How much physical and mental strength does it take to finish, let alone win, the 1,800km Great British Divide? More than we could ever imagine.

Words & Photography Chipps & Chris Hinds

How does that kitsch saying go? To truly appreciate the heights, one must first start at the very bottom. Something like that. Or else I’d suggest ‘The higher up you start, the longer it’ll take until you hit rock bottom’.

And that, I think, is the secret to Chris Hinds’ surprising win of the epic, yet virtually unheard of endurance ride – the Great British Divide. I reckon that he is such a naturally cheerful and upbeat guy that he had a longer descent into misery and madness than some of his rivals, which meant that it simply took him longer to get there. He was also fast enough to avoid the constant rain that dogged many of his rivals for a little longer, until he too had to deal with soggy kit and the (very real) threat of trench foot.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

It goes where?

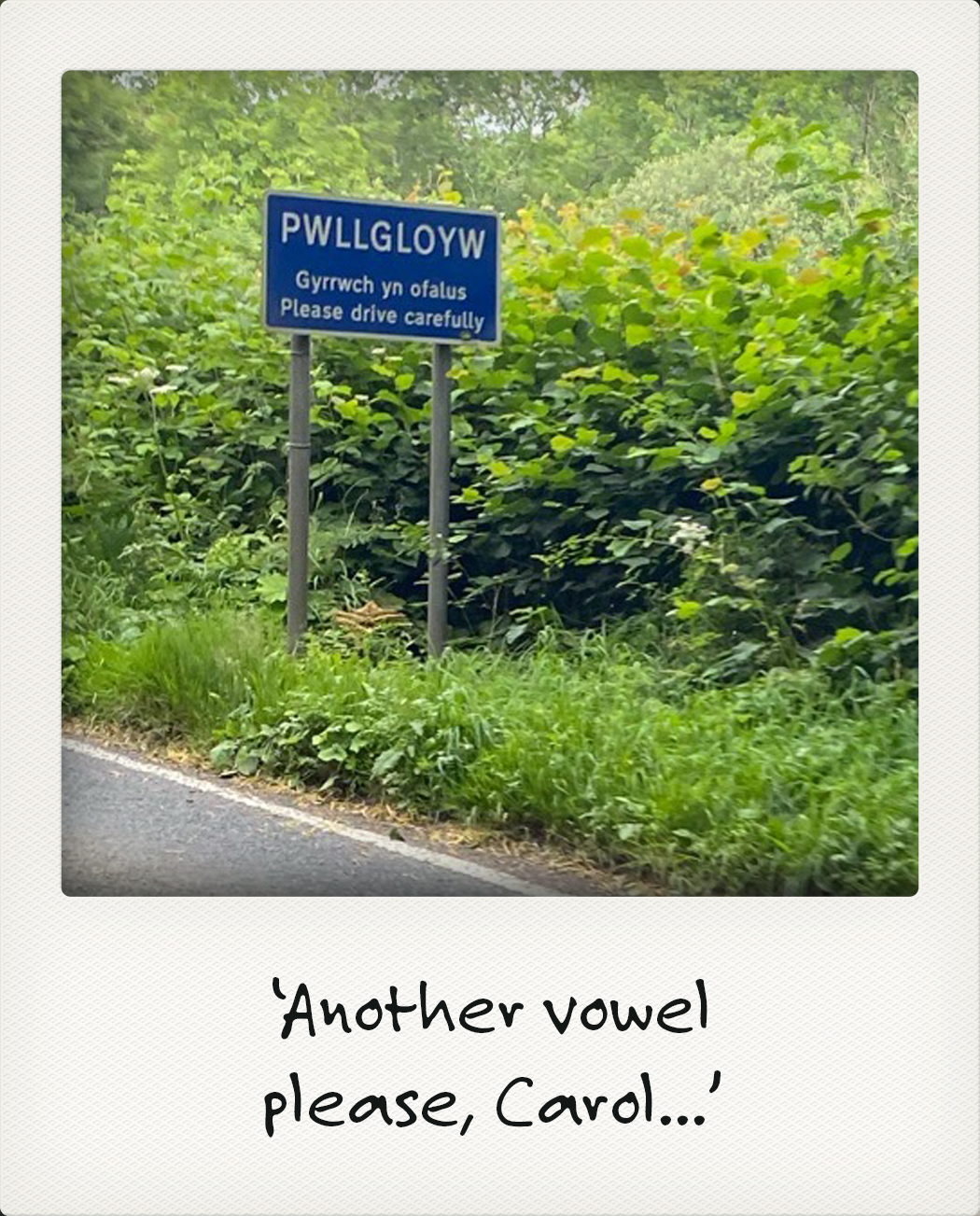

I’d barely heard of the event until it started. The Great British Divide is a mostly off-road, 2,200km, self-supported bikepacking event that started late July 2021 at Canterbury in south-east England and took a long, lazy arc west, through the South Downs, up to South Wales and through the Cambrian Mountains before taking on the spine of England. With the Peak District, South Pennines, Yorkshire Dales, North Pennines, and Kielder Forest to ride, you’re finally in Scotland. The route then takes you through Peebles (the hard way), over Edinburgh’s Pentlands and then over to Glasgow, ready for the 100 miles of the West Highland Way up to Fort William. The plan then was to finish with a lap of Skye and a final grovel over the Bealach na Bà to finish in Applecross.

In the end, the treacherously wet August weather caused the race to be shortened to finish at a mere 1,890km or so from the start.

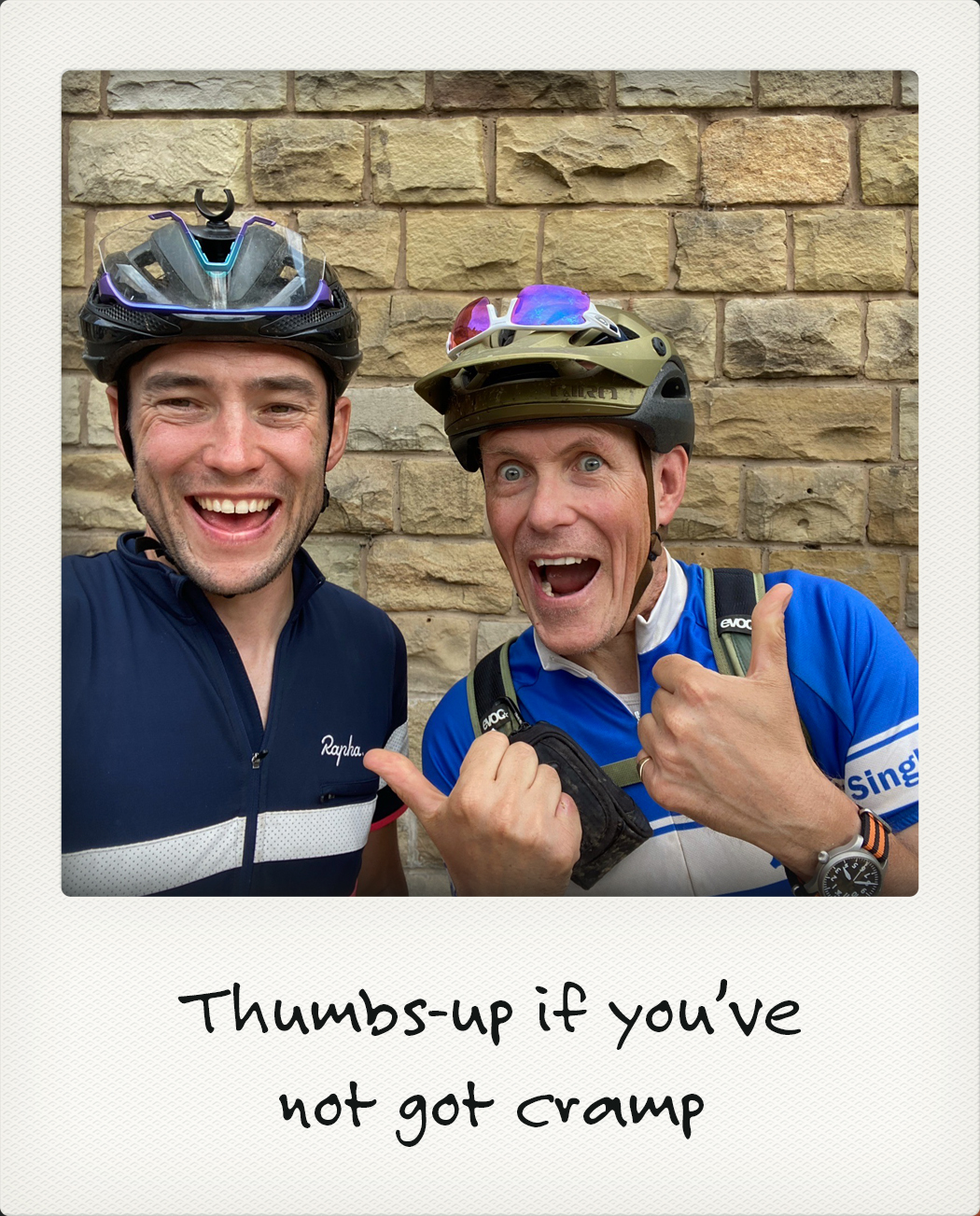

It turned out that the route went within a couple of miles of Singletrack’s office, so I rode out against the course in an attempt to intercept the leader, Chris. By the time I caught up with him, he’d already ridden 1,100km and was, ostensibly, halfway through.

As we rode together for the next hour, he chatted with the levity of someone out on a Sunday club ride and the speed and ease of a seasoned racer on a day off, rather than a chancer who’d never won an event in his life, who felt he was about to be unmasked and reeled in at any moment.

Cobblers!

Before lining up last August, Chris Hinds was a true outsider in the tight-knit and small world of ultra-distance mountain biking. While he’d done the road-based Trans Pyrenees event in 2020, he wasn’t known as a long-distance mountain biker, and he admits that his race entry was based on a mid-summer search for races that had any space left, leaving him with about eight weeks to train and get a bike and kit together.

While other riders had factory support, or custom bikes built just for this event, he didn’t have a pre-2008 bike to his name and his eventual race bike was cobbled from an old Gary Fisher hardtail, some drop bars stolen from his commuting bike, borrowed tri bars (for hand resting, rather than aero reasons) and a 32T chainring purely because that’s what he could poach off his singlespeed. His luggage and clothing was also borrowed, patched or threadbare. The only new bits of kit he had were a hub dynamo and a pair of two-race-old cycling shoes. Even the dynamo he reckoned was a bit much as it needs an average speed of 12km/h to charge anything and his average speed on the brutal course was slower. Much slower.

Even his training hadn’t seemed to have put him in a good place to finish, let alone win among the field of 46 or so racers. His longest ride in 2021 was 120km and no other rides topped three hours ‘due to boredom’. Luckily he spent a whole two weeks getting his bike ready before the start to keep his mind from the enormity of the task.

