We get a bit hot under the collar over this linkage driven high single pivot steel full suspension prototype – because that sentence is like bike nerd bingo.

Oh my, what do we have here? It’s like all our nerd buttons are being pushed at once. Where shall we start? With the shiny steel aesthetics? The steam punk drive train? The what’s-going-on-there suspension platform? The beautiful mitres and construction process images? Choices choices. So much stimulation of the nerd nerves. Quell that quivering heart and just let your eyes roam over a few images.

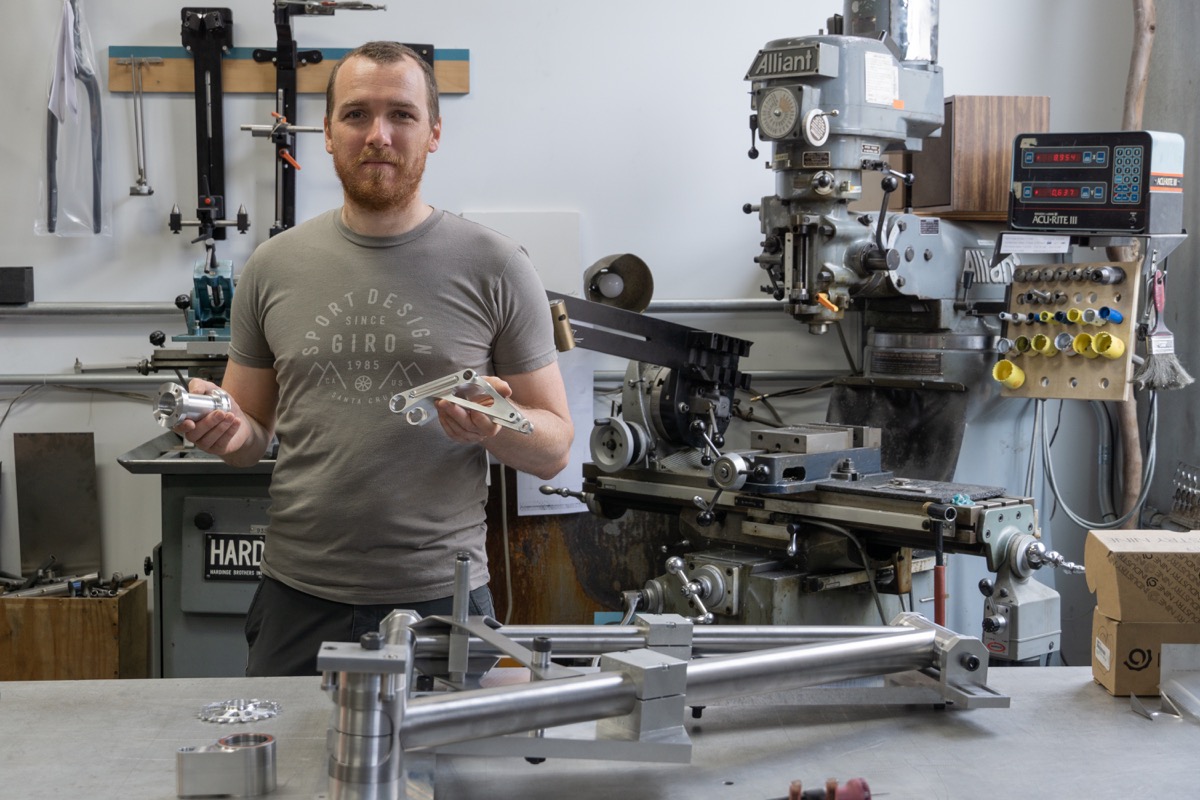

This is the brain child of Evan Turpen, a former pro rider from California. He says he’s no engineer, but he is a bike mechanic and he’s looking to start his own bike company. What you see here is his first proof of concept prototype with a patent pending full suspension design.

Patent Pending Suspension Platform

The suspension design is a linkage driven high pivot with idler, which he has yet to come up with a catchy name for. However, he claims it’s nothing like other linkage driven single pivot bikes. Of course he’d say that – it’s marketing 101. So what are his claims?

‘It is “patent-pending” so the provisional patent (which is not published) has been submitted so I can apply that priority date towards the final non-provisional patent once that is granted. I have a little while left before I need to submit the non-provisional patent. I wanted to ensure that it rode correctly first, before spending all the money on the final patent.‘

‘The suspension design has extremely stable anti-squat in every gear at and around sag. This makes the bike pedal very good no matter what gear you are in and what sag setting you prefer. This current bike has exactly 100% anti-squat at sag (30% of rear wheel travel) in every gear for the center of gravity position I designed it around. To the best of my knowledge no other rear derailleur driven high-pivot bike does this. And I don’t know of any non-high pivot bikes that do this either.‘

‘It also sees 100% anti-rise at sag which means the bike is extremely stable under braking. You don’t have to shift your weight back to counter braking forces. The leverage rate is also tuned exactly as I want it for a very supple top of stroke with great bottom-out resistance and not too much ramp that it adds deep stroke harshness. And then there’s the rearward axle path… it makes this bike carry speed really good! It is amazing in the rough!‘

He thinks that other companies using linkage driven single pivot systems are accepting compromises in performance, particularly too much anti-rise and too much or too variable anti-squat. Since he hasn’t come up with a name yet, may we suggest taking a leaf our of Dave Weagle’s book? The ET-link might do, but how about the EPSILON: Evan’s Perfect Shiny Idler Linkage Of Niceness? OK. Maybe not.

