It’s impossible to mishear the noise in the woods. A commotion growing bigger and coming nearer, the sound turns the heads of scattered spectators on its way through the terrain. A figure flashes between the trees, its arrival only preluded by the sharp warning of whistles. A blur appears, carrying a speed that is near incomprehensible. You can hear that it is fast.

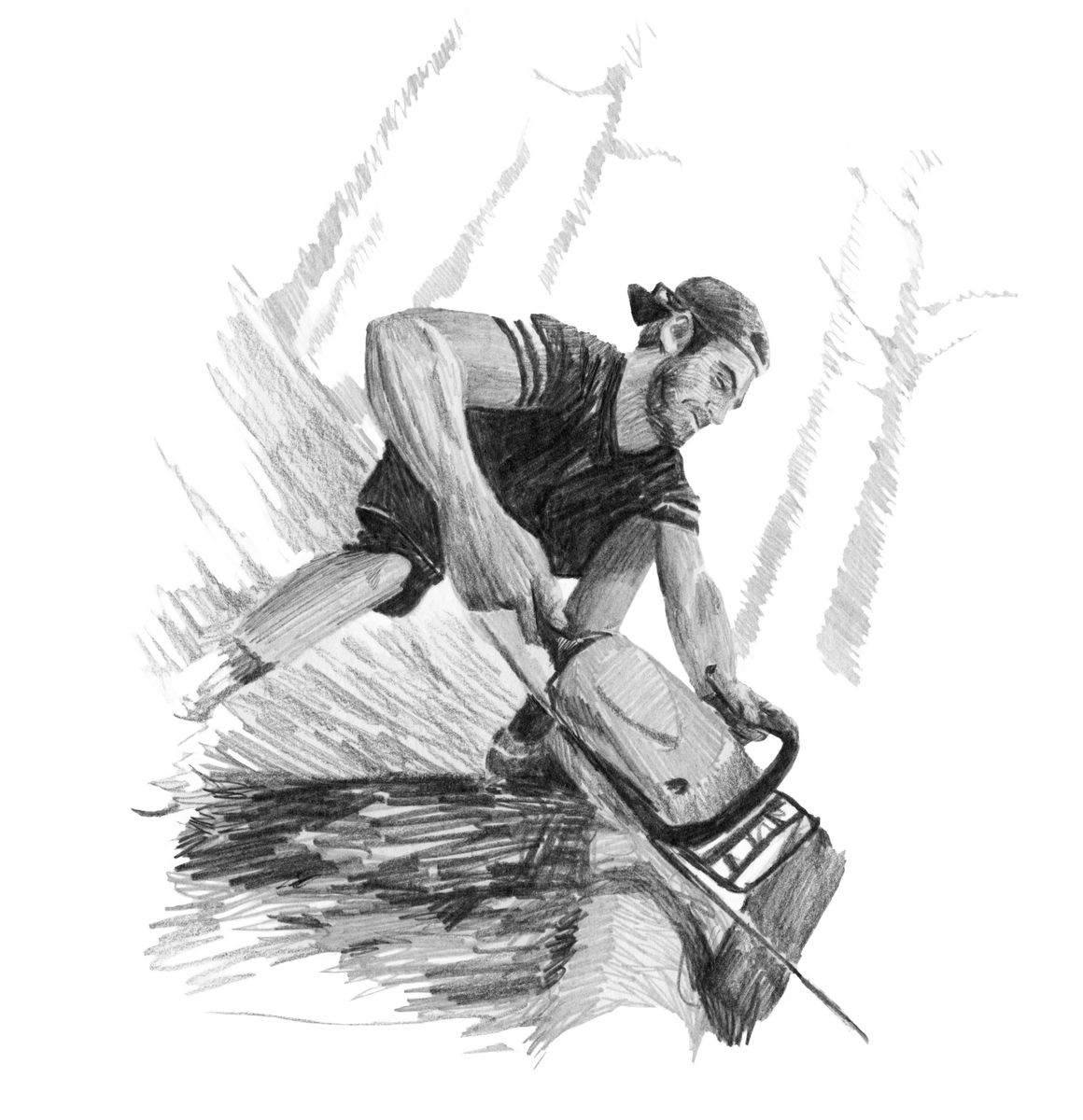

It’s July 2021 and trail builder Léandre Alegri witnesses first hand how the noise materialises into a downhill rider charging down the newly cut World Cup track, hunting in the margins of time. The riders are pushing hard and the track responds by almost becoming an entity of its own, getting out of its way for no one. There seems to be a tug of war between the riders and the ground itself as the weekend progresses. For each run counted, the earth unveils yet another one of its riddles that the riders will be forced to decipher. Roots previously stealthily hidden in the earth suddenly appear in the ruts that become deeper and more treacherous. Turns that once held support suddenly bottom out under the increasing pressure from the racers.