Descent into madness

Reading his diary entries, he starts off cheerful, happy to be there and perhaps a little surprised to be in the front group with favourites like Josh Ibbett and Donnacha Cassidy, but anyone can ride fast for ten miles, perhaps even a hundred. It’s the slow decline after that in which this event is won or lost.

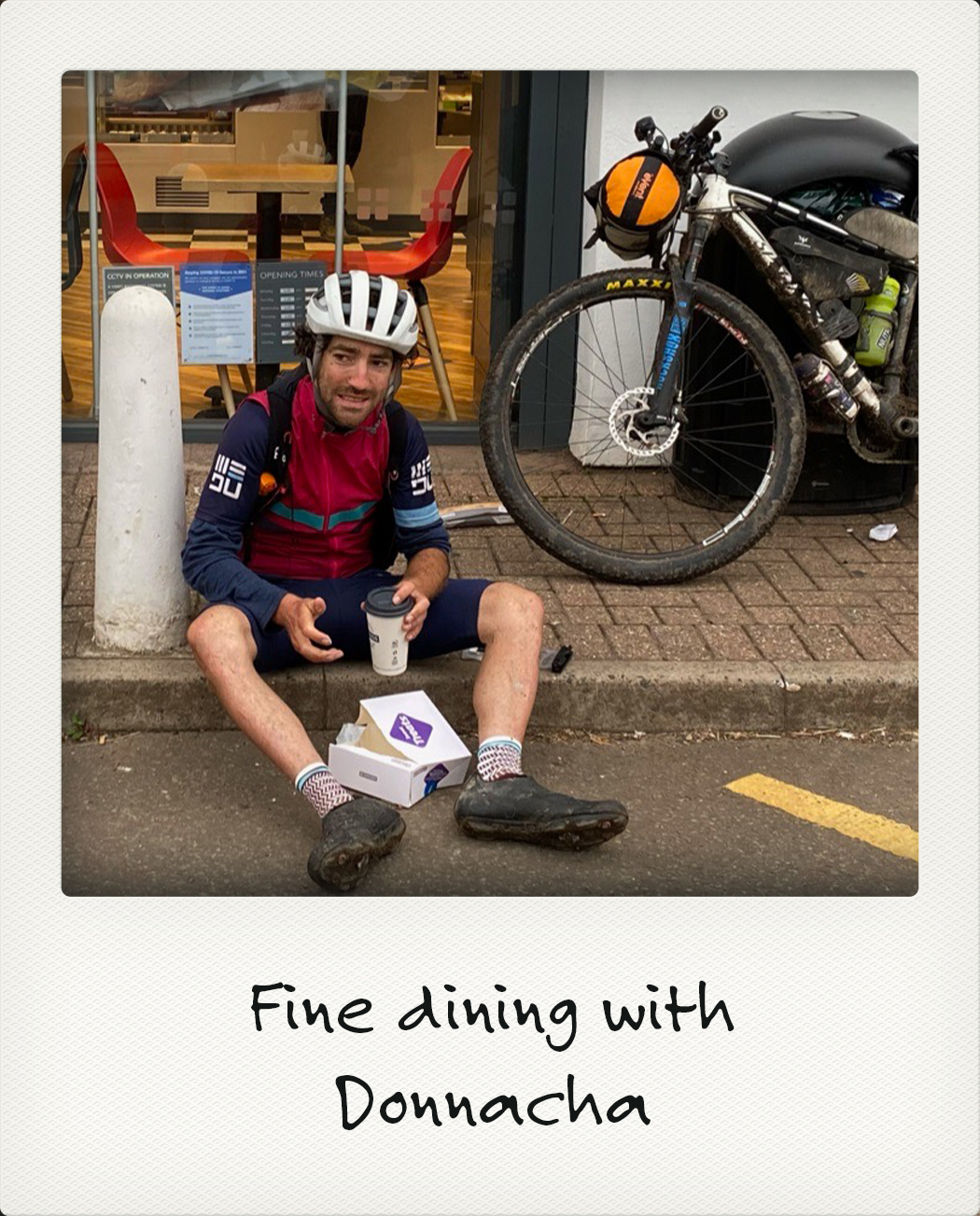

When I catch up with Chris again a couple of months later he admits that he didn’t really know what he was doing. He’d never ridden in many of the parts of the UK he was passing through – which was part of the appeal of the event. That lack of competitive drive/practice/organisation showed every time he stopped, as he’d chat and faff, and spend time choosing food, where his peers, like Donnacha would blitz into a shop, buy the highest calorie foods available in the shortest time and be gone before you knew it.

It seems to be one of those sports where the longer you do it, the better you become at it. You become efficient packing your bags, you know where to sleep to get the most shelter and the quietest night and you probably know just how much of the time you’ll be pushing or throwing your bike.

It’s a long game in the true sense. Riders in a 2,000km event don’t particularly break or blow up, they just seem to wear out – and it’s in managing that decline that the winners emerge. In the same way as climbers above 8,000m know that what they’re doing is ultimately unsustainable, so the endurance racer knows that he or she is on a steady decline to zero and they desperately need to slow that descent long enough to get to the finish.

There’s a fair amount of luck involved too. When Chris was riding past Todmorden, he claimed that the reason he was pressing on so hard was so that he could enjoy the remainder of the time he’d booked off, doing nothing. The faster he finished, the more he could relax. Whether he believed that himself, I’m not sure. As it happened, the band of heavy rain that sat over the second week of the event would have far more effect on riders’ morale than the terrain, and Chris’s early speed kept him ahead of it for a while. With August temperatures dropping to low single figures overnight, any rider who hadn’t packed pessimistically was in trouble.

But why?

Endurance racing is still a new sport. There’s no governing body and no real pecking order of legends of the sport established just yet. This leaves the sport open to (fit) chancers like Chris to have a go.

But why would they want to? From the outside, it appears to lack any saving graces at all. Riding your bike when exhausted, losing the feeling in fingers, feet and genitals, all while eroding your bike, clothing and credit card to destruction can’t be good for you, surely?

