Tom is a Climate Change and Green Infrastructure Officer, a mountain bike guide, Cytech mechanic, Greenpeace activist and holds a BSc in Outdoor and Environmental Education and MSc in Marine Environmental Protection. We asked him to take a closer look at Trek’s recent sustainability report.

“Bikes can save the world”, but maybe only the average spec’d commuter ones.

If like me you’re part cyclist and part eco-warrior, Trek’s sustainability report makes for interesting reading. On first glance it’s a comprehensive and excellently laid out report with beautiful photography and graphs showing a high level of critique of their bicycles’ carbon footprints. But what does the report really tell us about Trek’s environmental impact and their commitment to reducing their carbon footprint?

First up, I applaud Trek for investing the time and resources needed to produce a report like this, and for exploring the carbon footprint of individual bicycle models as well as the company’s impact as a whole. They’ve looked at waste, travel, manufacturing, distribution and lifestyle choices.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

How big are the boots?

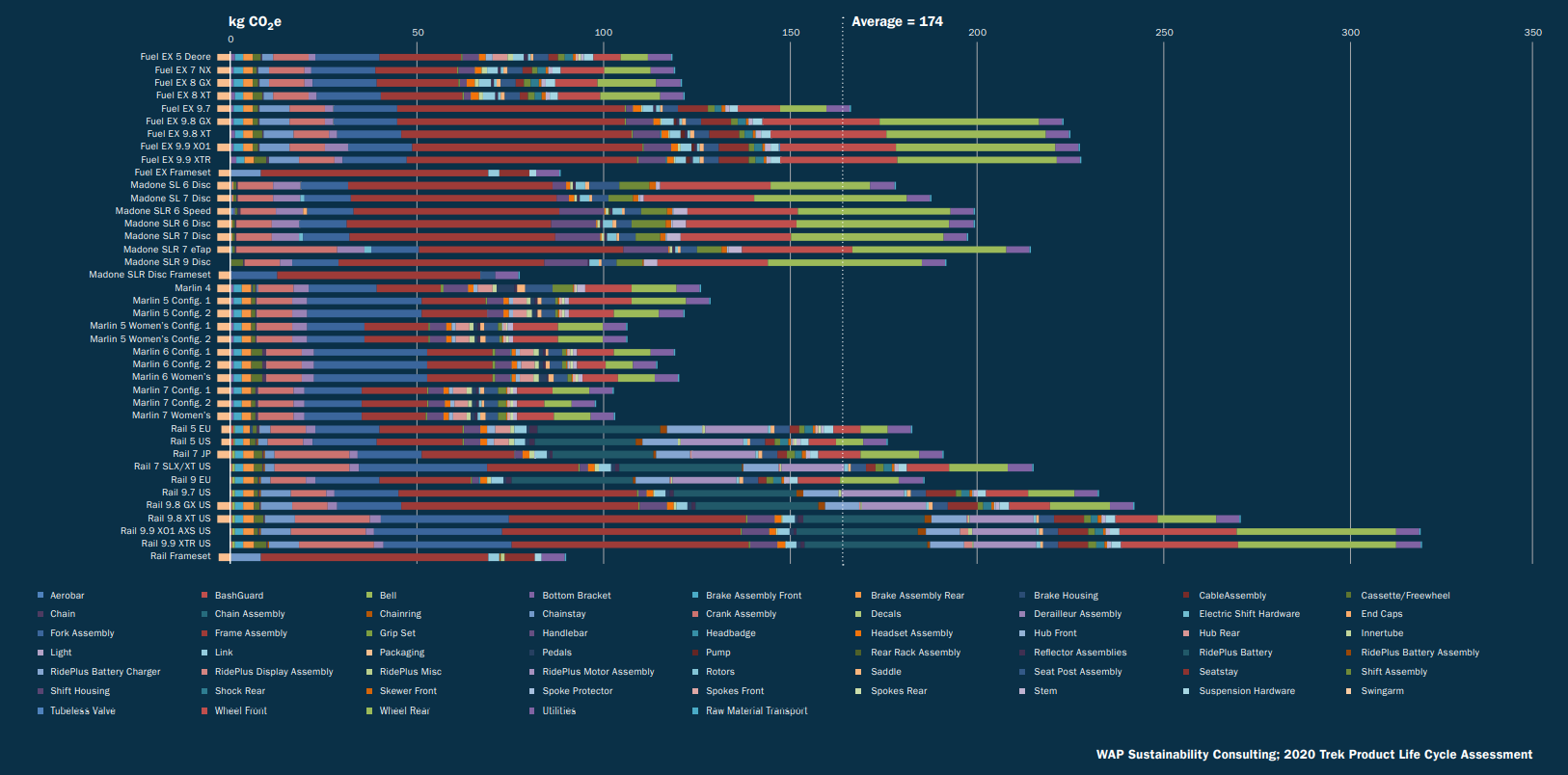

With bicycle manufacturing they’ve gone into depth on the carbon footprint of four of their most popular bike models (the Marlin, Fuel Ex, Madone and Rail) which shows some interesting results. It’s probably safe to assume that like me, you’d guess that the carbon footprint of a heavier, more tech riddled bike like the Rail is significantly higher than the lighter weight, simpler Madone, but by Trek’s calculations the Rail 5 & 7 emits roughly the same CO2 as the Madone 6, 7 & 9. What is interesting is that the average Madone frame emits around double (57kg CO2) than that of the average frames on the Fuel Ex or Rail (27.5kg and 25kg CO2 respectively), hinting that carbon fibre might be a more CO2 costly material (given that all Madones are carbon, where as both aluminium and carbon Rails and Fuels are available, and the aluminium only Marlin has an even lower CO2 cost for its frame at 19.7kg; more on Aluminium later).

