This week, Ibis Cycles has launched the Ibis Exie (‘X C’ – geddit?) cross country race bike. It’s a 120/100mm carbon fibre race bike that saves weight over the already light Ibis Ripley. What is interesting about it is the fact that the whole size range is going to be built in the Ibis headquarters in Santa Cruz (yes, that Santa Cruz – it’s a short potato-cannon range from Santa Cruz Bikes’ factory too). Previously, Ibis had experimented with US production by building the smallest size carbon Ripley Mk4 in-house. But with this announcement, Ibis is making a bold move towards making some of its bikes on US soil.

Making bikes in the USA isn’t a new thing, but the carbon fibre revolution has taken many bike companies from hand-welding the good ol’ ‘Murica to (equally hand-made) carbon fibre frames made in Taiwan, China or Vietnam. Some companies like Santa Cruz and Yeti went years ago, followed by Intense (to much grumbling) and even, reluctantly, Turner, which held on to the very end, but still had to buckle.

It seemed that, once the aluminium frame buyers switched to carbon, that the bike companies had little choice but to transfer manufacture to the Far East. Despite the initial high cost of moulds (a different one was usually needed for every frame size or geometry tweak and even then could only make one frame, or fewer, an hour) once that production was established, the cost per frame often went down, due to the lower labour costs in Asia. However, it wasn’t all plain sailing as with such remote production, frame revisions often took a long time, with frames (or engineers) crossing the globe several times during a model’s development.

Although Taiwanese (and other) factories usually had greater experience of making carbon frames, the production process wasn’t super-skilled. The economies tended to come down to the amount (and cost) of labour in carbon’s very labour-intensive processes. Some US companies, like Alchemy and ENVE chose to make the majority of their products in the US, though with a price-hike over their Asian counterparts. However, judging from sales (in the bicycle world, but also in other precision manufacturing industries) it seemed that when presented with the choice between a US made frame and a cheaper, Far Eastern made one of equal quality, most consumers vote with their wallets.

Latest Singletrack Merch

Buying and wearing our sustainable merch is another great way to support Singletrack

The problem that Ibis (and other ‘made in house’ companies) faced was to make the same production quality frames, while paying Western-world wages. For companies like Hope Technology, the arguments are simpler. Hope reckons that the machines it uses are the same CNC machines as everyone in the world uses. While Western wages are higher, Hope reckons that its efficiencies in batch-making components, along with much cheaper (and quicker!) shipping outweighs the cost benefits of overseas machining. If the raw materials and the machines cost the same, then savings on time and efficiency can outweigh paying the workers that bit more.

Hope reckons there’s no disadvantage in making its products in the UK. And with the time saved in the to-and-fro of overseas product development, it can make in-line changes to products in a matter of days instead of months. If there’s an issue, or a clever idea, a new component prototype can be designed, made and ridden in a few days. And any feedback can be done by walking across the office, instead of waiting for the timezones to line up to make your Zoom chat possible.

Orange, too, reckons that with smart manufacturing keeping time and wastage to a minimum, domestic manufacture has many advantages. And we’re starting to see it more and more, with Cotic and Stanton offering UK-made frames and even more companies looking towards that more agile way of working. Ibis isn’t alone, either, with an in-house carbon facility. Neighbouring Santa Cruz bikes made Danny MacAskill’s trials frame in-house and just over the hill, Specialized has the ability to make carbon prototypes (and can even X-Ray and CAT scan frames) in-house.