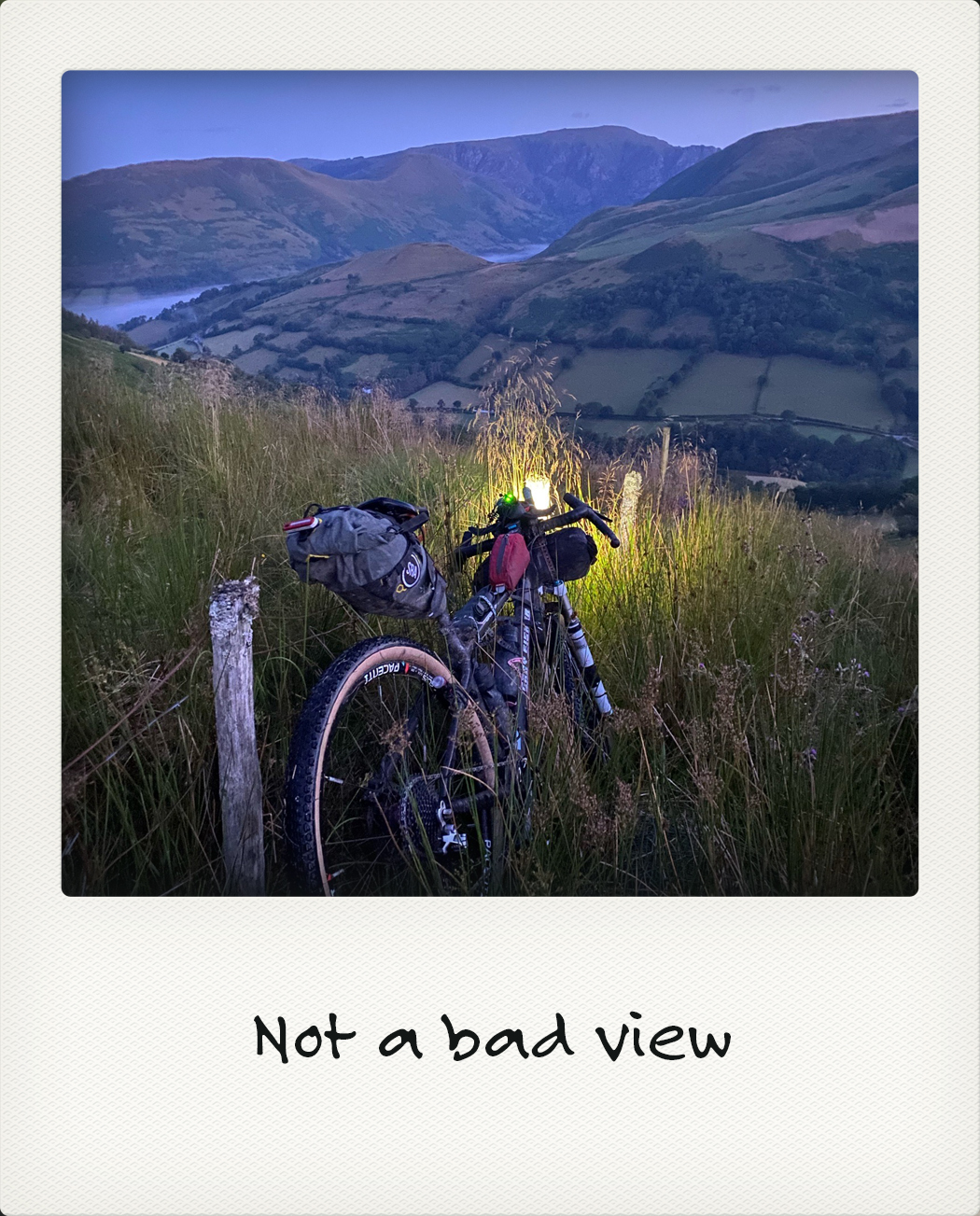

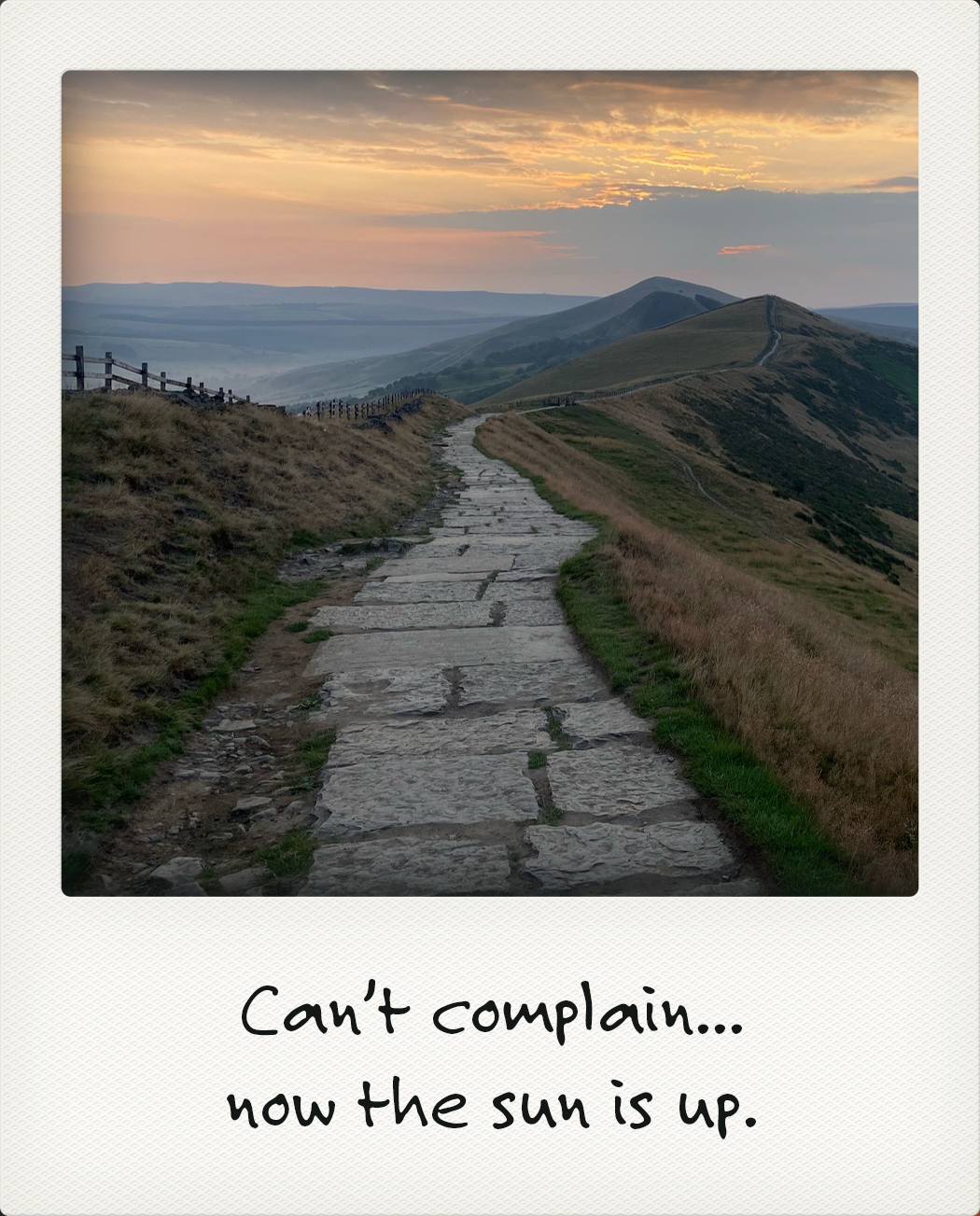

Chris argues that there were many high points to contend with the lows. Seeing an early dawn inversion from the top of Mam Tor, riding through so much of England and Wales he’d never have seen otherwise… And then there were the people. Friends and colleagues he’d not seen for years came out to cheer him on. Random strangers offered spare rooms, or to charge his lights and fix his bike.

As he puts it, he’ll never do any sport well enough to get to the Olympics, but long-distance bikepacking offered him the chance to ride at the head of a prestigious event and to fight for the lead, knowing that hundreds of friends and strangers alike were watching his GPS dot on the map and willing him to finish.

As it was, the course was shortened (slightly) due to the weather and Chris went from the verge of packing it in to the eventual win, though even that was fraught with issues after the eternal search for USB power let him down on the edge of Fort William.

You can read some of his diary entries here, and we’ll be publishing the full epic in the digital magazine so that you can join his descent from cheery chappy to dark and tortured soul as he rode north.

As Chris says, though: “Don’t forget the adventure aspect. This is your adventure. If you knew you were going to finish, it wouldn’t be an adventure. There are no prizes and it’s just for fun, so don’t sweat the small stuff, don’t overthink it. I thought I was never good enough… but a bit of ‘f*ck it’ goes a long way.” And with that, he doesn’t expect that he’ll be on the start line to defend his title at the next one.

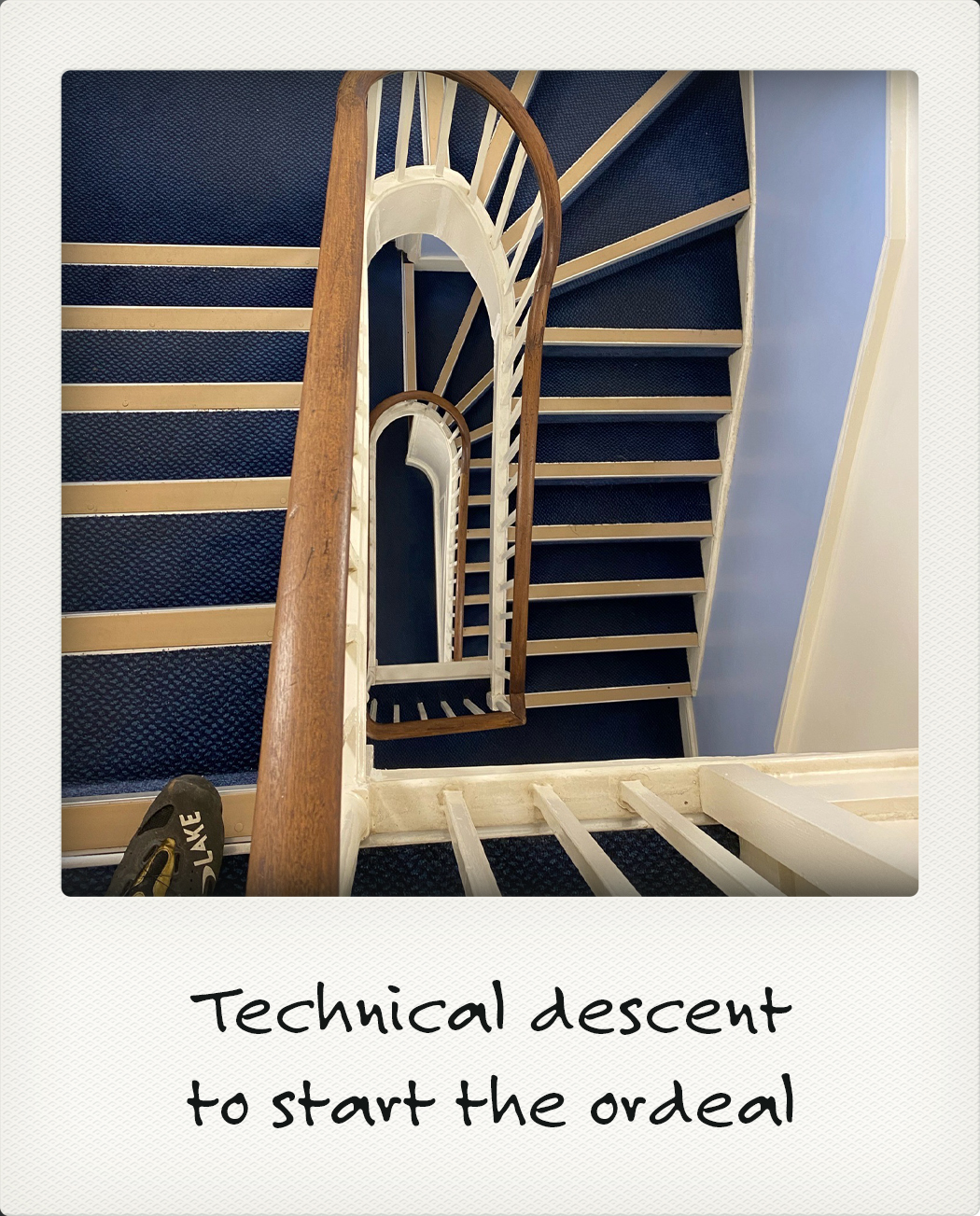

Day 1 – Canterbury

First section of hikeabike comes in the form of trying to negotiate my loaded bike down the spiral staircase of ye olde Travelodge, an omen of things to come… It’s a 10km ride to the start line but not before I’ve found a postbox to post my casual clothes home, a cunning plan to avoid carrying excess kit. That is, until I get the postal bag stuck and end up standing at the side of the road punching a postbox till it reluctantly accepts my offering.

Day 1 – South Downs

The change in topography upon hitting the South Downs is jarring, gone are the winding bridleways, replaced by steep chalky singletrack climbs onto the top of these rolling hills with amazing vistas over to the South Coast. The views to the sea and the slowly setting sun is amazing and, to an avid childhood fan of MBUK, pure, utter Mint Sauce. I’ve never seen anything like it. Smiling at the memory while churning across the draggy grass tops of the hills, it feels like I’m riding over giant pillows; steep climbs onto a big, rounded top before a screaming descent back down, wash, rinse and repeat for 100 miles.