Anti-squat and Anti-rise

He claims this design has 100% anti-squat at sag in every gear combination at 40mm sag, with extremely small variance in the anti-squat percentages in and around sag. Wherever you set your sag between 20%-50% sag will still give close 100% anti-squat. The result? ‘It pedals like a rocketship!’.

It also has 100% anti-rise at 30% sag (although he says 30% is his preferred sag, you don’t have to stick to that) which means braking forces will not compress or extend the suspension.

‘It’s just stable. Watch an F1 car braking from 200mph to 40mph and then back on the gas again out of a tight corner. It doesn’t move. It doesn’t dive. Just pure drive. That’s what this bike does. And beyond that, the leverage rate that I designed on this bike makes its 140mm of rear travel absorb bumps and carry speed better than a 160mm bike.’

Leverage Rate

The leverage rate is somewhat progressive, at 25%.The curve is somewhat steeper at the top, which should give small bump compliance, and while the curve is fairly flat at the end of travel, the 25% progression should be enough to mitigate any bottoming out issues. In addition, the curve is very even, meaning it should be easy to tune the shock to your requirements.

With this level of progression, it seems like a good contender for a coil shock – maybe one with a hydraulic bottom out mechanism to make the ride super plush.

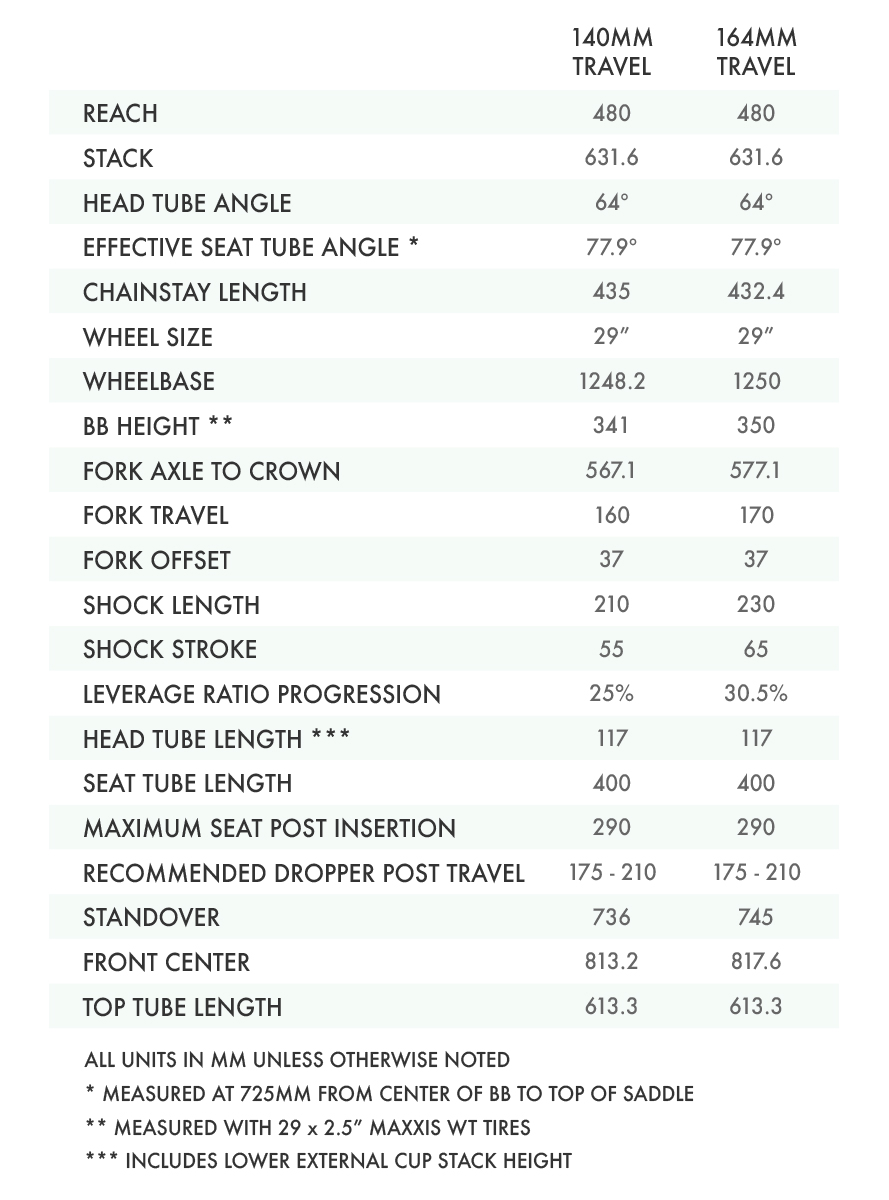

Evan says: ‘There is just the right amount of progression, 25% in the 140mm travel setting and 30.5% in the 164mm travel setting making it fully compatible with coil and air shocks. So far I have only had to use one volume spacer each in both Float X2’s to achieve a nice bottomless feeling. Almost all bikes I’ve ridden in the past have needed lots of air volume spacers to get enough ramp up. This bike doesn’t need that, which is a very nice change.’