Looking more at the disparity in CO2 emissions across the ranges it’s clear that all of the higher spec’d bikes have a higher carbon cost. This makes sense as the higher the spec, the lower the production numbers and the more the exotic materials and processes are likely being used in its manufacture. It seems that by scrapping the elite level bikes from their range, Trek would immediately slash the average CO2 footprint by a significant amount, but are they brave enough to lead the cycling industry away from the ultra expensive ‘dream machines’ that are clearly the biggest culprits of CO2 emissions?

- Fuel 5, 7 & 8 approx 120kg co2, fuel 9.8 & 9.9 approx 230kg

- Madonne – all 175-200kg co2

- Marlin – all 100-130kg co2

- Rail 5 & 7 approx 180kg co2, Rail 9.9 approx 320kg

It’s what you do with it that counts

But maybe Trek don’t need to cut the carbon footprint of bicycle manufacturing because “The good news is that the carbon cost of manufacturing a bike can be mitigated or entirely offset when it’s used to its potential.” That’s a heartwarming concept and frees us of the guilt of buying a new bike, but does it really add up? Trek goes on to identify “If you ride about 430 miles you would have otherwise driven, you’ve saved the carbon equivalent of what it took to make your bike” (see their maths below). But let’s look at those big carbon emitters from their range, the Rail 9.9, Fuel Ex 9.8 and 9.9 and the Madone range – how many of those bikes are being ridden 430 miles you’d otherwise have driven? Is anyone out there using a £10k e-MTB or a £13k Madone SLR 9 eTap to pop to the shops to pick up some milk or to drop the kids at school? (Photos on a postcard or via Instagram please, I want to see a Rail on the school run).

“The math of 430 Manufacturing a Trek bike emits, on average, 174 kg CO2e.

A single gallon of gas emits 8.887 kg CO2e. The average vehicle travels 22 miles per gallon of gas.”

