A few rolls of lost camera film bring back memories of older times.

Words & Photography Chipps

The fading art of the analogue photograph was always a wonder to me. I can remember watching, amazed, as my first black and white print appeared before my eyes in the college darkroom. Then, a few years later, I would regularly get ‘photographer’s angst’ as I waited for my exposed films to come back from the developers to see how many of my 36 shots yielded useable results, if any. The slide film we used in pre-digital magazine work was particularly hard to work with, meaning that every shot was taken with care. None of the ‘spray and pray’ photography possible with modern digital cameras.

So, when a recent house move turned up a half-dozen film canisters, each with an exposed film inside, I was moved to send them off to be developed, just to see if those carefully curated shots were still etched onto those strips of light-sensitive film. I wasn’t hopeful, because I couldn’t remember when they were from, and film doesn’t really like being left in the can for what could have been, must have been, over a decade. I hadn’t shot film since digital cameras got ‘good’ in the mid-2000s, so who knew when these films were from?

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

The big reveal

Some 60 quid and a couple of weeks later, I got my slides back. I’d not paid extra to get them mounted, as I didn’t have high hopes for them, but I had got them scanned onto disc. A couple of rolls were in good shape; they were from the Singlespeed World Champs in Stockholm in 2006 – vivid colours, familiar faces and, within the constraints of a 35mm rangefinder camera, pretty sharp.

Three other rolls, though, were just a riot of crazy colours. Some shots were completely turquoise, like an explosion in the Yeti paint shop. There were a few edges to discern, but not much else to go on. I figured that these rolls of film must have been shot 20 years ago to have degraded so much. Nevertheless, I imported them into my computer and had a play with the colours and the levels to see if I could get anything out of them – even if it was a date or a place to show where I’d forgotten them from.

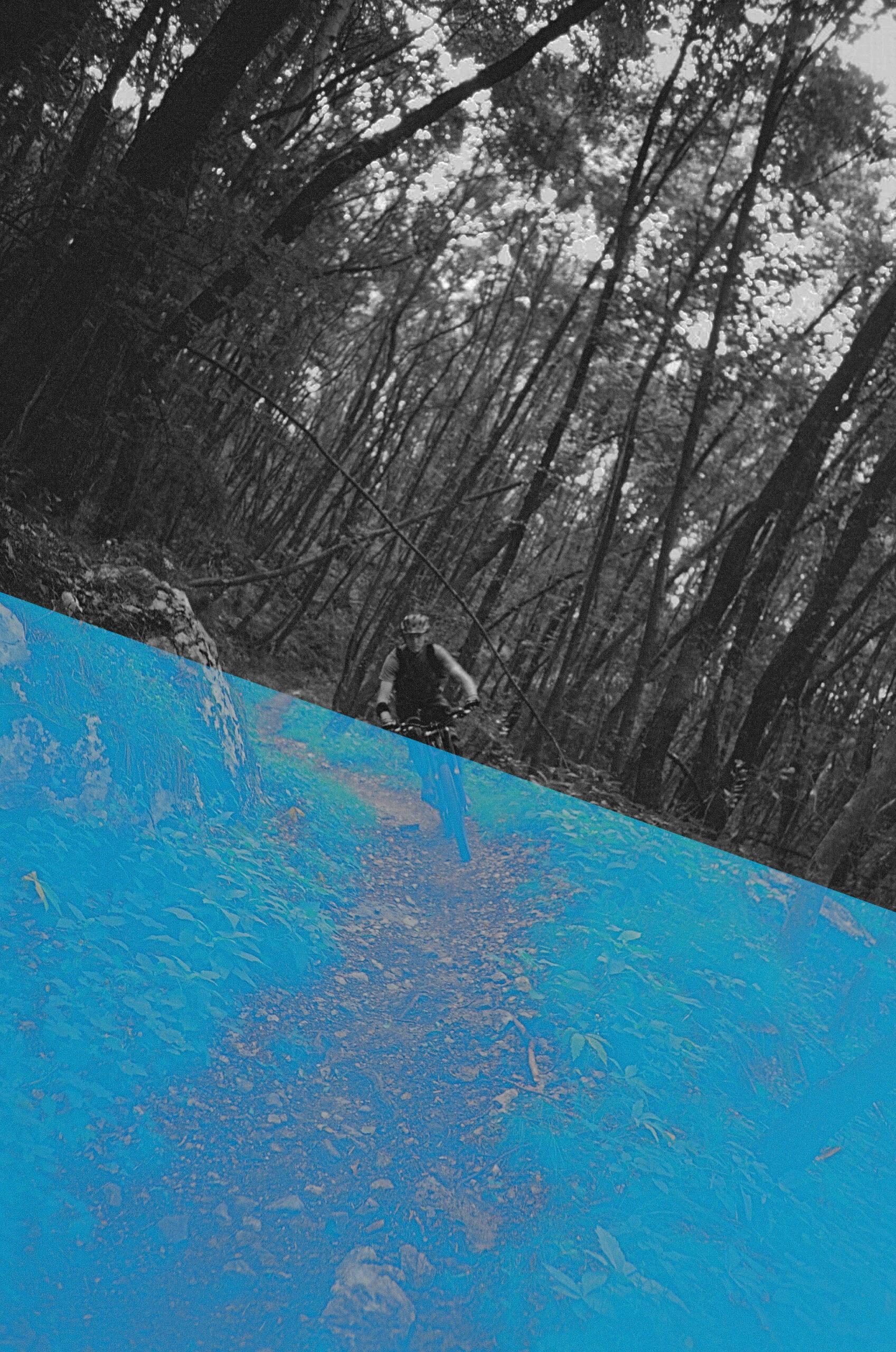

Less cyan, more magenta, or was it more yellow? I’m not a natural when it comes to colour balancing photos. It seemed that I could only make things worse. The splotchy, faded slides would forever remain a mystery. Until, that is, I took all of the colour out of the images on a whim. Suddenly, freed from the bleeding colours of the old film, the photos jumped to life. There were bikes, and people and mountains! Now to work out where and when they were speaking to me from.