Day 2 – Somewhere on the South Downs

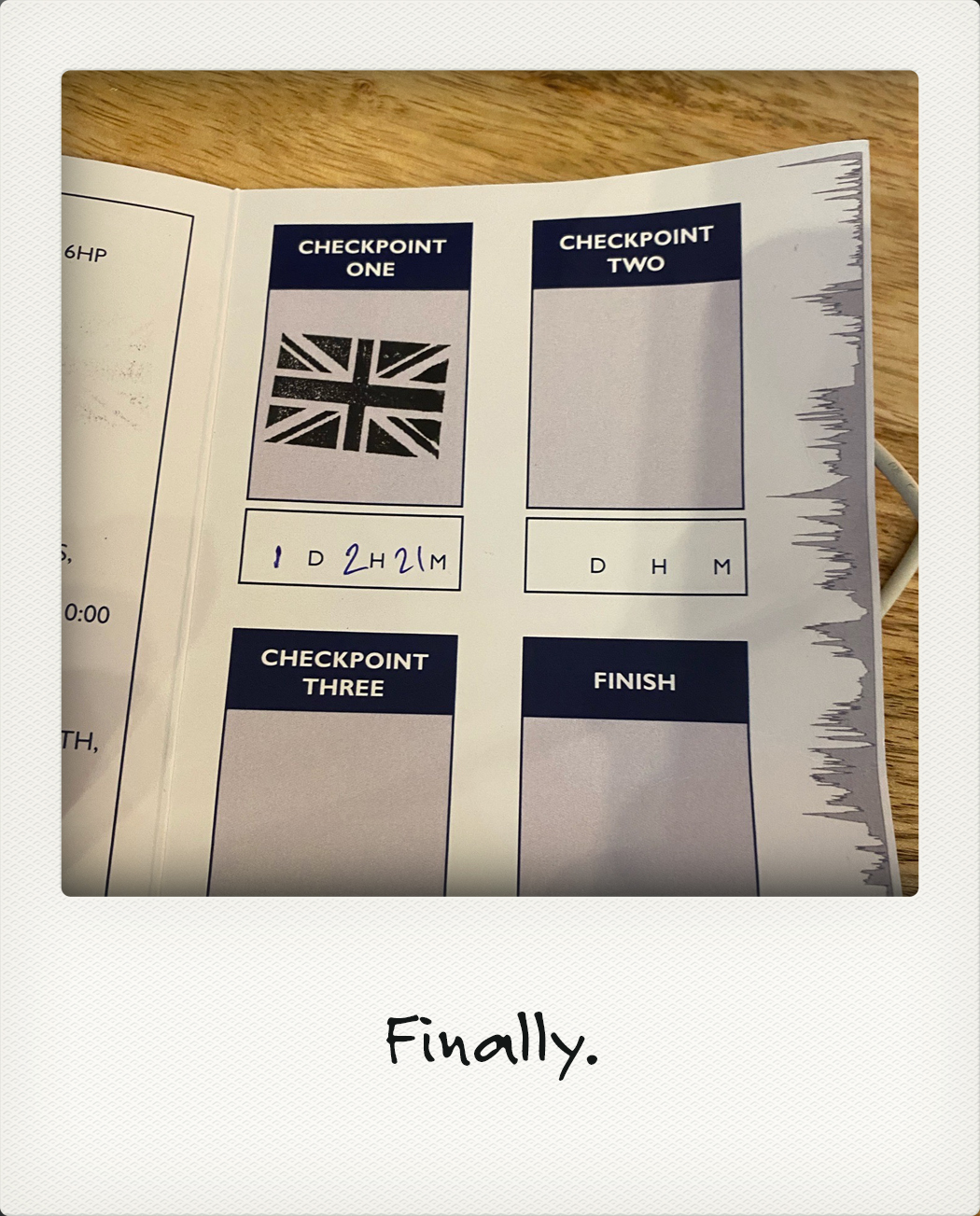

Big push onto Checkpoint 1 in Winchester, just a bit of a slog up the remaining hills of the South Downs Way but with the checkpoint in sight, morale is high as I trundle over the remaining 70km. I roll into Winchester on market day, weaving precariously around the shoppers as I try to find the checkpoint. Uncertainty sets in as I stop to check the race manual for Checkpoint 1. CP1 is Lyndhurst, not Winchester. Dick.

Day 3 – Offered a bed in Batheaston

For the most part, cycling is a sport for the privileged; we’ll never need to rely on handouts or really engage with the kindness of strangers, perhaps making it all too easy to only see the negative aspects of humanity writ large in the media. The daily discomfort of a wet ride balanced by the warm home we return to. Events like these strip that veneer of comfort away, a bed for the night and clean clothes quickly becomes an uncertain luxury, the exhausted dirty body sitting at the side of the road is an outlier to the daily goings on of society. The small (or sometimes large) gestures of kindness from strangers on the road are a refreshing tonic to the usual narrative of life.

Day 3 – South Wales

I roll up to find [eventual second place] Donnacha sitting on the pavement outside Greggs, midway through the four-pack pastry breakfast. I grab a couple of pastries and the by now obligatory chocolate doughnut before joining him on the pavement. The conversations have now become pretty structured and much like our bodies, slower. How you doing, where did you sleep, how’d you find the previous day and any news about the other riders? This Greggs has the added bonus of the petrol station toilet, a luxury not to be sniffed at (in every sense of the word!). Donnacha’s away while I faff again with kit set-up, no surprises there.

Day 3 – Brecon

Turns out a foot-long sandwich will fit in a thigh cargo pocket without too much bother. Trying to then get it out and eat it though is another matter altogether, so I leave the good folk of Brecon in a hail of lettuce and onion for the North.

Day 4 – Cambrian Mountains

There is a hell and it’s in the Cambrian mountains. I’ve been dragging my bike through waist deep grass for over an hour and I’ve just about covered a mile. Despite what the map says the path gave up its claim to this land a long time ago. Now it’s just long grass, a forestry block and barbed wire fences. The epic view is a small consolation for the unbridled hell of this morning’s climb, something that’s just rounded off by the bum shuffle descent down the vertical mess left by the Forestry Commission’s latest handiwork.

Day 4 Hartington, Peak District

The pace of service at the YHA is rightly sedate, part of me feels the urgency of grabbing food and moving on – the Donnacha stratagem – while the other part of me is desperate to enjoy a beer and relax. I opt for the latter and grab a beer, burger and brownie alongside a pizza to go. The sideways looks I get are an inevitable result of inhaling a family’s worth of food while ramming a pizza into a collection of freezer bags and old Greggs wrappers. Too soon I’ve run out of excuses to stay. Repacking the bike is something out of a comedy sketch as I put one item down, pick up another then put that down to repeat the process with the first item. Nothing seems to be fitting anymore and in a pique of frustration I punch the pizza and clothing back into my saddlebag.

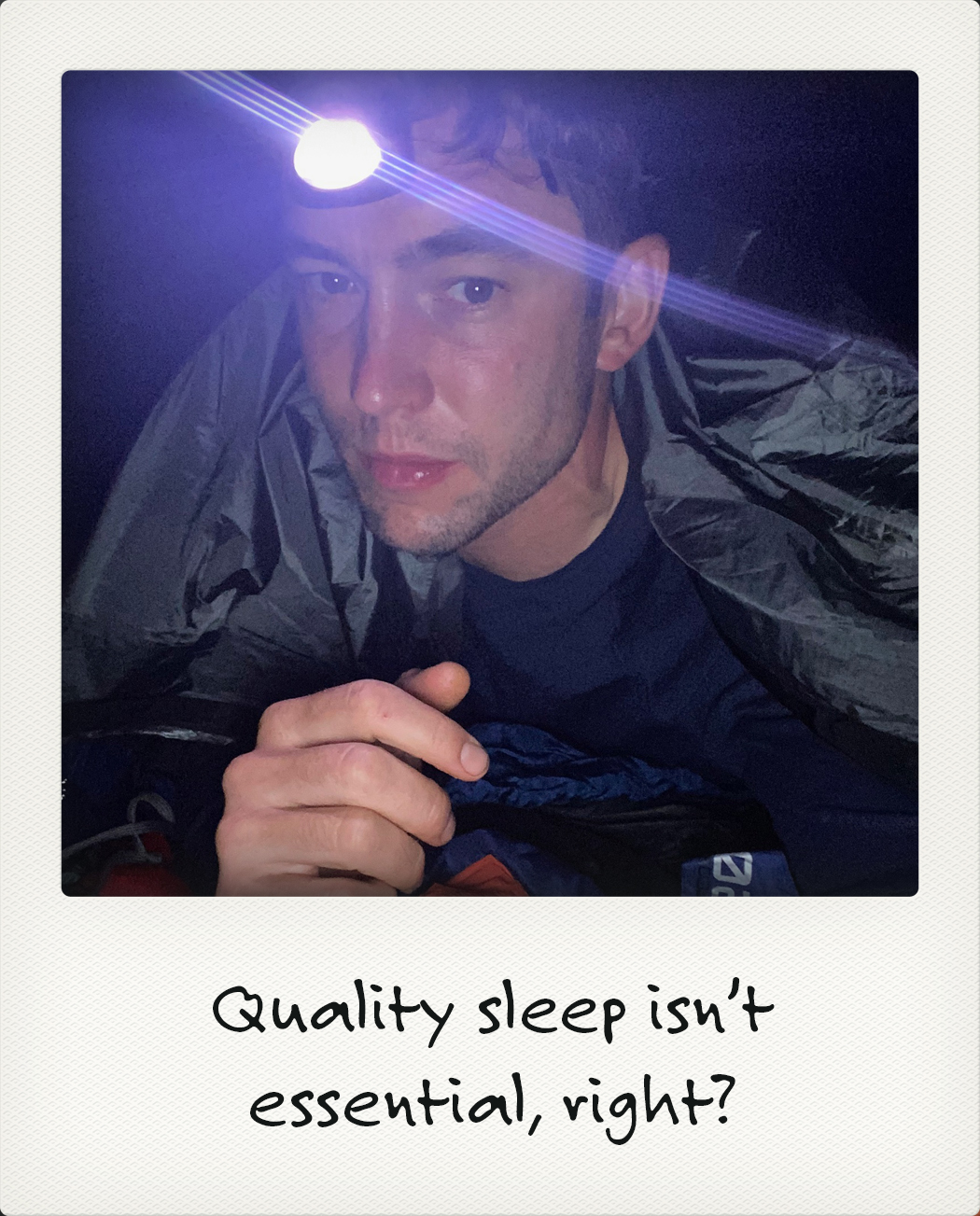

Day 5 – Mam Tor

I’ve clearly taken a wrong turn and ridden into the Arctic Circle last night. In the four hours of bivvy habitation (let’s not call it sleep) the temperature has dropped to 1C overnight. I’ve put off getting more layers during the night and the end result is uncontrollable shivering and a hint of desperation, as good a time as any to get moving. I can’t get dressed in the bivvy so fall out onto the wet grass in a state of undress, frantically pulling on all the layers I can, before wrapping myself in my sleeping bag (thanks for that tip, Innes!).

Day 5 – Hadfield, Peak District

Last night’s dried out, deconstructed, youth hostel pizza has managed to keep me going to the next resupply point at Hadfield. In four hours, I’ve made it 32km, I roll into the town utterly defeated, I haven’t checked the dots today but at the rate Josh was moving up, this will be my last day in the lead. I’m now well off the map in terms of distance and duration previously ridden and I can’t help feel that I’ve maybe paced this wrong. I slump beside the bin outside Tesco Metro with a wealth of comfort food.