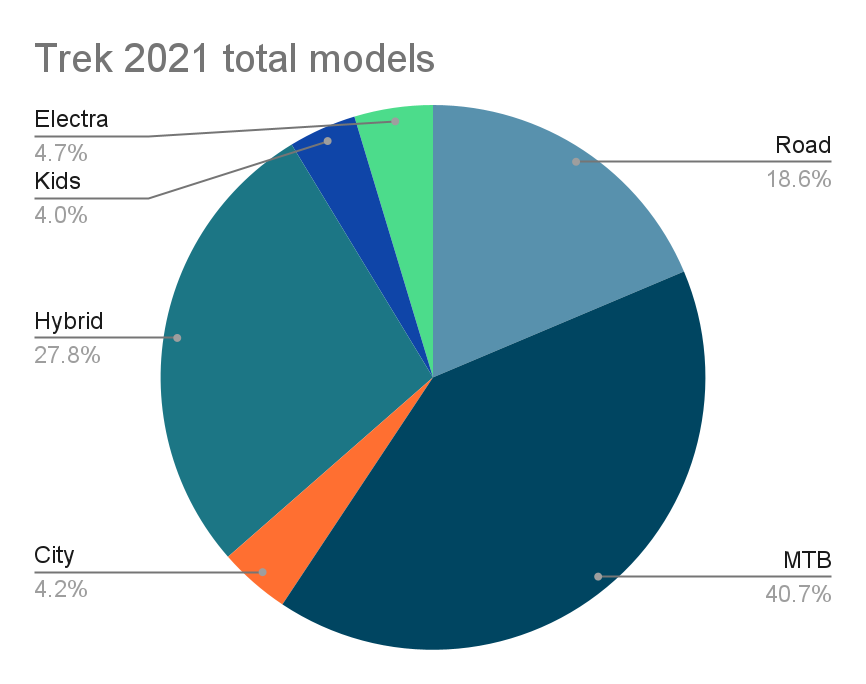

Now Trek won’t tell us precisely how many bikes they make or sell each year*, but some rough maths on their total carbon footprint (300,000 metric tons CO2) and their quoted average CO2 emissions for their bikes (174kg CO2 per bicycle) tells us they make 1.3 – 1.7 million bicycles a year. In order to offset the carbon used to manufacture these bikes, 560 – 730 million miles of car journeys would have to be done on their bikes instead. If we’re generous and assume that every city, hybrid, kids’ and electra bike sold, plus 25% of all MTB and 25% of all road bikes were used for commuting, that still leaves almost half of all Trek’s bikes sold each year not being used to commute at all.

In reality I fear it’s far fewer bicycles that are used in place of cars and at this point their magical ‘430 miles’ starts to fall apart as Trek themselves admit they collect no rider data on how their bikes are used beyond asking newsletter signups what their interest is. For Trek’s ‘430 miles’ to really work out they need 200,000 – 260,000 bicycles a year to be bought new and used full time in place of cars on a 12 mile daily commute, or they need to sell fewer CO2 heavy bikes and invest more in re-popularising aluminium frames, average spec’d bikes and real usable alternatives to personal cars for short journeys.

“Six miles is a sound biking distance that’s manageable in time and effort—and more than half of the transportation-related emissions in the U.S. come from trips under this distance.”

Given the justification for buying a new bike is to ride it instead of driving your car, and that their race team activities emit roughly as much CO2 as ALL Trek Rail bikes, perhaps now is the time for Trek to divest away from elite level sports professionals and start having brand ambassadors and ‘pro’ riders who commute and work on their bikes?

It’d be fantastic to see Trek put some of their expertise into cargo bikes and utility bicycles that allow riders to leave the car at home even when they’ve got kids to drop at school / it’s raining / they live in a less urban environment. The one huge barrier that no one seems to be adequately addressing yet – neither bicycle manufacturers, employers nor local authorities – is how frequently a cycle commute leaves you sweaty, dirty and without adequate changing areas before starting work. Can we ever have a usable bike that keeps us clean on a winter morning in the UK?