The fact that anything was salvageable was a testament to the marvels of photographic chemistry. Photography in the pre-digital age was a bit of a lottery. Film wasn’t as sensitive to light as a digital sensor is now, so for action sports you were working with a very narrow window of usability in order to freeze the action, before you had to punch in a flash gun, or pan the camera to catch the rider. If it was still too (relatively) dark, you’d have to ‘push’ the film to make the camera think that it was more sensitive than it was – which then needed an equally understanding photo laboratory to ‘overcook’ things when processing to coax a decent result out of your stressed film.

Grainy memories of sharp climbs

Once I had that key, the trick that basically transformed a turn of the century photo into a photo from the turn of the previous century, photo after photo started giving up its secrets and my memories of a mountain bike trip, now 20 years past, began to coalesce into a coherent story.

It was the summer of 2001, possibly 2002, and Singletrack was in its early days. We had no budget, but did have big ideas and an ability to improvise. Midsummer launches in the days leading up to the Eurobike show provided an excuse to get to Europe early. My US journalist friend Mike Ferrentino provided yet another favour by picking me up from a random cut-price airport on the way to the same eventual destination.

For some reason, both of us had been early adopters/enthusiasts of Maverick bikes. Mike had just been Interrailing around Europe with his for a feature in Bike Magazine and I had managed to bring mine on my Ryanair flight, before they started charging a fortune for them.

Maverick had rented what turned out to be an ancient farmhouse, near (but not expensively near) Lake Garda, and a bunch of New Zealand friends had joined up for the ride. Luckily, there was enough room for a couple of floor-dwelling journos like Mike and myself and, as we had the right bikes with us, we were allowed to tag along.

DUC forking

The excuse/reason for the Maverick jamboree was some pre-launch testing of Maverick’s dual crown DUC fork. Impressively ahead of its time, the DUC was a lightweight, air-sprung, 150mm travel fork for cross-country riding. These days, that sounds laughably commonplace, but back then, six-inch forks only appeared on downhill bikes and even then, only with coil springs. Maverick’s boss Paul Turner had founded RockShox back in the late ’80s and was determined to upset things with this new brand of his – hence the name.

Of course, ’90s geometry was still influencing bikes, so although our 150mm forked bikes had pretty progressive, for the times, 69°–71° angles, they were still short and steep and sketchy, made even more so once that easy fork travel started to dip in and the rear suspension started to sit up a bit.

Our couple of days of product testing coincided with the oppressive heat that mid-Europe gets at the end of the summer season. Days were blisteringly hot and rides either had to be done and dusted by noon, or to take in several gelato parlours to make things bearable.

We started with a day of bike fettling and running in of these new forks, a bit of exploring and some seeing of the impressive sights around Lake Garda’s near-vertical cliffs that plunge down into the huge lake. Over dinner, plans were made for an epic ride suitable for a bike deemed ‘the best climbing suspension bike, ever’ to match the apparent downhill prowess of these new forks.

The itinerary for our final day was to climb – for THREE HOURS – from near sea level up to getting on for 2,000m in order to take advantage of the resulting hour-long descent back to the Garda lakeshore. Conditions were baked dry and there was no sign of the midsummer thunderstorms that can appear unannounced in the mountains. (The thunder and lightning would appear a couple of days later and completely upset a Specialized launch a couple of hours away in Germany.)

Due to the heat, we’d have to be on our way early – and despite my dislike of early mornings, we were rolling before 8am. The day was hot already, with a blue sky and a searing sun. Our climb did indeed take three hours – on road, then unshaded fire road. But our descent was a solid hour or more of testing, technical singletrack all the way back to the lakeside road. It was a great test of the bikes and it was a fantastic ride.

The old photos from that couple of days gave me glimpses into some of those moments. As I looked through them, every so often I’d almost feel that oppressive heat and the scant breezes from the lake that provided a moment’s respite.

Capsule collection

At the time, this trip was a new adventure on new bikes with brand-new, cutting-edge technology. Now those turn of the century Maverick bikes aren’t yet old enough to rouse nostalgic fervour in middle-aged collectors, but they can’t hold up to modern trail bike scrutiny.

However, having those old slides preserved as literal time capsules for a long-forgotten European trip has brought back to me the power of photos and the difficulty and fragility of pre-digital photography.

Photography today is a commonplace thing. Anyone who has a phone now, has a camera. A photo costs nothing to shoot and they nearly always come out well. Apparently now, there are around 55,000 photos taken every second and more photos taken every couple of minutes than were taken in the entire 19th century.

The mystery of a roll of film and the subsequent magic in the developing room is lost on anyone born in the 21st century. The expense of film and the limit of 36 exposures made you choose your moment, whereas now every single moment of our lives can be recorded on the phones we all carry. And yet, there is something still special about a physical photo or slide. That slide, or negative film, was physically there to witness that actual moment in time.

And, although faded and grainy, these 35mm pieces of film hold an amazing power that takes me back to that trail, that morning, that conversation, that ride…