Day 5 – Hadfield, Peak District

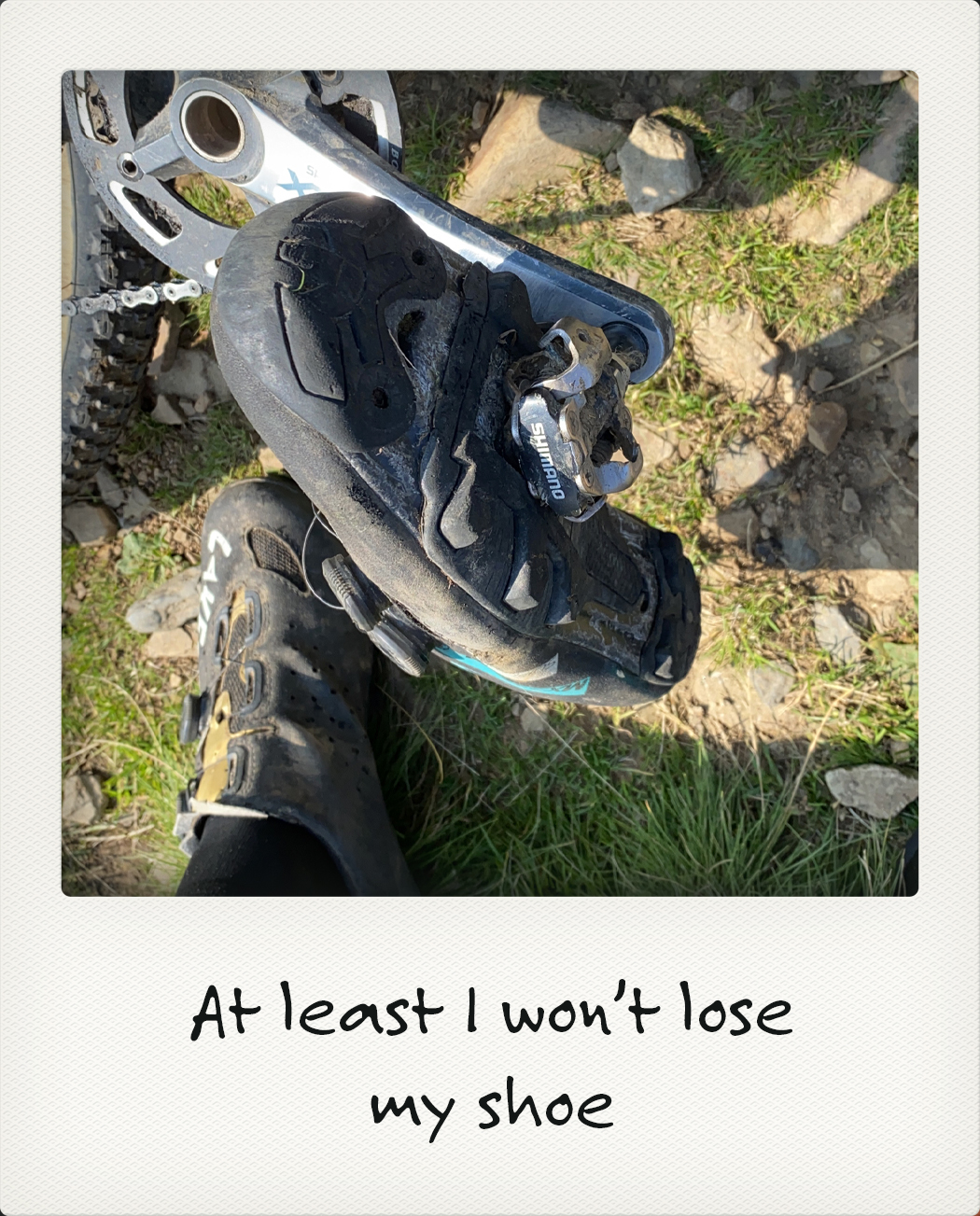

The renewed energy [from hearing that Josh had scratched] lasted as long as the start of the next climb, beginning to wonder if running shoes would have been a better option over SPDs. Shoe fears become reality when I find when I find out the hard way that you can’t unclip with one bolt in your cleat. The unscheduled lie down isn’t exactly unwelcome and I take a minute to consider the situation before pulling my foot out of my shoe and wrestling the cleat out with the help of an Allen key. I get my first chance to have a proper look at my shoes and groan, alongside a missing cleat bolt, the rubber tread is peeling and the carbon sole itself is starting to splinter. The bill for the event creeps ever upwards…

Day 5 – Todmorden, South Pennines

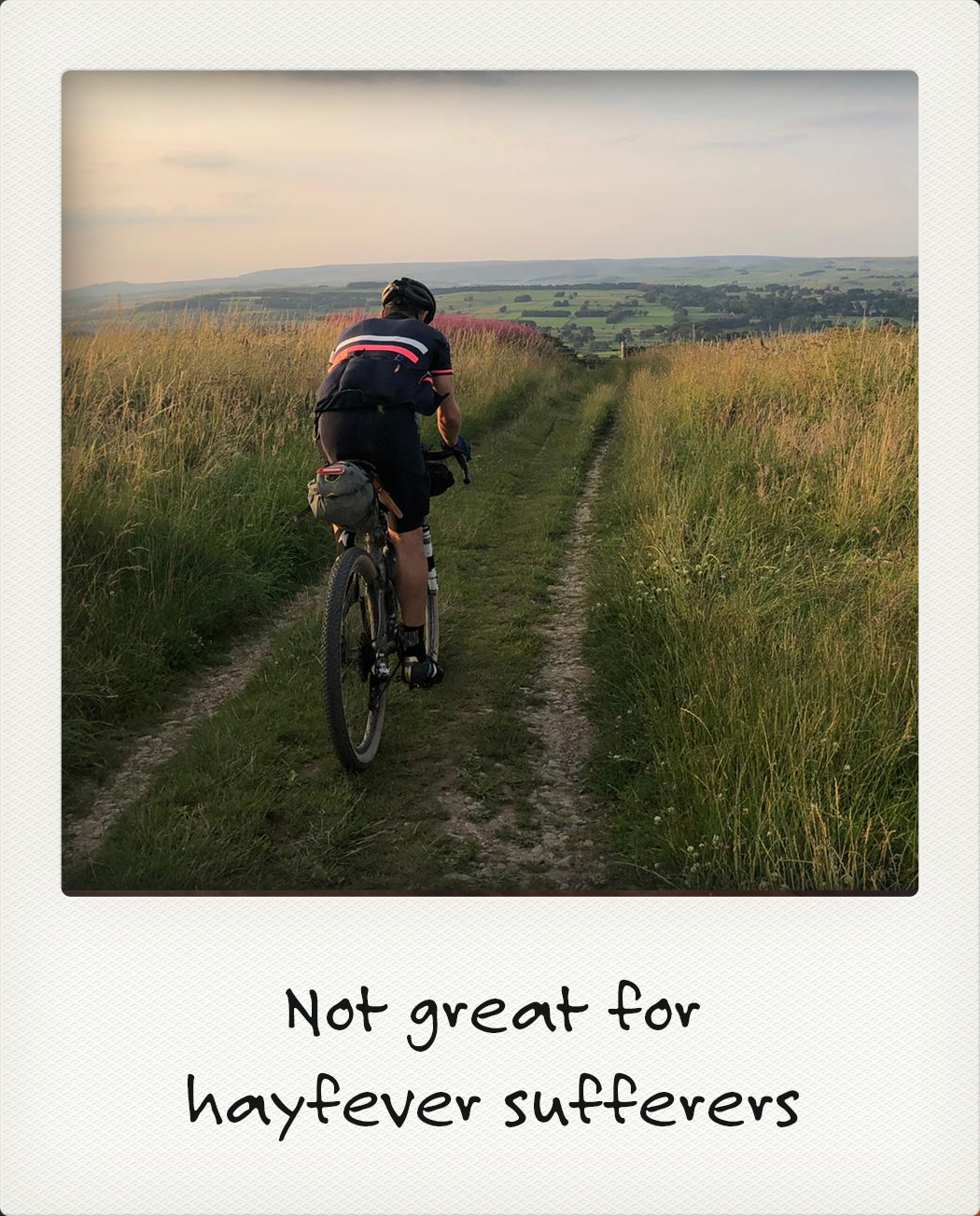

A farmer catches me just outside of Todmorden, saying my friend is just up the road waiting, I can’t think who I know around here but I put it down as another dot watcher and hopefully a bit of company! Round the corner there’s a figure up on the hill with a camera out. I quietly swear at them as I realise pride is going to mean not walking this part of the climb. As my calves scream in pain it occurs to me that falling over with cramp might actually be worse than walking. I don’t know the rider at the top but I definitely recognise the face, even if I can’t place it. It’s Chipps from Singletrack.

Day 5 – North of Hebden Bridge

I still haven’t actually figured out a stop for the night. Some frantic googling and there’s one room left in the only hotel within a rideable distance for the rapidly approaching night.

Day 5 – Posh hotel near Barnoldswick

The setting sun brings with it the first of the bad weather that the rest of the riders have already been hit with. In the space of an hour the temperature drops 15C and the rain turns the bridleway into a torrent. The last 30km is an unrelenting, never-ending, shit fest that could only be topped by finishing off the ride into a sewage treatment works. If you can’t tell the tears for the rain are you really crying? The only thing keeping me going is the promise of a bed, shower and hot meal. Several lifetimes later and I arrive at the unfortunate boutique hotel that agreed to my booking. The shambling, shivering, shit-covered wreck that makes it into reception is a truly sorry sight.