Beyond the hustle and bustle of the event, Léandre looks back on weeks of work creating the course . Having the track located in the alps meant that Léandre and his team had to surrender to the conditions.

‘We started working on the World Cup track in the beginning of May. Throughout May there was snowfall on Mont Chery which turned to a rain that was present during the entire build. It was very difficult to work the ground in to its final shape because of the wet conditions. When the rain was too heavy we switched from digging to cutting wood.’

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

With a crew of just three people, creating the World Cup track was a daunting task. Léandre’s experience in building came very handy for this massive project.

Growing up in Carcasonne, Léandre started building his own courses and features at the humble age of twelve. As he moved into his teens, digging and shovelling advanced once more with a few years spent on a BMX. However, the mountains did not release their pull, and by seventeen Léandre was once again back on big wheels, racing and competing in the French and European Cup. As so many have experienced, racing is a double edged sword. The rush of competition and success can quickly be shadowed by the risk that is the inevitable companion of competition. When injuries became too frequent, Léandre laid the number plate to rest and looked at the mountain anew. Staying connected with nature, Léandre rediscovered his friendship to the woods on his mountain bike. Here he became a native to both building and riding, nurturing a creativity that would echo on the tracks he would work on in the future.

Over the years Léandre has seen a massive evolution in how mountain bikes perform. This has provided new challenges in how trails and courses are designed, with racetracks being at the forefront of what the riders should be able to handle. So how do you stay in front of this progression from a building perspective? When building the racetrack in Les Gets, Léandre emphasises the importance of a collective input when designing a race track.

‘The development of a race track is rarely decided by a select few individuals. During construction it is vital to have several different riders testing the track to receive a wide range of experiences of how it rides. Analysis of the track starts during the race and continues after the race is finished. Feedback is gathered from riders, the organiser, UCI and event crew and is then made in to changes that help evolve the track.’

The race tracks must evolve, not only for the sake of progression but also in terms of safety. In 2019 the Les Gets World Cup track had some issues with one of the final drops which (amongst others) took out Rachel Atherton with a torn Achilles tendon. The challenge of pushing the sport forward is balanced on a thin line when building for racing.

‘The near flat-jump that ended the 2019 course was indeed unpleasant and poorly designed. This was revised for 2021 with a completely different final section leading to the same arch to the finish as last year.’

‘It’s good to work towards safer tracks for the riders and the spectators, although one has to remember that downhill is an extreme sport that has the rider going very fast through natural terrain facing difficult obstacles. When you build the track you have to bear in mind where the highest speeds are going to be reached and to make sure that the track stays open in those places. Conversely, in places where there are obvious dangers the track need to be built slower and provide maximum protection in areas around the track.’

In the end, the race itself will decide which parts of the track work well. When judgement is passed, there will be no distinction made between the parts of the track that were easier to build and the parts that required hundreds of hours of manual labour. As frustrating as it sounds, this is is the reality for the trailbuilder.

However, building a World Cup downhill track isn’t just about the physical effort. With the World Cup only consisting of seven races, each venue is extremely important and stakes are very high for the location to deliver a World Cup worthy track and event. The crews responsible for building the racetrack obviously bear a huge chunk of this burden as they are well aware of the massive audience that will be watching the event worldwide.

‘The pressure was quite heavy. We really did not want to miss this chance to build a successful track. In the end it was a huge relief and a great joy that the track is was so appreciated by everyone.’

Judging from the comments in post race interviews, the track was very successful, receiving an abundance of praise from the riders. The vast array of line choice was something that really stood out, which made for an interesting race for both riders and spectators.

No doubt this is setting Leandré’s mind at ease with the arrival of Sunday, finals day. Standing trackside, Léandre hears how the clatter of wheels against dirt is mixed with the howling of chainsaws, trumpets and screaming fans. The noise transforms into a song that rallies the heart of a mountain bike community slowly becoming unlocked from a pandemic world.

At home we are riding with our heroes, imagining what it might be like. Our hands grasp those mental handlebars and take on the turns, roots and jumps of the track. We marvel and compare, throw banter and dream. Unknowingly, we are creating the net that makes our culture and community so solid. In days to come the World Cup track in Les Gets will be ridden by one rider at a time. On this Sunday, it is ridden by a select few, and thousands all at once.

- Big thanks to Leandré Alegri for his thoughts on building race tracks and photographer Valentin Ducrettet for the stellar reference photos.

- Anders’ illustrations have been made in pencil, acrylic and oil paint.