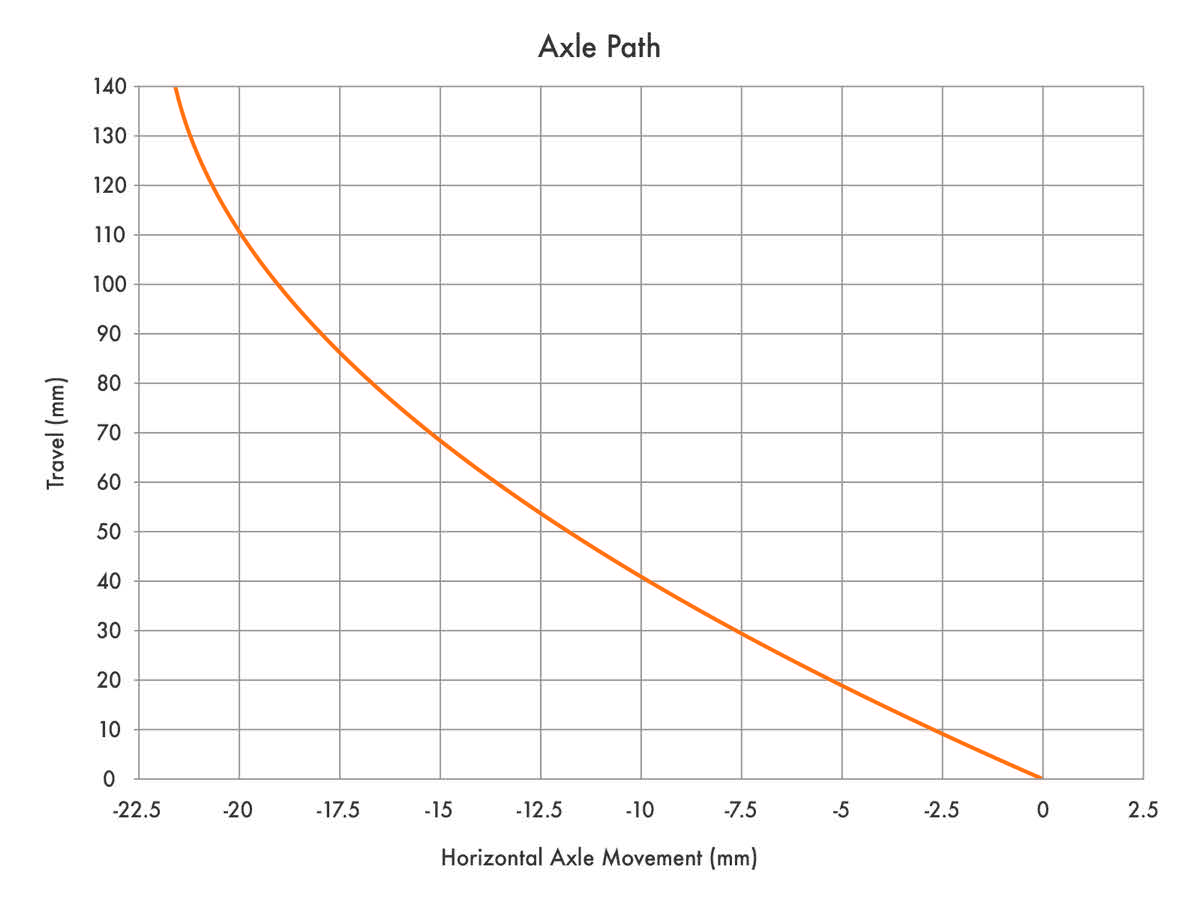

Axle Path

The consistent rearward axle path is akin to that on a Forbidden Druid, and should allow the wheel to move with impacts, maintaining speed.

Ok. Is that enough graphs? Shall we get back to the pretty stuff?