Day 6 – Horton in Ribblesdale, Yorkshire Dales

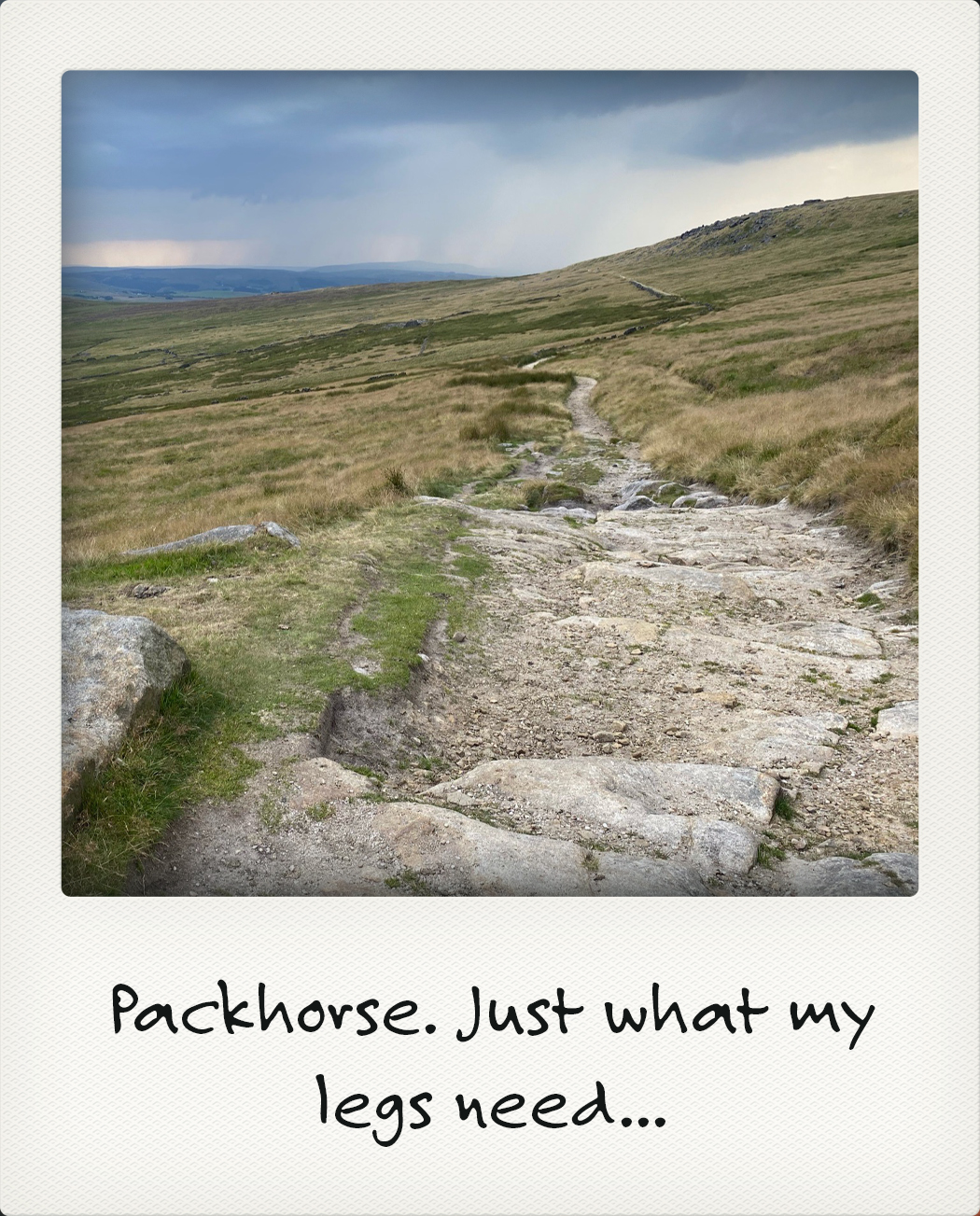

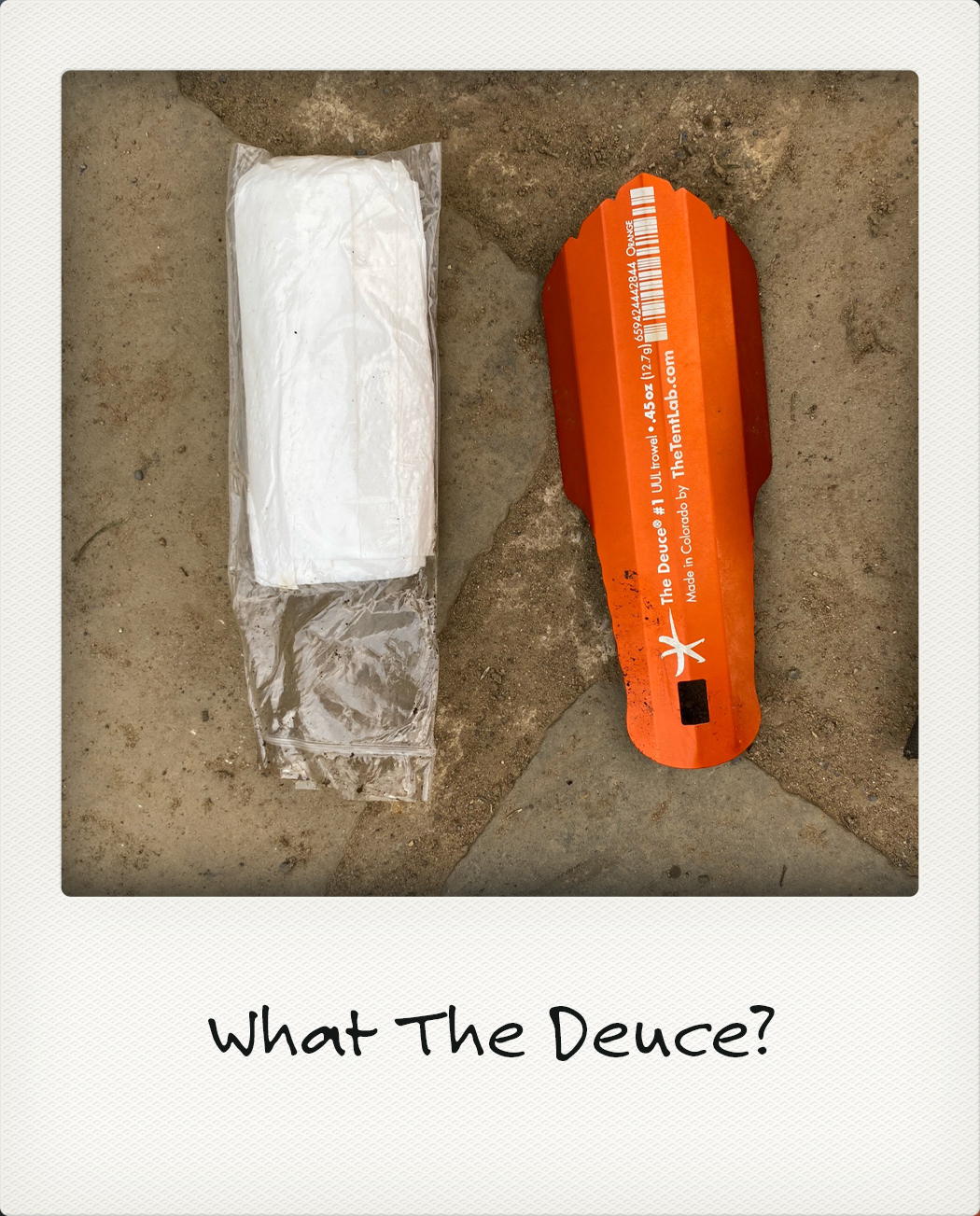

The background tummy rumble has suddenly become a desperate urgency as I frantically unpack the Deuce trowel I’ve been carrying around the last few days. There’s a delicate art to using a coke-can thickness, ultralight trowel to dig a hole in hard ground without folding it into origami, not something to learn on the fly with the enemy, somewhat too literally, at the gates. I frantically saw at the pebble-strewn mud watched on by a flock of the fluffy offenders and I hurl some insults at them while realising the full extent of the Barnoldswick belly.

Day 6 – Hawes, Yorkshire Dales

The best chippy I’ve ever come across. I’ve actually ridden back up the hill to visit having screamed past on the descent before being arrested by the smells emanating from the cottage-turned-fryer. Some things in life are just a bit too good to pass up and despite the checkpoint being just over the next hill I take some down time to enjoy Hawes’ finest delicacies.

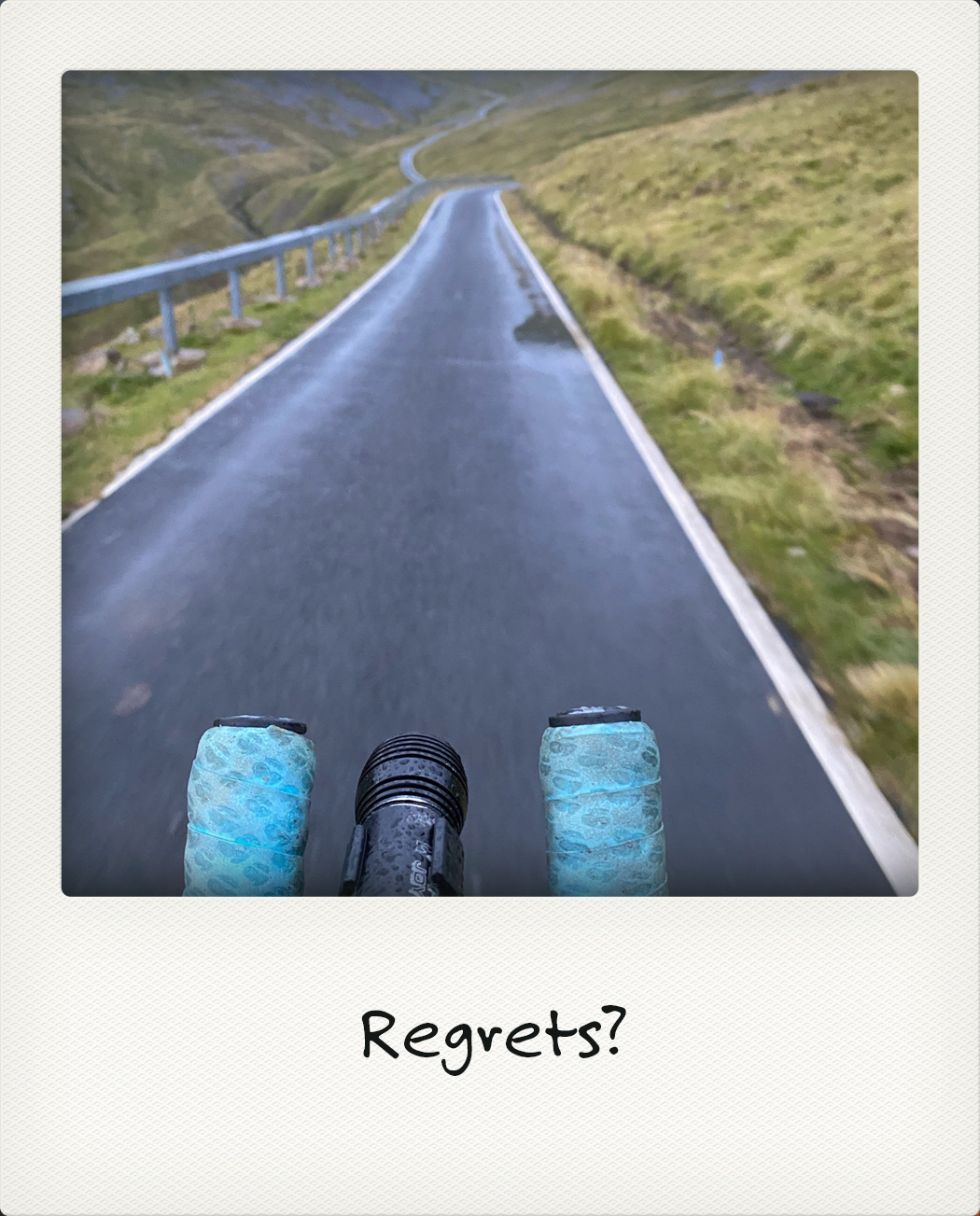

Day 6 – Great Dun Fell, North Pennines

Fortune may favour the brave but the weather certainly doesn’t. Hitting the most exposed part of the climb, the rain lashes across the road as I grind up the desolate tarmac. The clouds have rolled in and visibility at the top of the hill is already looking pretty grim even before daylight disappears. There’s plenty of time to regret the decision – it’s the best plan from a racing point of view, but psychologically it’s left me a bit on the ropes. I’m now committed to the most exposed part of the course for at least the next 25km, and I can’t help but feel that these are the kind of situations that end up making the local news as “Lone cyclist requires mountain rescue after fatal case of hubris”. The situation doesn’t get any better on the descent. Best described as a boggy dark side of the moon, any path that used to be here has long either washed away into the river or become so overgrown as to be unidentifiable. I pick a point on the horizon that matches up with the route and aim for that.