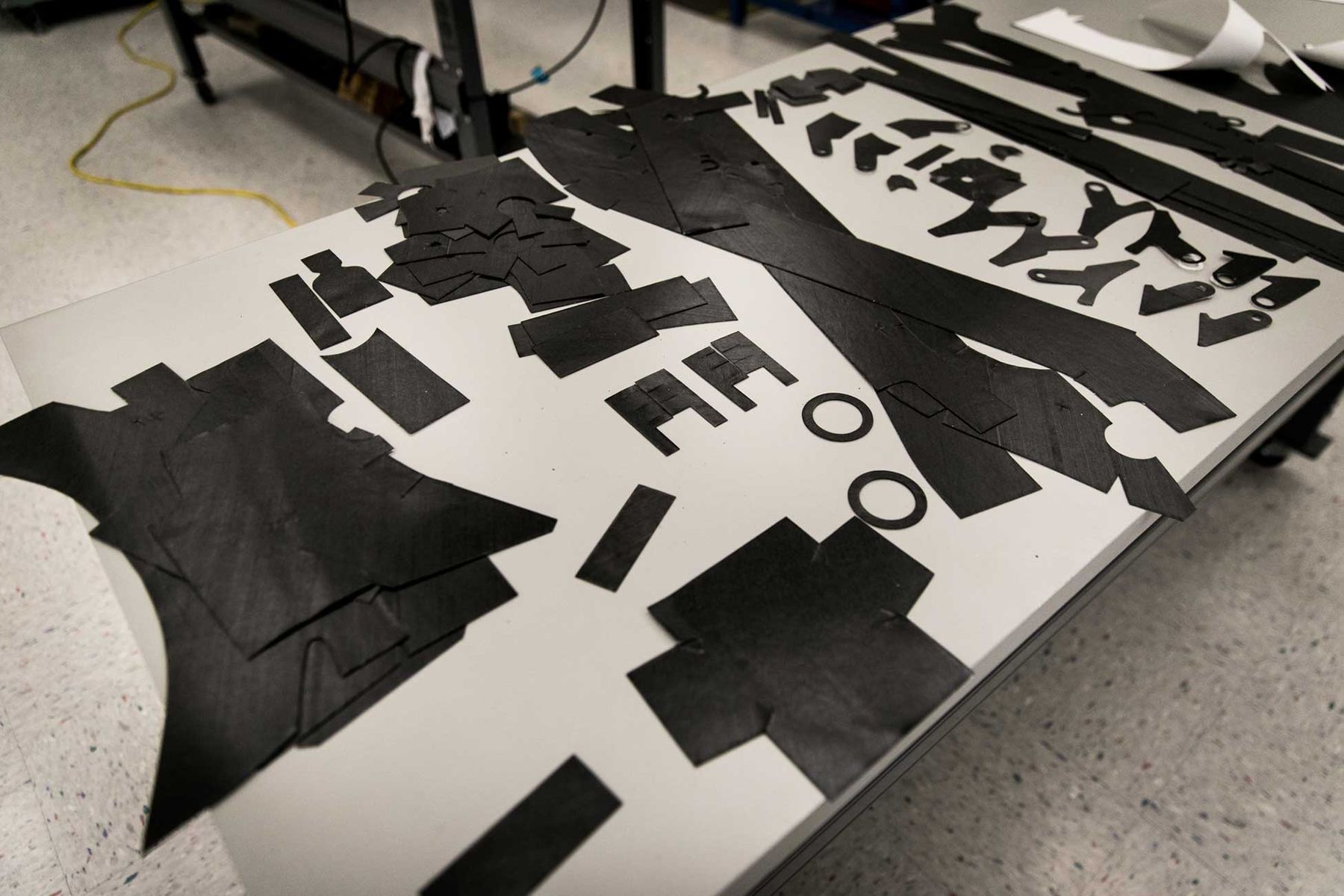

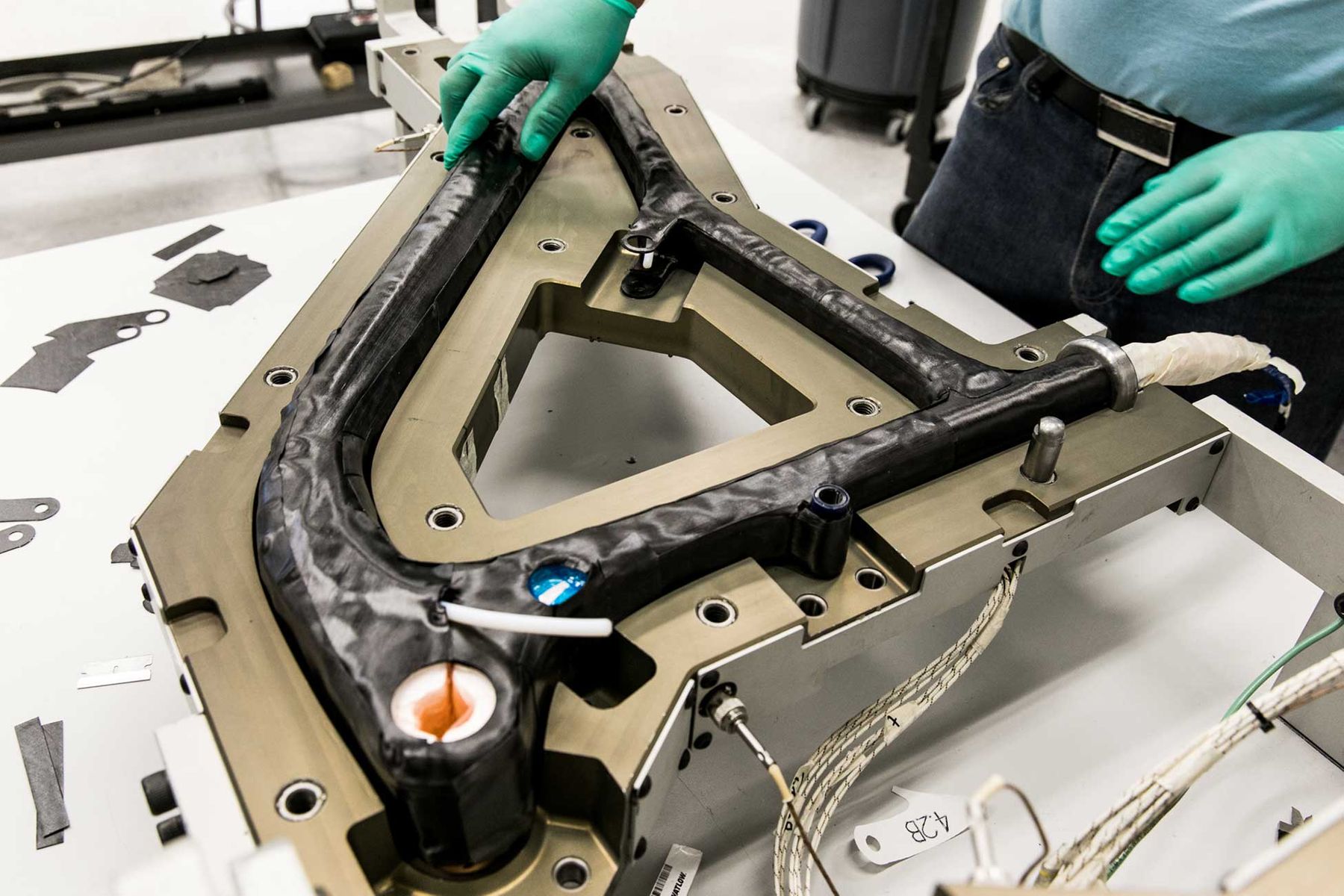

And so it is with the new Ibis Exie – a home-built production frame. As you’ll see in the video below, Ibis had the design, but had to work out how to make it smarter and simpler with the more expensive American labour on hand. This involved clever carbon cutting, to make the layup sheets far closer to the final shapes needed, rather than the jigsaw-style assembly used in the Far East, where greater numbers of simpler shapes are used to make up the raw frame ‘tubes’ before going into the mould.

Ibis certainly has confidence in the new Exie. There’s a seven year warranty on the frame, despite it coming in at less than two kilos…

Here is the Ibis ‘How we do it’ video.

Is this new, smarter way of working going to see more companies looking to make in-house? What about when the Taiwanese adopt the same smart-working practices? Is the volatility of international shipping (thanks, EverGiven) and cross-border taxes (thanks Brexit) going to be enough to persuade shoppers to spend a little more for a UK (or US)-made product they can get warrantied quickly if needed?

With the new Lotus and Hope Track Bike for the Olympics, perhaps we’ll see a surge of interest in domestic carbon, titanium and even steel bikes made in the country. Or perhaps everyone will just continue to thumb down the page until they get to the cheapest, on-offer price of what they want and buy it regardless. Let’s see…

Join our mailing list to receive Singletrack editorial wisdom directly in your inbox.

Each newsletter is headed up by an exclusive editorial from our team and includes stories and news you don’t want to miss.