Cycle, Recycle, Recycled Cycle?

“Historically, Trek’s aluminum model bikes have been composed of 30% recycled metal” while “recycled aluminum retains the same structural integrity no matter how many times it is recycled.”

It’s no secret that aluminium makes very good bikes while steel is favoured by many, especially those looking for a super robust and long lived bike (cargo / utility / commuters?). Both metals are repairable and recyclable and while they do use a lot of power to recycle, power can be produced sustainably but new raw material cannot. The weight and performance differences between aluminium and carbon can, and will, be debated endlessly, but I’d argue there are VERY few riders who would be genuinely disadvantaged in their commuting or recreational riding if they had to ride an alu bike. Trek claims second hand aluminium is getting harder to source which makes me wonder if it’s time for them to take a leaf out of Pataongia’s book and take back old unwanted frames and bikes to keep that resource within the cycling industry?

Post consumer waste is one area Trek don’t look at, but it’s a significant one, especially given the rise in e-bikes, failed motors, worn out batteries and the tons of bicycle tyres that get discarded every year. Velorim are doing all they can to keep bicycle tyres out of landfill but there’s a clear opportunity for one of the big bike brands to lead the way with a post consumer reuse or recycling project. Hopefully the next sustainability report we see in the cycling industry will look at the full lifecycle of our bikes and envision a cradle to cradle approach wherever possible.

“Goal: Double the amount of recycled material in our products by 2022”

Trek commits five pages of their sustainability report to reducing waste, which while admirable seems a bit late in the game. Other bike manufacturers have gone zero plastic and 100% recyclable boxes already so while I applaud Trek moving in the right direction it’d be great to see a lot more progress, a lot quicker and across ALL their bikes.

“…begun rolling out a 95% recyclable exterior bike box for many of our non-Project One top tier models.”

A big win that Trek has implemented is the consolidated shipment method of getting product to the detailer. By holding all orders for a once a week dispatch day Trek has seen 40% of orders now be consolidated together meaning fewer vehicles doing fewer deliveries but customers still getting their bikes and spares the same week they otherwise would have done. This is a huge step forward in reducing the shipping CO2 emissions and it’s exciting to see if this approach can be adopted by the wider industry. Hopefully Trek will be open to sharing their experience of consolidated shipping and work collaboratively with other brands to identify best practice and quick wins for reducing CO2 emissions in the supply chain.

“…the most impactful thing we can do is also the simplest: get more people to ride” (the bike they already have).

A Step Forward, Now Let’s Run

Trek has done what no other major bicycle manufacturer has done (yet) and this report represents a huge step forward in the cycling industry. That said, it cannot hide the fact that the industry is still pushing high spec, high tech, low repairability and mass consumption. Until the industry, or one of the major players, takes the bold step away from high end models and constant updating of bikes we will never get a real grip on the spiraling CO2 emissions of our sport. E-bikes need motors and batteries that are repairable in the local bike shop, roadies need reminding that a £4k bike is almost as fast as a £13k bike, but a damn site more environmentally friendly, and we all need to buy less, repair more and keep the bike we have longer.

Reducing the ever changing ‘improvements’ of new standards would go some way to reducing waste as riders could upgrade just the parts that need changing and reuse parts off their old bike, while making everything repairable and spares available would cut a huge amount of CO2 from the industry. Consumerism and disposability are the two greatest issues, neither of which can we cycle our way out of, and no matter how many trees you plant, keeping your current bike will always be a better option than buying a new one.

Trek has led the industry in producing this report and I look forward to their next update and reading similar reports from the rest of big players in the bicycle industry. Despite my criticisms I applaud them for getting this report published and would welcome the opportunity to explore their data further.

*Trek did not provide any additional data beyond what is included in their sustainability report which is difficult to determine precise values for. I would encourage them and all cycling brands to be more transparent when publishing sustainability reports in the future and apologise for any rough or inaccurate maths in this article.