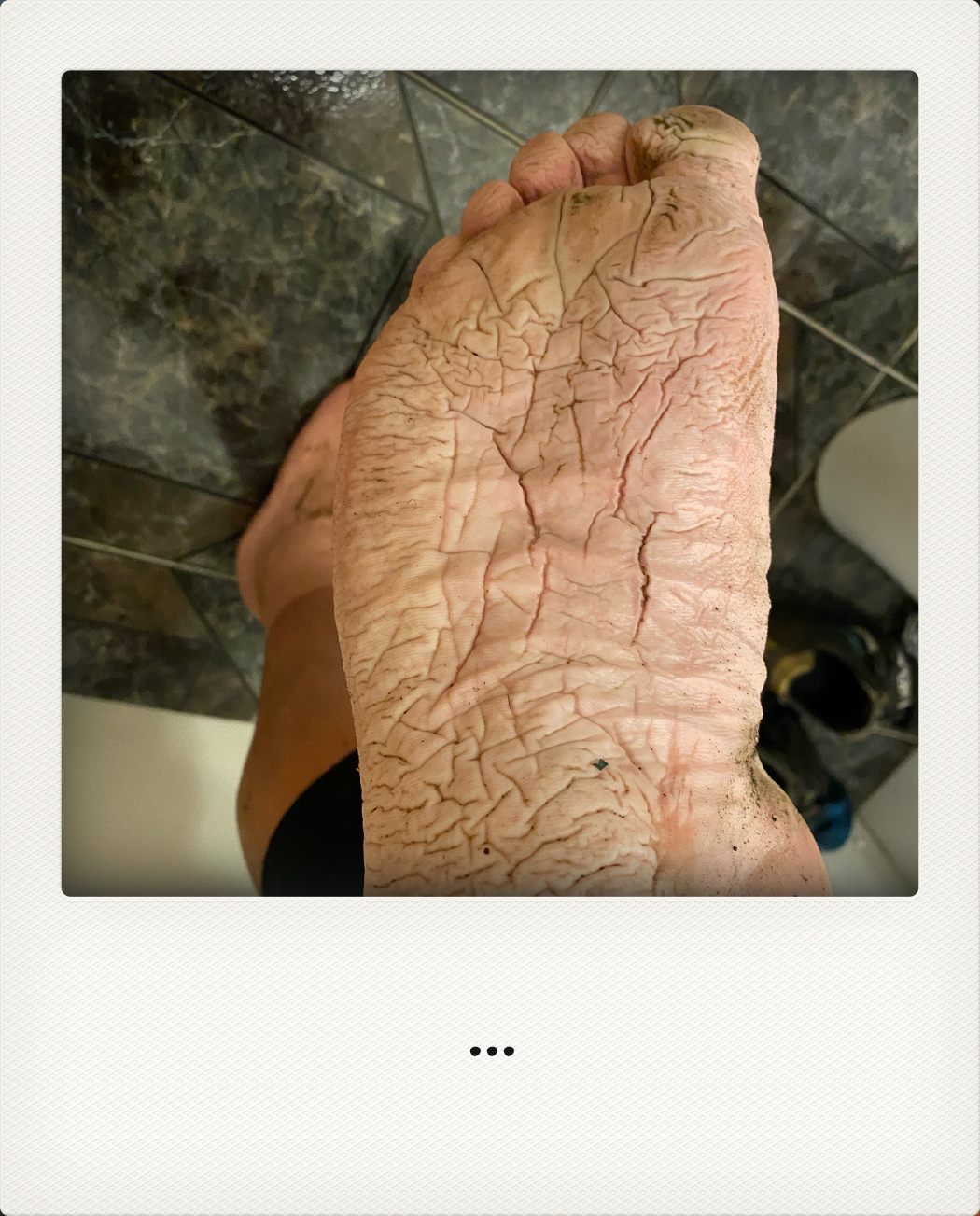

Day 7 – Bivvy bag near Alston, North Pennines

I didn’t realise it was possible to feel so much self-inflicted pain. My Achilles feel like dry, cracked leather in my ankles. The relentless clipping and unclipping into my pedals feel like they’ve torn the rest of the ligaments and tendons in my ankles. Every action brings with it a decidedly pathetic whimper. The morning’s 20km descent into Haltwhistle should have been an easy ride along an old railway line. Instead it’s been a hellish obstacle course of gates, barbed wire fences and a rickety cast-iron stairway too narrow for bike and person. I flip-flop between self-pity and unbridled rage at the utterly absurd challenges on the route.

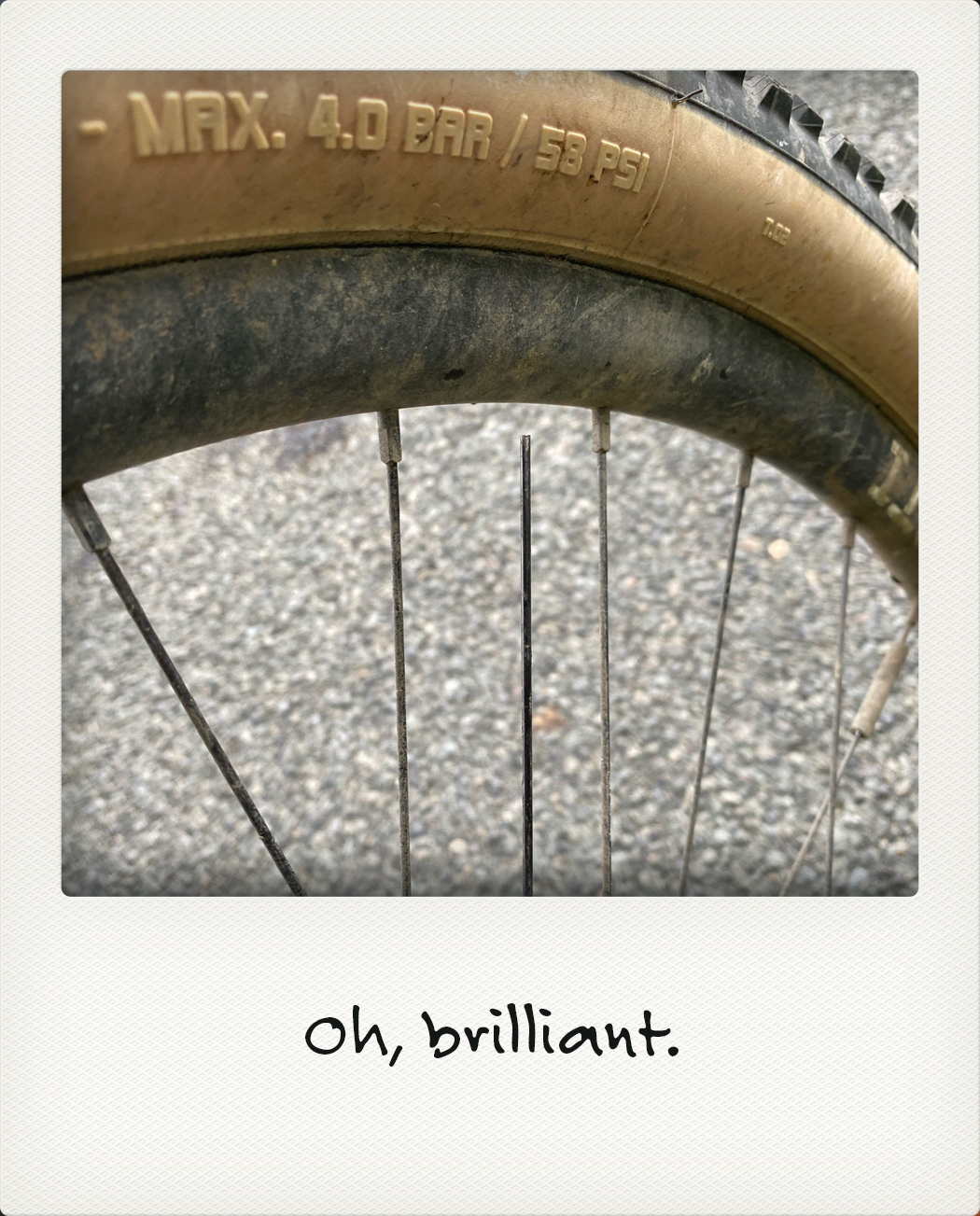

Day 7 – Near Kielder Forest

I take some time to consider how a chain snaps in two places at one time. It’s impressive really. My old friend the bent sprocket tooth has returned too. The angry energy of the morning has dissipated in the barbed wire hurdling and I’m now resigned to not finishing. If I lie here a bit longer I might end up as roadkill which would at least end this misery.

Day 7 – At the Scottish border

The Borders has some truly superb mountain biking trails, unfortunately our route goes absolutely nowhere near any of them and instead opts for the viciously steep climbs of the Cross Borders Drove Road. I phone the Peebles hotels desperate to find a warm room for the night, I can’t even contemplate another night under canvas, before continuing my leaden shuffle up the hill, three steps, rest, three steps, rest. Don’t look up as it’ll just bring you down further. Hunch over the bars and keep going.