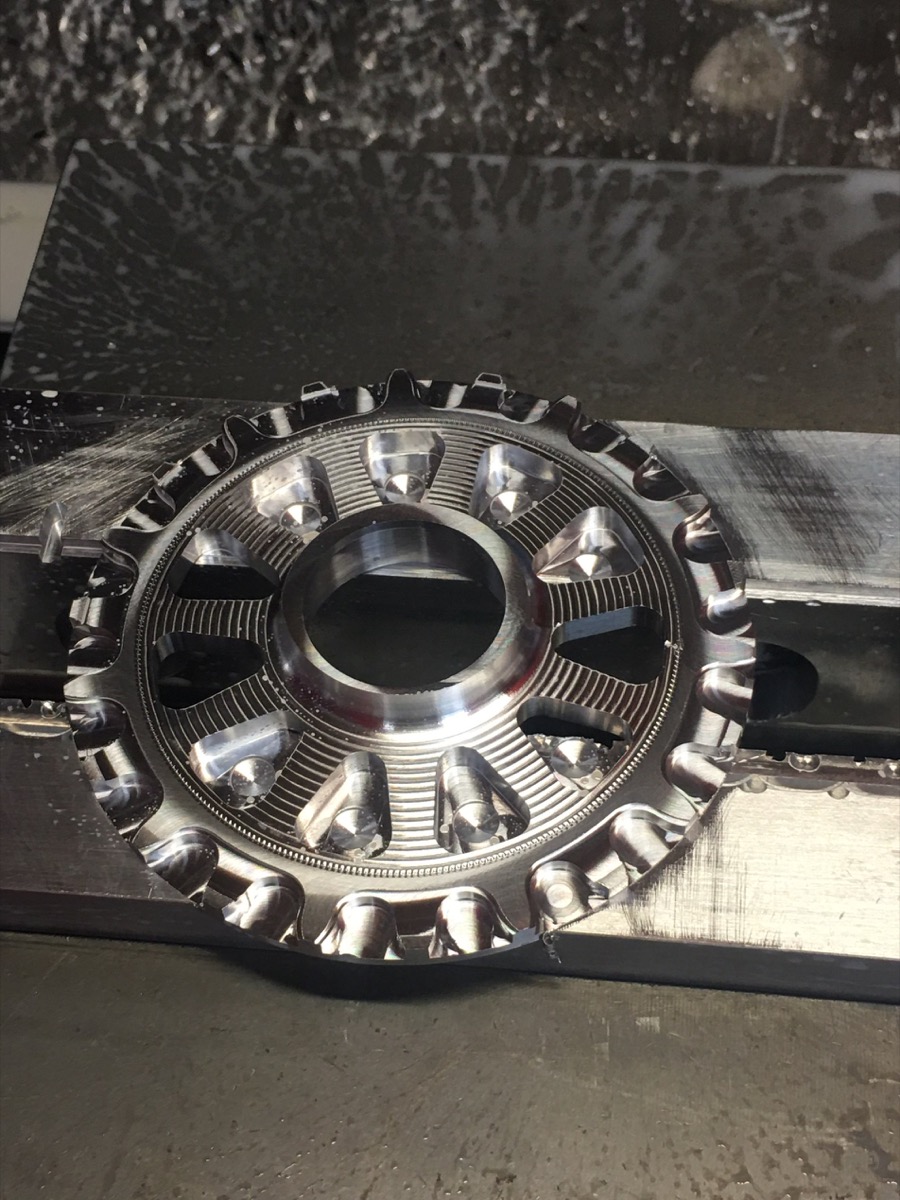

The Idler

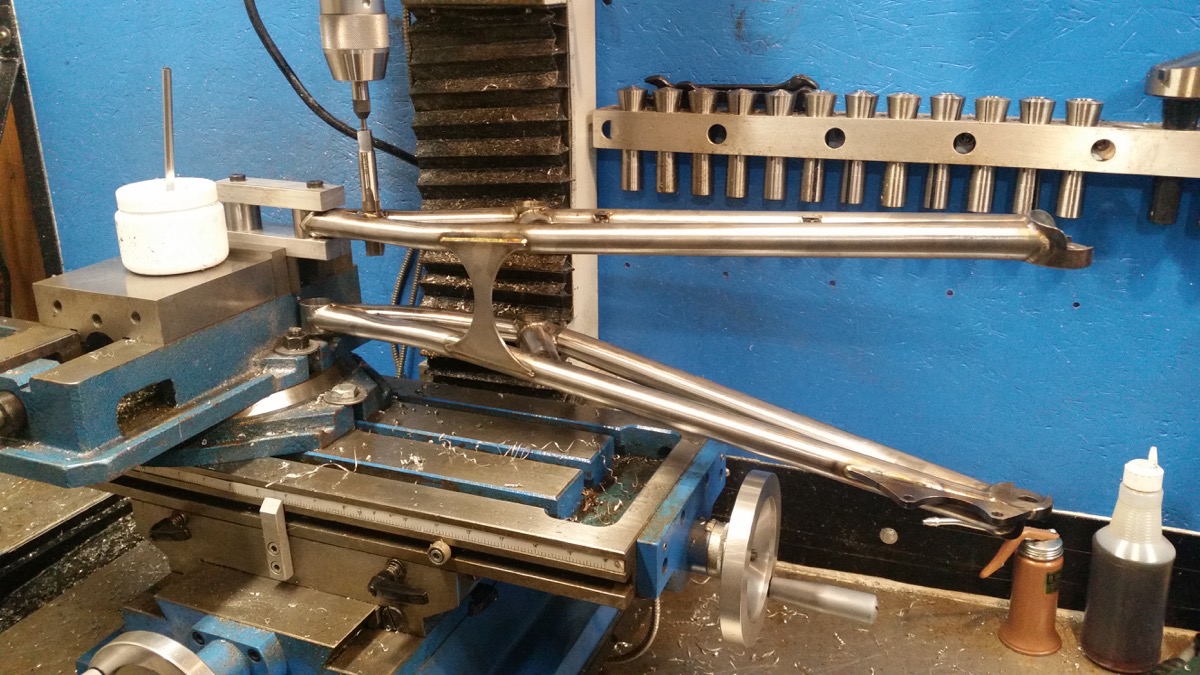

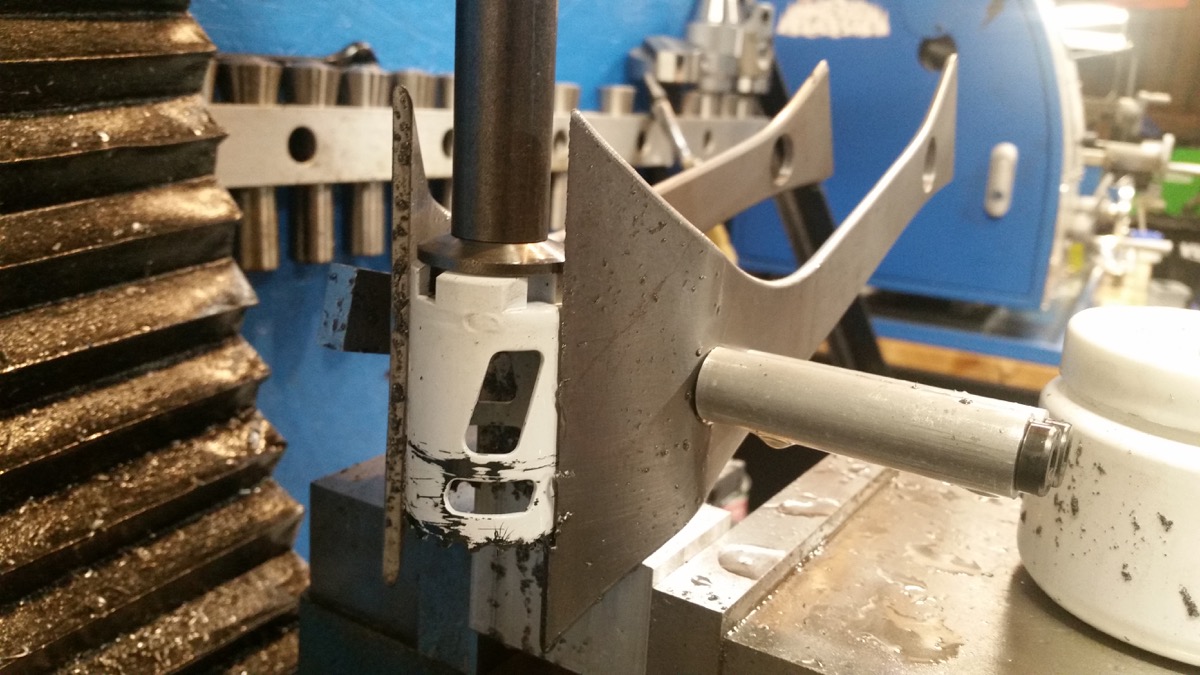

Let’s start with the drivetrain. By using an idler, Evan seeks to control the anti-squat and minimise pedal kick back. Idlers however can be noisy, have poor efficiency and poor durability. The idler sits just behind the pivot point and this particular one is custom machined with 22 teeth. I asked Evan whether this idler wheel was designed for form or function?

‘It is custom. I designed it myself. I was unhappy with how most high-pivot bikes have a lot of drivetrain noise and drag that comes from the small idlers with inadequate bearings. A 22 tooth idler is the same size as the smallest front chainring used when triple chainrings were standard. The idler being larger than the 16 tooth on the Forbidden and 18 tooth on the Deviate allows it to last longer and run smoother. There is a larger surface area that the chain is in contact with which reduces the concentrated loads on the idler’s surface. The larger diameter also means that the angle change that each chain link has to make as it meshes onto and off of the idler is less meaning less friction. I also use a very big double-row bearing that is more than up to the loads seen from hard pedaling. I did the calculations and actually found that most idlers have bearings that aren’t properly up to the task. They actually get damaged from extreme pedaling forces! One other benefit of the forwards idler position is that it reduces the angle of your chain in the extremes of the cassette. Therefore in your climbing gears and descending gears there is less friction loss from the angle of the chain grinding teeth.‘

‘The links and idler pulley were machined by Dave Mather of Mather Machining. He runs a local machine shop and I am so stoked that he took the time to make my parts! They turned out incredibly good! It is hard to describe how good it felt pressing the bearings into links with such perfect tolerances. I’ve never felt anything as nice in nearly 20 years working as a bike mechanic.‘

Is there any chance you’re going to get your shorts tangled in the idler?!

Where there’s a will there’s a way they say! I haven’t had any issues yet. It’s actually quite slim where the idler is. I have a little chain guide that has been added since taking the glamour shots that also doubles as a chain guard. There’s also a design for a really nice chain guide/guard that goes over the idler, but I haven’t got around to machining it since I’ve been too busy riding instead! You can see the basic chain guide in the riding photos. For a production bike the idler would be integrated into the swingarm in such a way that there would be no possibility of getting anything such as your shorts caught in it. As the bike is now was the simplest way of constructing the swingarm to test the concept. I’ll let you know if I ever get my shorts caught!

