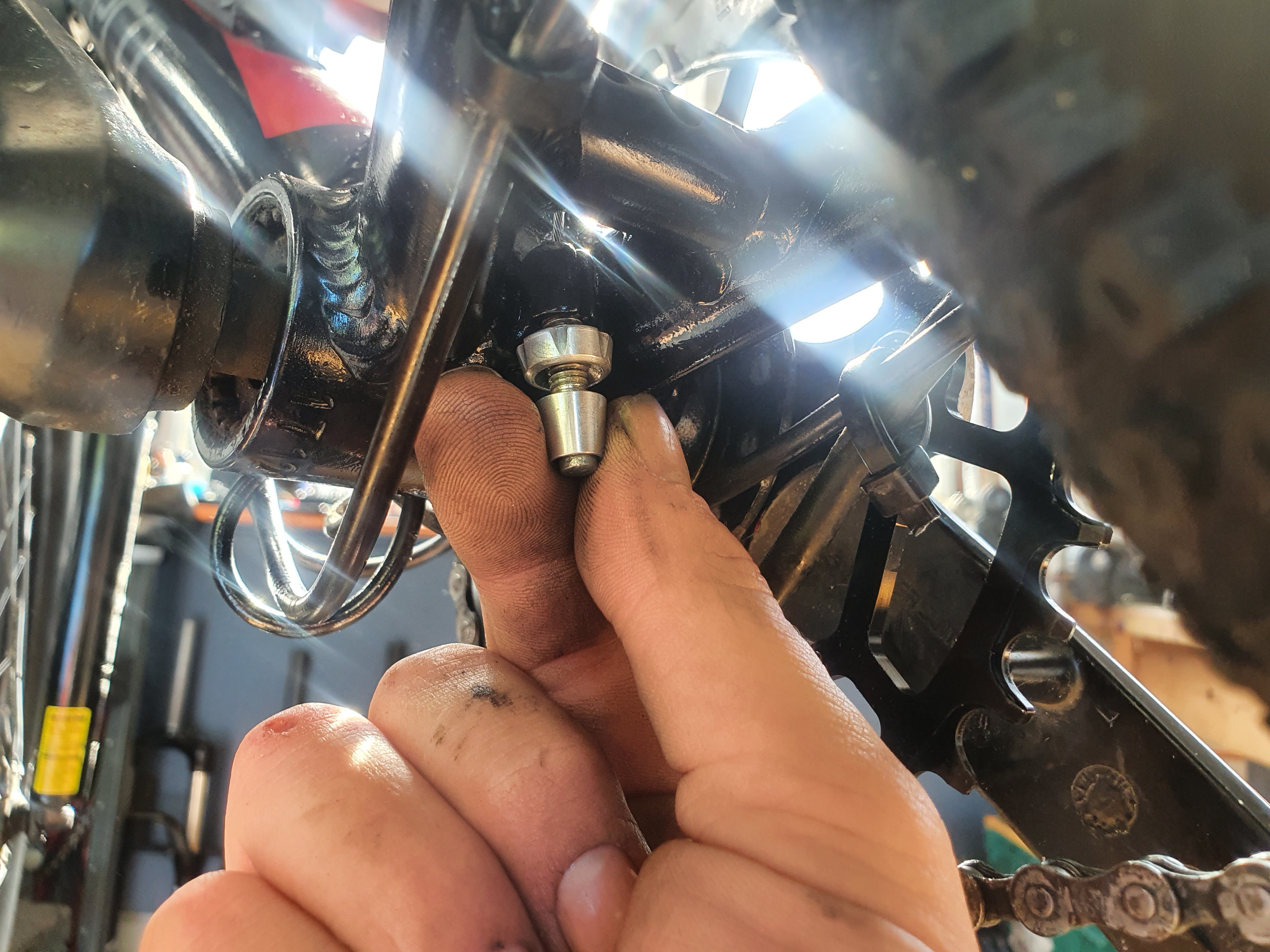

Getting the derailleur to sit centrally over the chainset was a bit of an issue. Without enough adjustment on the limit screws to sit the mech in a central position over the ring, it became quite the head-scratcher.

Thankfully, as this frame isn’t an e-bike specific one, it still has mountings for a front derailleur cable to sit under the bb shell. Meaning that once again, with a quick dive into my spares box and my scrap recycling bin, I can find…

Fits in an absolute treat. The lockring of the barrel adjuster is held in place nicely against the bottom bracket shell to make adjustment a pleasingly one-handed operation.

Now it’s just a matter of pulling the front derailleur into an almost central position and clamping the cable down.

Looks very neat (if I do say so myself).

Wind the barrel adjuster out until the derailleur cage is properly aligned over the chainring.

The final task is to make sure that the derailleur cage doesn’t rub at the extremes of the gears. As this front derailleur won’t be used for its original intended purpose, again a little bit of ‘precision bending’ took place to make sure it was well clear of the chain at all times.

The bike is then given a vigorous test ride on some local cobbles to make sure that the problem isn’t going to resurface.

It rides a dream!

Join our mailing list to receive Singletrack editorial wisdom directly in your inbox.

Each newsletter is headed up by an exclusive editorial from our team and includes stories and news you don’t want to miss.