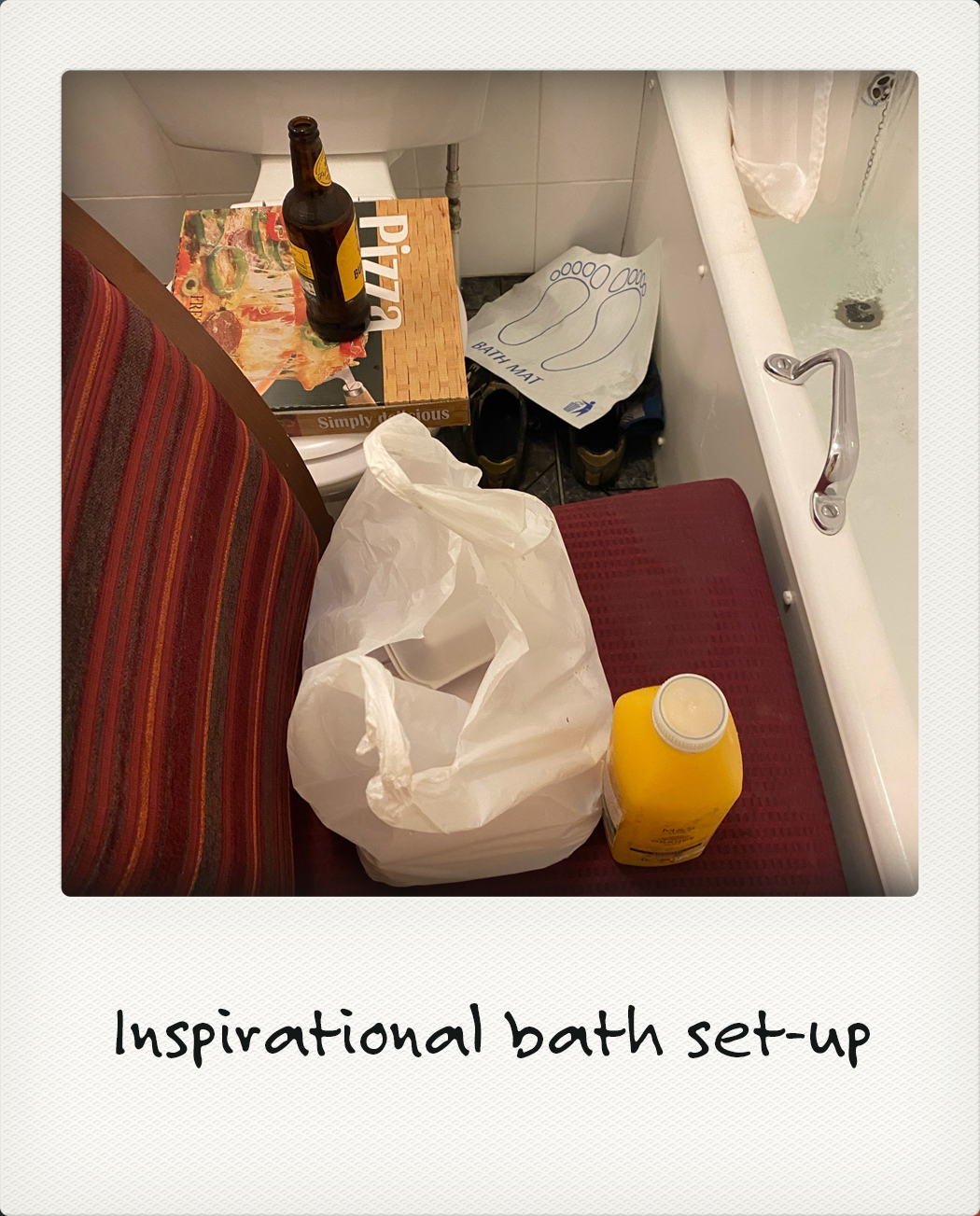

Day 7 – A hotel in Peebles

I’m desperate to take my soaking kit off and just stop moving. I shuffle across the road (from the chippy) to the hotel and the many, many stairs leading to the room. First order of business is to clean and dry my kit, then inspect the damage to my feet. I’m no expert but the pale, peeling skin and persistent tingling has all the hallmarks of trench foot. I pop the last of my ibuprofen, sit in the bath watching Netflix on the phone, drinking cider and eating my now cold pizza from its perch on the loo. For 30 minutes I can almost pretend I’m not in the middle of this unceasing hell and enjoy things before I crawl into bed.

Day 8 – Approaching Glasgow

Drunk with exhaustion, unable to follow conversations or focus on any particular thing, I chew on my lip to take my mind off the overwhelming urge I have to just break down in tears for no particular reason. The dam finally breaks at the sight of an “Allez Opi Omi” sign held by a cycling clubmate on the way in to my hometown of Glasgow, I rush past and round the corner just as the unbridled laughter transforms into heaving full body sobs.

Day 8 – Conic Hill, West Highland Way

The shocked looks and concerned questions from the walkers passing me speak volumes. “Am I lost?” “Unfortunately not.” “Do I need help?” “Not the kind you’re thinking of.” “You should have taken the cyclists’ route.” *barely contained rage*

Day 8 – Rowchoish Bothy, WHW

Grabbing my sleeping kit and some food, I duck inside and try to quietly find some space in the dirt for my sleeping bag. Sleeping area sorted, I take some precious sleep time to put my soaked shoes in front of the smouldering fire and sit, slowly drying off and enjoying the odd comfort of company in the sleeping bodies behind me. A five-star hotel couldn’t come close to this level of warmth and comfort. Suitably fed I fall into my sleeping bag, biting back the scream as both hamstrings cramp and I writhe in pain, trying not to wake up my unwitting comrades in this endeavour.

Day 9 – Loch Lomondside, WHW

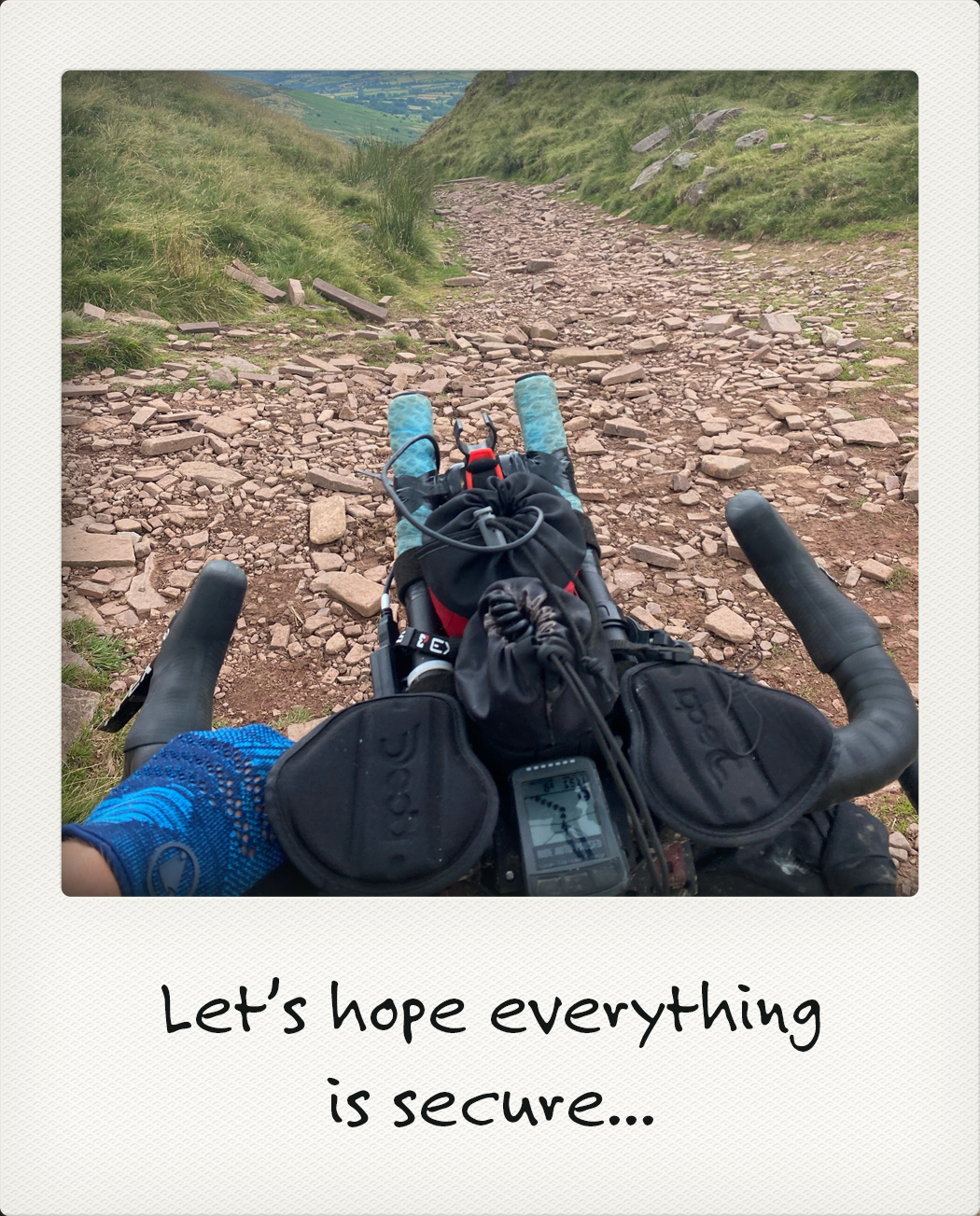

What follows is singularly the worst 10km I’ve ever experienced with (definitely not on) a bike. It’s not a trail, but a series of gaps between the rock fall that sits precipitously on the edge of the loch itself. Passing over and under boulders requires dangling the bike off the edge of drops before scrambling around them. Wooden ladders require cyclocross-style bike carries while carbon soles skitter on the slime-covered steps. Any fall would be either into the loch or boulder field with no access to rescue. The metres crawl past in an unending cycle of adrenaline-spiked fear and baseline exhaustion. Tired mind and tired body don’t mix with these conditions, inevitably I lose my footing dropping down to one of the bridges and end up in the river with bike dangling above. Despite the cold water again flowing through my shorts I take the supine landing position as an opportunity to rest and send some angry messages to the race WhatsApp group at the insanity of including this section. I cringe at the thought of needing Lomond Mountain Rescue, I can’t imagine them seeing the funny side of this if it goes wrong. If there was any other way to get off this trail I’d happily scratch – unfortunately there’s no other way out than moving on. I scream at the top of my lungs, raging at the trail, the organiser and my own stupidity for not questioning this section more when I knew how dangerous it was previously.

Day 9 – Tyndrum

My feet are literally in bits, luckily most of the toes are now just numb but the soles are coming off in sheets. If I keep going I’m going to end up with serious complications. That, and mentally I’m done, I’m not having fun anymore and it’s now just become a march to the end.

Day 9 – Tyndrum

I’ve mentally checked out now and made my peace with calling it a day, looking forward to sitting in the sun and enjoying lunch before getting a train back down the road. I’ll be back in my own bed tonight. So the phone call from Karly is a mixed blessing. While I’ve been trundling on it seems that, with the weather conditions putting the ferry timetable at risk, it’s been decided to bring the end forward to Fort William, 65km away. I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. In the space of 30 seconds I’ve gone from probable DNF to likely winner of the event. Downside, I’ve got to get my wreck of a body on my wreck of a bike and keep pedalling.

Day 9 – Kinlochleven

Running on a raw desperation to not be on this godforsaken course anymore I burn through Kinlochleven for the finish, now running empty on food, water and battery power. Ignoring all three warning signs I hit the final climb like a man possessed and straight into yet another bloody bike push. I can’t even bend my ankles at the angle of the path so I’ve got to shuffle crab-like up the trail, cursing the never-ending climbing of this course

Day 9 – Fort William, 11pm

Running on empty in just about every single way, I’m a shivering wreck by now. I coast through the streets trying to reach the end of the West Highland Way but with my phone battery dead I’ve no idea where the actual finish has been confirmed and there’s no one at the end of the Way south of town. After aimlessly riding around the completely deserted town centre I eventually sit on a stone wall to decant my bags in the hope of a phone charge from my power bank and some form of food. In a glorious bit of irony it turns out the official end was moved from the end I knew into the town centre as the old one ‘was an anticlimax’. Looking to my right, I can see a couple of figures appear round a corner. I’ve spent the last 15 minutes sitting on a wall in direct sight of them less than 200 metres away. I wearily roll across the slick granite to the (official) finish. The cheering and excitement from the little band of supporters is a juxtaposition to my own emotions; I can’t deny there’s a bitterness at how much I’ve had to suffer to get here and I am by my own admission a sore winner. There’s beers, a T-shirt and a chance for a photo. Slowly with the congratulations and cheerfulness of the little band surrounding me I realise how much it means to have friends and family who will stand at 11pm on a rainy Sunday in Fort William, and all across the country, to cheer you on, no matter the stupidity of the endeavour.

Chris’ diary continues for the full length of the trip in the digital editions of Singletrack World 141.

The 2022 Great British Divide starts on 30th July and will finish in Fort William.