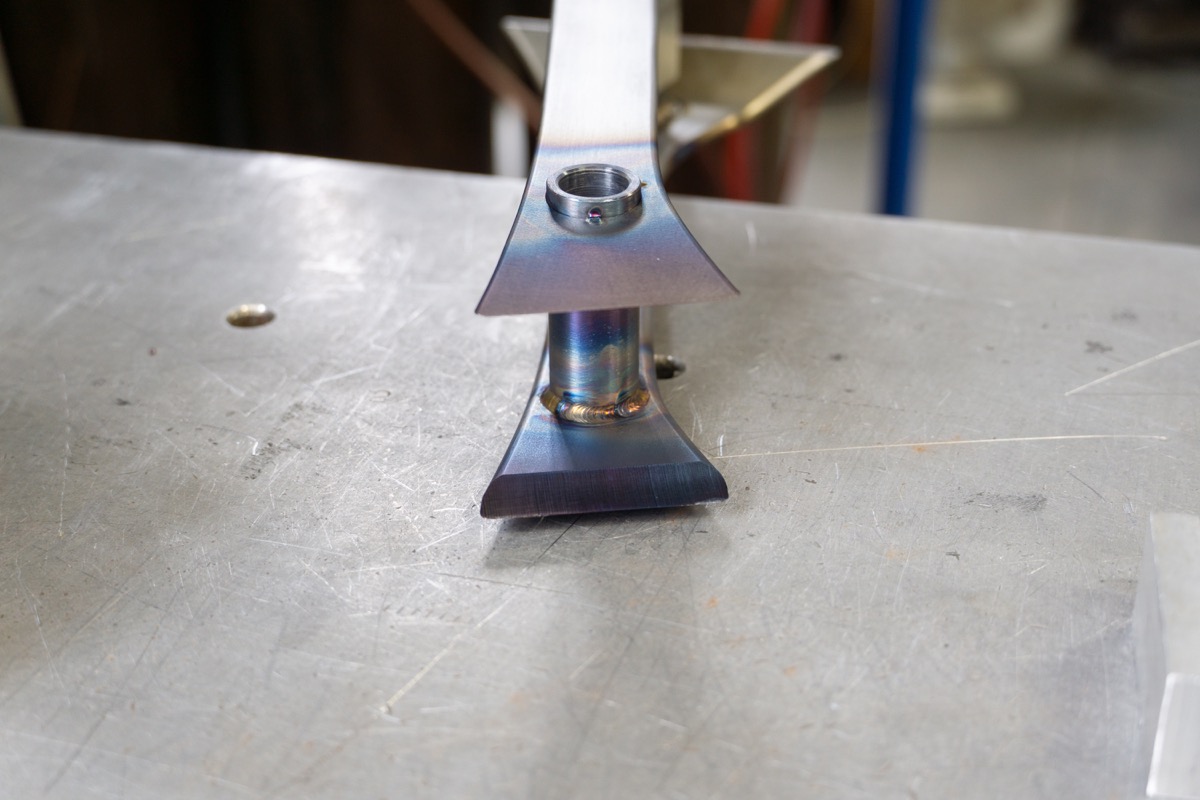

The Shock Mount

The shock mount is set into two huge plates which are welded between the top and down tubes. These plates also host the main pivot. There’s and upper and lower position for the shock – the upper point gives you room for a 164mm shock, which can be paired with a 170mm fork for what Evan calls ‘big hitting bike park or enduro madness’. In the lower position, as set up here, you get 140mm travel. With the near vertical shock and open triangle construction, there’s plenty of room for a bottle.

The Swingarm

Like a dockyard crane, the swingarm reaches ever backwards in a long obtuse triangle, the slim tubing neatly braced with a short crosspiece. The rear brake is mounted onto a plate like a pair of shark’s teeth attached to the upper tube of the swingarm. The chain side gets a long slim strip of protection for from the chain, while cable guides keep the gear cable neatly tucked behind the idler and on top of the lower tube of the swingarm. A bridging piece helps hold the two halves of the swing arm together, just above where it joins the linkage. Maybe in reality it might act as a bit of a mudshelf, but the crisp curves cupping the tyre and seat tube do look pretty. The overall effect is quite elegant, despite the bracing and steam punk look of the drivetrain. If it weren’t for the fact that there are rather a lot of finger trapping options, the temptation to tickle your fingers down its length would surely be strong. Maybe if Evan promised to hold it really still we’d still risk it.

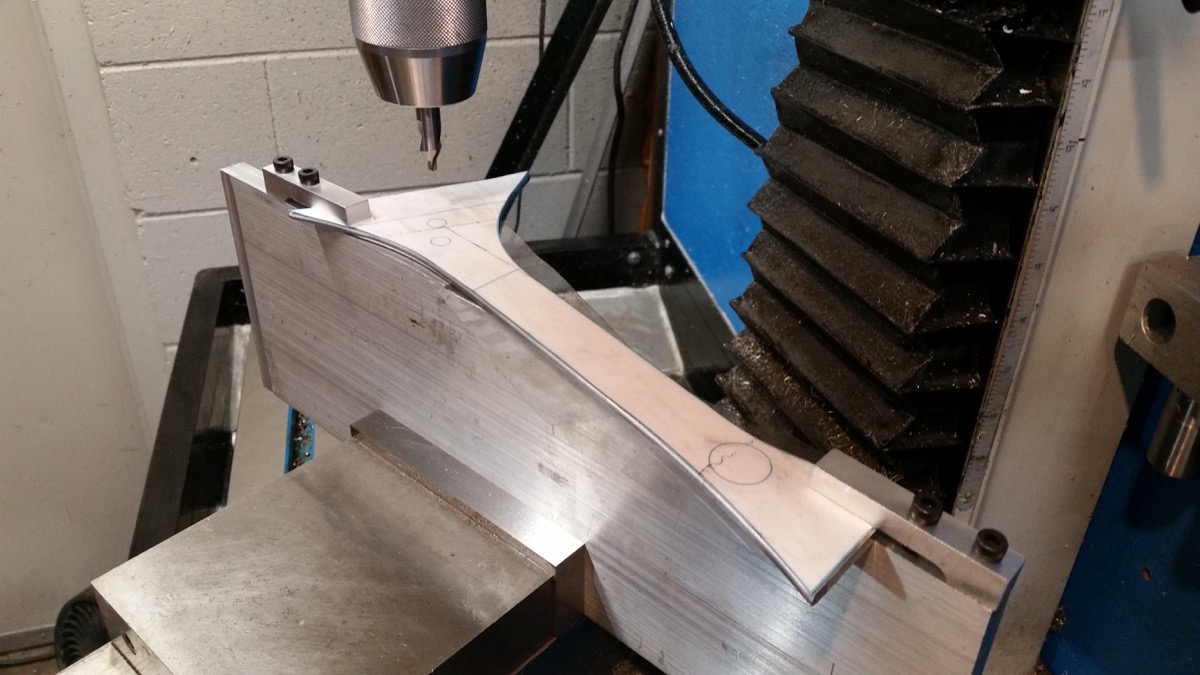

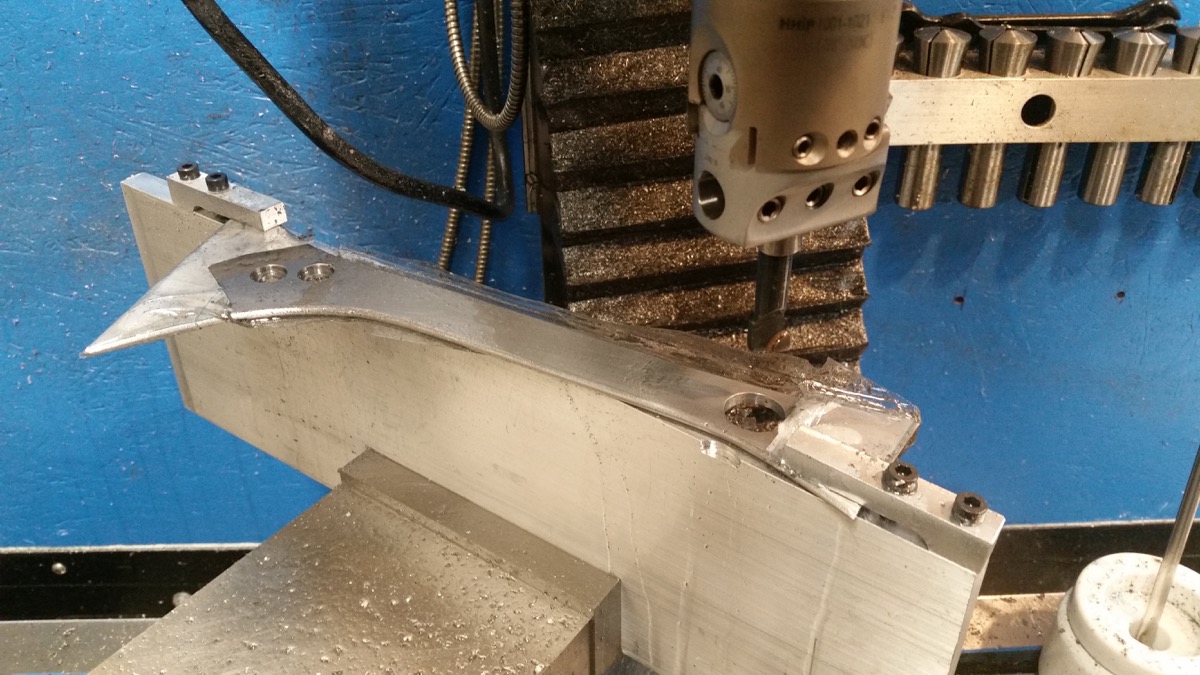

The Frame

As you can see from the construction images, the quality of the mitres is excellent. Incredibly neat and so accurately fitting together before any tacks or welds are added. Just look at how the shock mount sits against the frame. Those mitres are filed finer than a manicure at Harvey Nichols.

Extra Evan hidden content for subscribers only is here – but you need to join us and log in to read it.

It’s a class job on the build – beautiful mitres. Who did it?

‘I did all the mitering myself and fabricated all of the bearing housings, pivot hardware, concentric bottom bracket shell, concentric bottom bracket axle, head tube gusset, shock to main pivot struts, and swingarm brace all by hand and on a manual mill and lathe. The uprights connecting the main pivot to the shock mounts took 5 days in total. They started as 4mm thick steel plate which I laid templates on top of and cut out using a jigsaw and a handful of blades. Then finished with a flap sander, files and emery cloth. Getting the precise bends required was difficult and machining the shock mount and pivot holes was even more difficult. I don’t really want to build those parts again, but they were necessary to have the frame be strong under hard bottom-out forces. Without them the frame would most likely bend!‘

‘All the welding was done by John Caletti of Caletti Cycles. He’s a local frame builder who specializes in high-end custom titanium and steel frames and he is a wizard with a welding torch! There’s no way I would have trusted the bike if I had welded it myself!‘

Draw your eyes away from all the distracting moving parts, and you’ll notice there’s a neat little brace between the heat tube and down tube. There’s something very pleasing about how that fits just so in there.

You’ll notice a sleeve on the seat tube – Evan explains:

‘It is a Paragon Machine Works seat tube sleeve welded to a 1-3/8″ diameter .035″ wall tube This effectively shims the thin walled tube down to 31.6mm to fit a dropper post. This is a common part used for custom frame builders. It saves 220 grams of weight out of the seat tube compared to using a straight wall tube of the same outer diameter that fits a 31.6mm dropper on the inside.‘

As yet there’s no head badge, just raw naked steel. It won’t stay that way for ever, but right now the branding is still a secret, and Evan’s baby is nameless: ‘The bike itself doesn’t have a name yet, but I do have a potential brand name that I really like! I just can’t share it yet for trademark reasons.’

Do you need a moment? Go on, take one. Maybe open a window.

The Geometry

Let’s cool off with a bit of counting and numbers. For this final piece of data, it’s the geometry and weight. Evan is 177cm (5′ 9-1/2″) tall, and obviously he’s designed the bike to fit him (though I’d just like to point out that is the same height as me, so if this needs testing I suppose I could take one for the team…). With a reach of 480mm, it’s in the realm of modern geometry without being wild. A 64 degree head angle is on the slack end of things – matching the Privateer 161 – and the seat tube is steep-ish with an effective angle of 77.9 degrees.

The frame weighs 12.5 pounds including idler, rear axle, seat clamp, all bearings and pivot hardware, and Float X2 rear shock. Evans says:

‘Butted tubing could drop the weight a bit, and maybe certain things here and there could be trimmed down a bit more if needed. Since it is a prototype and the first bike I’ve ever built the extra weight is fine since it should make the frame hold up better. As a complete build including pedals, OneUp EDC tool, spare tube, water bottle cage and pump it’s right at 39 lbs. If you ditch all the tools and spares about 38 lbs. There are no light-weight parts, no carbon. It could be a couple pounds lighter with a fancy expensive build and some smaller brakes, but I like it how it is!‘

Extra Evan hidden content for subscribers only is here – but you need to join us and log in to read it.

What kind of price are you aiming for?

That’s a ways out since this is a “proof-of-concept” prototype. The eventual production bike will most likely be aluminum, a tremendous amount lighter, and made entirely in the USA in small batches. I want to aim to have it be competitive with other high-end aluminum frame prices. It may end up costing a little more though since I don’t want to cut any corners on materials and construction as it relates to durability and ease of (and lack of) maintenance. I want to build a bike that is still great to ride 10 years from now, not in a garbage dump in pieces!

Any idea about production time or is it all early days still?

It is still very much early days. The next step is to take what I have learned from this bike and apply it all towards the next prototype. The next one will be aluminum and much closer to what a production bike will be. I do really like the ride and look of steel, but it is difficult to get the weight and stiffness in a competitive range, especially because this bike is a little more complex. Most steel full suspensions are simple single pivots which makes them easier to build lighter.

Would this be the bike for you? The numbers look good, but there’s always a compromise somewhere. We asked Evan what he would say is this bike’s weakest aspect:

Manualing the bike is a little more difficult at first. Mostly because the balance point is further back than normal. I most likely will shorten the chainstays further on the next one since they don’t need to be as long as a normal bike to have nice real-world stability when riding. Unlike a normal bike with a mostly forwards axle path, when you shift your weight back to manual this bike and compress the rear suspension, the chainstay length increases slightly. Other than that, I am really happy with the geometry. It feels spot on, but I may try 5mm longer reach on the next one for even more stability at speed. That’s it.

And of course, we can’t just stroke it and gaze at it (well, actually, we could, but it deserves to be ridden). So how should we ride it to get the best out of it and make it shine?

‘Stay more centered on the bike and let it do most of the hard work in the rough, because it can. Also take whatever understanding of limits of speed and comfort you are used to and throw them out the window! This bike can handle such greater speeds cornering and in the rough than anything else I’ve ridden before. So much so, that I am having to relearn what is possible. The speed is that much higher!’

Beautiful fabrication on the frame. There seem to be quite a few proponents of high pivot, idler bikes in the small batch world of mtbs now. Question is; will the mass market ever jump on board with the kooky aesthetic?

Droooool!!! That looks incredible. And you can fit a reasonable sized water bottle!

That idler gear looks like it may cause some ‘interesting’ longer baggies interface problems.

Lovely work there.

@Sandwich you haven’t seen the extra hidden content then?

Is there supposed to be a link where it says ‘Extra hidden content is here’ ?

I think your hidden content is possibly ‘extra super hidden’ 🙂

You guys sure it uses a 164mm shock? That seems a little short, especially given Fox doesn’t offer the X2 in that eye to eye length.

@Hannah After that idler has done it’s work there won’t be much hidden content left! (-:

If you’re a paid up member and logged in you’ll automatically see the extra content – extra words from Evan.

Really reminds me of a Brooklyn Machine Works SR6, https://m.vitalmtb.com/community/stevecb78,33028/setup,28836

I like it.

@slimshady The bike uses a 230mm x 65mm stroke shock to get 164mm of rear wheel travel. Not a 164mm length shock! It also has a position to fit a 210mm x 55mm stroke shock to get 140mm of rear wheel travel. Hope this answers your question!

@Duncan Brooklyn Machine Works and the SR6 were ahead of their time in many ways. I did see that exact bike when coming up with ideas for mine. It does have some similarities like the large idler pulley and steel construction. Kinematics, layout, and geometry are the real big differences with my bike. My idler pulley is also not concentric to the main pivot which is how it achieves the unique anti-squat.